Summary

D/KX 82188 Petty Officer Walter Watson, HMS Mahratta was lost at sea 25 February 1944, aged 30. He is commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial [1] and Evenwood War Memorial.

Family Details

Walter Watson was born 12 April 1913[2], the son of William and Mary Ann Watson and brother to Fred, William, Mary Ann and Robert. William Watson was a publican, running the Queen’s Head in the Centre, Evenwood. Following William’s death in 1920,[3] Mary continued to run the pub which was the family home and where Walter grew up.[4] Mary Watson eventually moved to 53 Gordon Lane, Ramshaw.

In 1940, Walter married Betty Hackworthy [5] and was the father of a daughter, Beryl.[6] Betty was pregnant at the time of Walter’s death so he never knew his daughter. Betty Watson lived at Keyham, Devonport. [7]

Military Service

The Service Record of D/KX 82188 Petty Officer Walter Watson has not been researched and the following details are from various sources. He served aboard HMS Mahratta.

The Battle of the Atlantic

“The Battle of the Atlantic was the dominating factor all through the war. Never for one moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea or in the air depended ultimately on its outcome”

Winston Churchill

On the high seas, the Battle of the Atlantic pitted the Royal Navy against Hitler’s U-boats. Britain as an island nation and fighting alone against Nazi aggression relied on goods from the USA, both military equipment and food. Merchant shipping needed to cross the North Atlantic. Lessons learnt in WW1 meant that the convoy system of merchant vessels with a Royal Navy escort was the most effective means of delivering goods to Britain. Inevitably, there were heavy casualties amongst the Merchant Fleet and Royal Navy as the U-boats and other ships of the Kriegsmarine (German Navy) and the Lufftwaffe (German Air Force) held the upper hand during the early years of the struggle. When the Soviet Union joined the Allies, convoys headed for ports at Archangel and Murmansk in Northern Russia, through the north Atlantic between Iceland and Norway into the Arctic Circle.

The Arctic Convoys

The Arctic convoys of World War II travelled from the United Kingdom and the United States to the northern ports of the Soviet Union, Archangel and Murmansk. There were 78 convoys between August 1941 and May 1945. There were two gaps with no sailings between July and September 1942 and March and November 1943. About 1400 merchant ships delivered vital supplies to the Soviet Union under the Lend-Lease program, escorted by ships of the Royal Navy, Royal Canadian Navy, and the U.S. Navy. Eighty-five merchant vessels and 16 Royal Navy warships (2 cruisers, 6 destroyers and 8 other escort ships) were lost. The Nazi German Kriegsmarine lost a number of vessels including 1 battlecruiser, 3 destroyers and at least 30 U-boats as well as a large number of aircraft.

The second series of convoys, JW (outbound) and RA (homebound) ran from December 1942 until the end of the war, though with two major interruptions in the summer of 1943 and again in the summer of 1944. The convoys ran from Iceland (usually off Hvalfjörður) north of Jan Mayen Island to Archangel when the ice permitted in the summer months, shifting south as the pack ice increased and terminating at Murmansk. After September 1942 they assembled and sailed from Loch Ewe in Scotland. The route was around occupied Norway to the Soviet ports and was particularly dangerous due to the proximity of German air, submarine and surface forces. The likelihood of severe weather, the frequency of fog, the strong currents and the mixing of cold and warm waters (which made ASDIC use difficult) plus drift ice were only some of the deadly hardships which had to be endured. Other hazards were the alternation between the difficulties of navigating and maintaining convoy cohesion in constant darkness on top of which they were under daily attack. All in all, the Arctic Convoys voyages were extremely dangerous.

20 February 1944: JW57 convoy left Loch Ewe, 42 ships strong. The auxiliary carrier HMS Chaser joined the escort. In addition to the through and ocean escorts, a support group from the Western Approaches was also to accompany it as far as Bear Island.

22 February: the ocean escort joined the convoy off the Faeroes.[8]

“As had been demonstrated in the Atlantic, this combination of close escort, support group and air escort was too much altogether for the submarines. Their efforts were completely disorganised and not once did they penetrate to they convoy, while an escorting Catalina caught and sank one of them and the Chaser’s Swordfish harried them, making repeated attacks with their new rocket projectiles, which were a great improvement on the old depth charges.”

In the black of the night, heavy swell, blinding snow flurries, U-990 executed a brilliant attack and 2 torpedoes hit the destroyer HMS Mahratta. HMS Impulse quickly came to her aid. She was still afloat and in touch by radio and manoeuvring round came bow to stern alongside her forecastle. Mahratta rolled steeply over to port and capsized. [9]

“By the time Impulsive reached the spot only struggling figures, saturated and blinded by oil fuel and rapidly becoming paralysed by the cold were to be seen. As Impulsive drifted down to them, scrambling nets over the side, few had the strength left to grasp them, fewer still were able to hoist themselves up the stiffly frozen rope. Volunteers from the Impulse’s crew at the bottom of the nets, repeatedly doused into the icy water as the ship rolled, did what they could to help them. But, alas, the total number saved was but 17 out of a company of more than 200.”

42 ships delivered thousands of tons of vital war equipment to Russia but the Kola Run had again taken its toll in human lives.

HMS Mahratta (G23)

M-Class Destroyer ordered from Scotts Engineering & Shipbuilder, Greenock 7 July 1939 under the 1939 Programme and intended to be named HMS Marksman. She was laid down 21 January 1940 but the incomplete structure was blown off the slipway during an air raid on the Clyde in May 1941 and the structure was dismantled to allow transfer to an alternative site. The ship was launched 28 July 1943 as HMS Mahratta following a decision in July 1942 to introduce this name in recognition of the financial support given by India to the war effort. In February 1942 this ship was adopted by the civil community of Walsall, Staffordshire after a successful Warship Week National Savings campaign.

HMS Mahratta, under the command of Lt. Cdr. Eric Arthur Forbes Drought, D.S.C. R.N., was escorting convoy JW-57 when she was struck by a Gnat torpedo from U-990 and sunk on 25 Feb 1944. The destroyer sank within minutes at position 71º12’N, 13º30’E. Only 16 men survived out of a crew of 236.

U- Boat 990

It was a type VIIC, ordered 25 May 1941, laid down 17 October 1942 at the Blohm & Voss shipyard, Hamburg. She was launched 16 June 1943, commissioned into service 28 July 1943 under the command of Kapitänleutnant Hubert Nordheimer from that date to 25 May 1944 when she sank in North Sea west of Bodö, in position 65.05N, 07.28W, by depth charges from a British Liberator aircraft (Squadron 59/S). There were 20 dead and 33 survivors. U-990 took part in Wolfpack operations as follows:

Werwolf (28 Jan 1944 – 27 Feb 1944)

Orkan (5 Mar 1944 – 10 Mar 1944)

Hammer (10 Mar 1944 – 26 Mar 1944)

Blitz (2 Apr 1944 – 4 Apr 1944)

U-990 successes – 1 warship success for a total of 1,920 tons sunk, HMS Mahratta in the first Wolfpack operation.

Kapitänleutnant Hubert Nordheimer was born 3 Feb. 1917 at Mirschkowitz, Silesia and died 2 May 1996 aged 80.

The Plymouth Naval Memorial

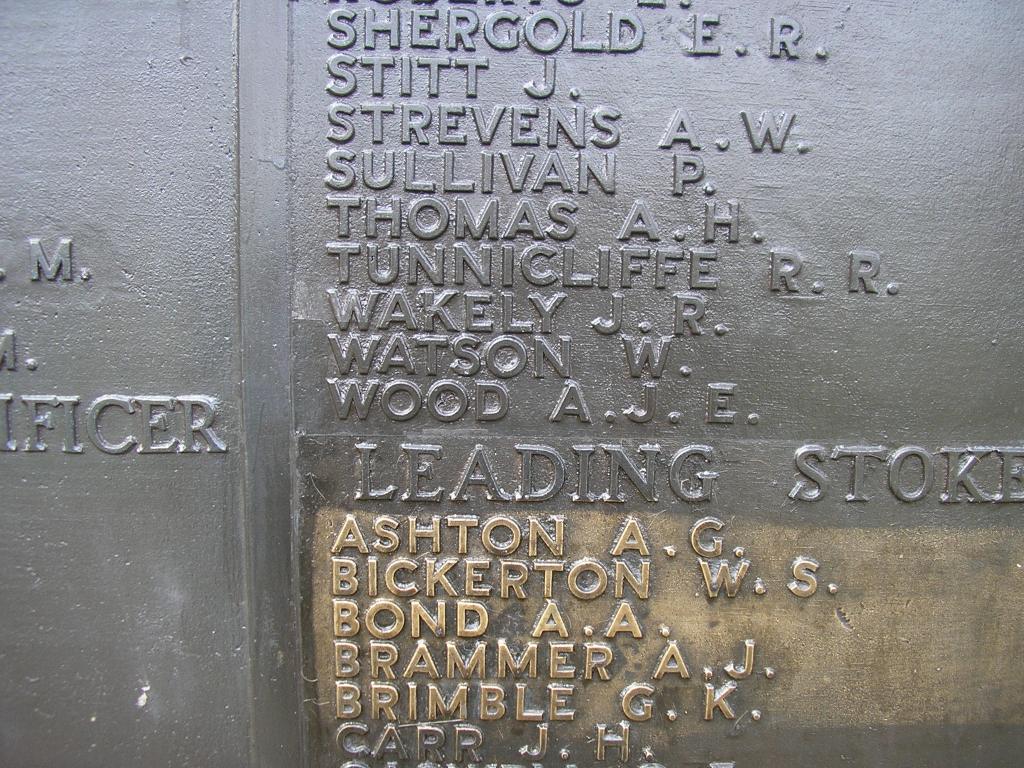

D/KX 82188 Petty Officer Walter Watson is commemorated at Panel 89 Column 2, the Plymouth Naval Memorial. After the Great War, the 3 manning ports at Chatham, Plymouth and Portsmouth were selected to house the memorials to those lost at sea. There are 15,933 sailors of the Second World War commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial.

The Northern Echo 6 May 2005 Jack Humble

“I thought: why do I have to die so young?”

Temperatures rarely rose higher than 10 below freezing and the cold was almost as big a danger as the U-boats. Nick Morrison speaks to a veteran of the Arctic convoys about the night his ship was torpedoed and how a miracle saved his life.

It was 9pm and Jack Humble was in his bunk. It was another 3 hours until his next watch and he was taking a much needed rest. In his hammock he could escape the otherwise constant cold and the endless cycle of chipping ice from the ship’s deck. It was February 25, 1944 and they were just south of Bear Island inside the Arctic Circle.

Then the torpedo struck.

There was panic. Seamen stampeded for the deck. But what Jack – who had turned 18 just a month earlier – did next almost certainly saved his life.

All he was wearing was his underwear, nowhere near enough to stave off the cold of the Arctic Ocean. So he started to put on as many clothes as he could find, his sea socks, sea boots, his gloves and his mitts.

But as he went down the passageway to make his way on deck, a second torpedo struck.

“It was terrible really, the explosion was out of this world.” He recalls. “The ship was shaking. People in front of me were shouting “We can’t get out.”

The door to the stairs had been blocked by debris from the blast. The sailors were trapped and seemed doomed to go down with the sinking ship. But after what seemed an age, the debris cleared and they rushed out on deck. The scene that greeted them was far from reassuring.

“People were throwing themselves overboard because the ship was sinking.” says Jack, 79, who still lives in Durham, the city of his birth. “They were shouting for their wives and their mothers. It was terrible.”

He saw a friend – Alec Jones. Alec asked for his gloves, so Jack gave him his mitts, which Alec put on his feet. But they knew their prospects were as bleak as that stormy Arctic night. Their ship, HMS Mahratta was at the back of the convoy and it would be some time before they could be picked up by another ship. Jumping into the sea seemed to offer only another way to death.

Jack and Alec tried to release the rafts which lined the deck of the Mahratta but they were frozen solid. They linked arms bur before they could jump a huge wave came over the side of the listing ship and took them into the sea. Jack never saw Alec again.

“I was getting sucked under with the ship. I remember getting pushed round and round under the water. But, in a little bit of luck I suppose, I came to the top and managed to swim away from the ship. Everybody around me was dead. I tried speaking to people. Nobody answered, I couldn’t find anybody alive.” He says, struggling to contain the emotion. “They had been in the water longer than I had. I just thought that was the end.”

He was covered in oil from the ship. It was in his eyes, making it difficult to see but it may also have helped insulate him from the cold.

Then he heard a voice. Another sailor was alive. The voice shouted that there was a ship in the distance. Jack, through his oil-smeared eyes, could barely make out an outline but they started to swim towards it. The other sailor had been in the water for longer and before they were within hailing distance, could go no further. Jack never knew his name, “He saved me but he didn’t save himself.” He says. “I remember thinking, “I don’t know why I have to die so young”. I don’t remember much after that.”

But he swam on, the freezing water penetrating the layers of clothing. Tiring and weakening with every stroke. As he neared the ship he finally made out the shape of a destroyer, HMS Impulsive.

The crew saw him in the water and threw him a line. Jack started to climb but his fingers were numb from the cold and slippery from the oil and he had gone only a few feet when he fell back into the water. Life expectancy was an average of 5 minutes. Jack had been swimming for about 20. He knew then end was close.

But if it was the atrocious conditions that drew him close to death, it was those same conditions which came to his aid.

“I was being thrown about. The next thing I knew, a wave took me up the side of the ship to the level of the deck. They grabbed me by the hair and pulled me in.”

Jack was carried below, his rescuers rubbing his hands and feet to try and get his circulation going. He was laid on a table. The crew of the Impulsive brought another survivor of the Mahratta, a petty officer and put him beside Jack. He died while the crew worked on him.

It was the next day before Jack awoke again. He was told 17 survivors had been pulled from the sea. The Mahratta had a crew of 246, “I lost all my pals, really,” he whispers.

Jack remained on board the Impulsive which continued on its way, escorting ships laden with military equipment to bolster the Russian war effort. When they reached Russia, the 17 survivors were taken to hospital. Two were in a bad way and were put in a separate room. One day they were gone. Jack never knew what happened to them.

He was taken back to England on aircraft carrier HMS Chaser. It had been only his second Arctic convoy, just a few months after he enlisted as a 17 year old cycling from his Durham home to the recruiting office, Jubilee School, City Road, Newcastle. He had wanted to join the RAF but his age meant he could only be an apprentice. In the Navy he could be a gunner. He chose the Navy.

On his return to Britain, he decided the Navy was no longer for him. He joined the Army and was recruited into the Parachute Regiment.

In 1945, he was dropped into Denmark, mopping up the retreating Germans. After the war ended, he served in Palestine for 2 years before he was discharged.

Twenty years after the war, he went to Stockton in search of Alec Jones’ house in Ware Street, Norton. He hoped to find relatives of the man who had linked arms with him as they were swept into the water. The street had been pulled down.

A few years earlier he had been contacted by one of the other survivors of the Mahratta, a Corporal Fred Hill, then serving at Catterick. Cpl. Hill wrote to him then came up to visit but they lost touch a few years later. He has never heard from any of the other survivors.

Jack never joined a veteran’s association. He rarely talks about what happened and has never joined the campaign of the Arctic convoys which claimed 3,000 lives, though he supports it. But this does not mean what happened is of little importance to this widowed grandfather.

“It is always there. You never forget it.” He says. “In those days we didn’t have counselling – we went back and we got on with our job. I don’t think I shed a tear. It is an awful thing to say but I don’t think I shed a tear over it. You just accepted this is war, this is what happens.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Jean Green, Bishop Auckland, Co. Durham

The late Jack Humble, Nevilles Cross, Co. Durham

REFERENCES

[1] Commonwealth War Graves Commission

[2] UK British Army & Navy Birth, Marriage & Death Records 1730-1960 & England & Wales Birth Index 1837-1915 Vol.10a p.555 1913Q2 Auckland

[3] England & Wales Death Index 1916-2007 Vol.10a p.238 1920Q3 Auckland

[4] 1911 census

[5] England & Wales Marriage Index 1916-2005 Vol.5b p.977 1940Q1 Plymouth

[6] England & Wales Birth Index 1916-2007 Vol.5b p.346 1944Q4 Plympton

[7] “Walter married a girl from Plymouth and brought her to meet the family on his leave at Christmas 1943. That same Christmas, Walter took my father (Robert) to one side and told him confidentially that on his return to base he was being deployed on Russian Convoys and if there was any bad news, he had directed the R.N. to inform my father first who would then have to break it to my grandmother. Sadly, that tragic news came 2 months later, in February…To add to the family sadness, Walter was unaware on his return to duty in February that his young wife (Betty) was pregnant and she gave birth to a daughter (Beryl) in October, a child he would never know.” Jean Green, Walter Watson’s niece, her father being Robert, Walter’s older brother.

[8] “The Kola Run: A Record of Arctic Convoys 1941-1945” I. Campbell & D. Macintyre 1958

[9] “The Kola Run: A Record of Arctic Convoys 1941-1945” I. Campbell & D. Macintyre 1958