The road system in England had shown little improvement since the Roman times.

Below: Binchester, Bishop Auckland: the Roman road revealed.

As the industrial revolution took hold, commerce developed and communication between cities, towns and villages increased, there was an urgent need to improve the antiquated road system. A scheme for improvement of a particular route would be put together by businessmen because it was in their best interests. Any such scheme required an Act of Parliament to sanction it. Briefly, named land owners and businessmen would propose improvements and were allowed to levy charges (tolls) on those people and goods that passed over the road. Gates, then known as “turnpikes” would be located at particular locations to catch the traffic and men were employed to gather tolls. In time, this system was developed so that individuals (or families) had to bid to become a toll keeper. Their living would depend upon how much they collected in tolls. In theory, part of the money raised would be used for road improvements.

The most important roads covered by Acts of Parliament in our area were:

- 1745 The Post Road: Borough Bridge to Durham via Northallerton, Croft Bridge and Darlington. 52 miles via Topcliffe, Thirske, Northallerton, Croft, Darlington, Aycliffe village, Ferryhill and Croxdale. There were 7 toll gates at Topcliffe, Newsham, Lovesome Hill, Entercommon, Croft Bridge, Harrowgate Hill/Aycliffe village & Sunderland Bridge [Croxdale]

- 1747 Stockton to Barnard Castle 21 miles and 6 toll gates at Elton, Sadberge, Haughton, Baydale, Gainford and Whorlton

- 1748 Sunderland Bridge to Bowes passing by a toll gate at Evenwood Gate

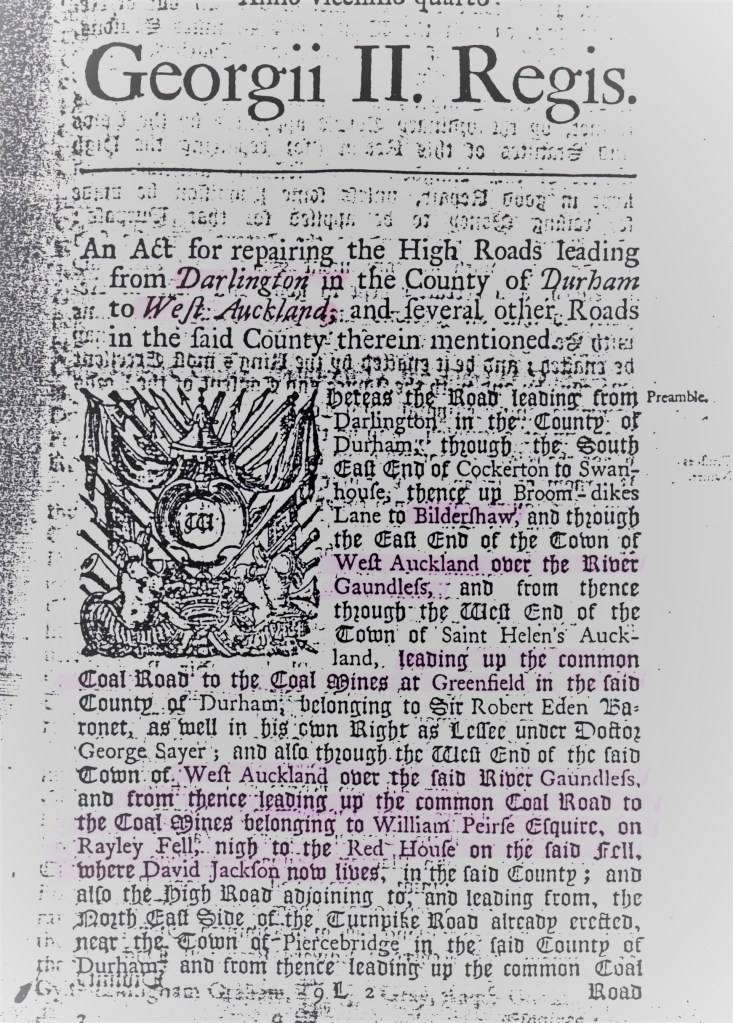

- 1751 The “Coal Road”: Darlington to West Auckland, total length 21 miles via Cockerton, Swan House, Broom Dikes Lane, Bildershaw, West Auckland, St. Helen’s Auckland to the coal mines at Greenfield and to the coal mines at Rayley Fell belonging to William Pierse esq. near the Red House [Etherley] and to Piercebridge via Royal Oak, Leggs Cross, Denton cross roads. There were 5 toll gates at Royal Oak, Leggs Cross, Denton Cross Roads, Houghton Bank and Burtree Gate.

- 1761 Staindrop to Gately Moor [Gilling West] North Yorkshire

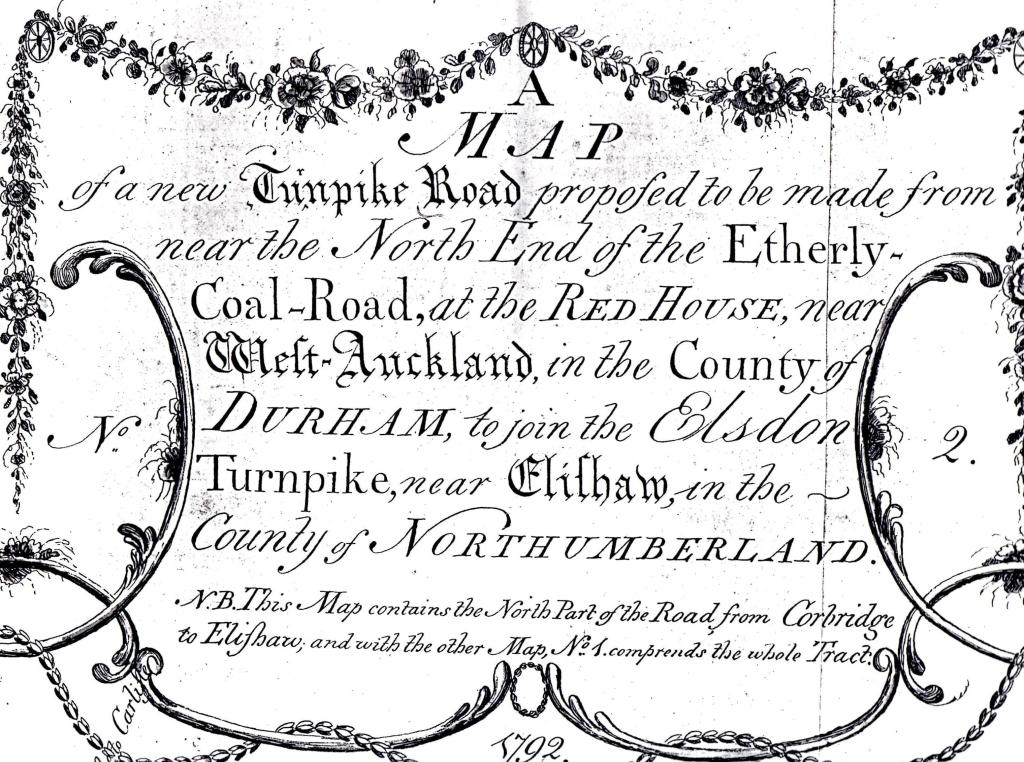

- 1792 Red House [Etherley] to Elilham, Northumberland

- 1792 Red House [Etherley] to Eggleston

- 1795 Staindrop to Cockerton Bridge, 12 miles long and had 3 toll gates at Coniscliffe Moor, Ingleton and Killerby.

By 1810 there were 19 trusts controlling 400 miles of road in County Durham and by 1835, there were 1135 trusts controlling 23,000 miles of road in England & Wales.

Below: 2 illustrations of a “romantic style” which show travel by coach – they depict the hazards of travel.

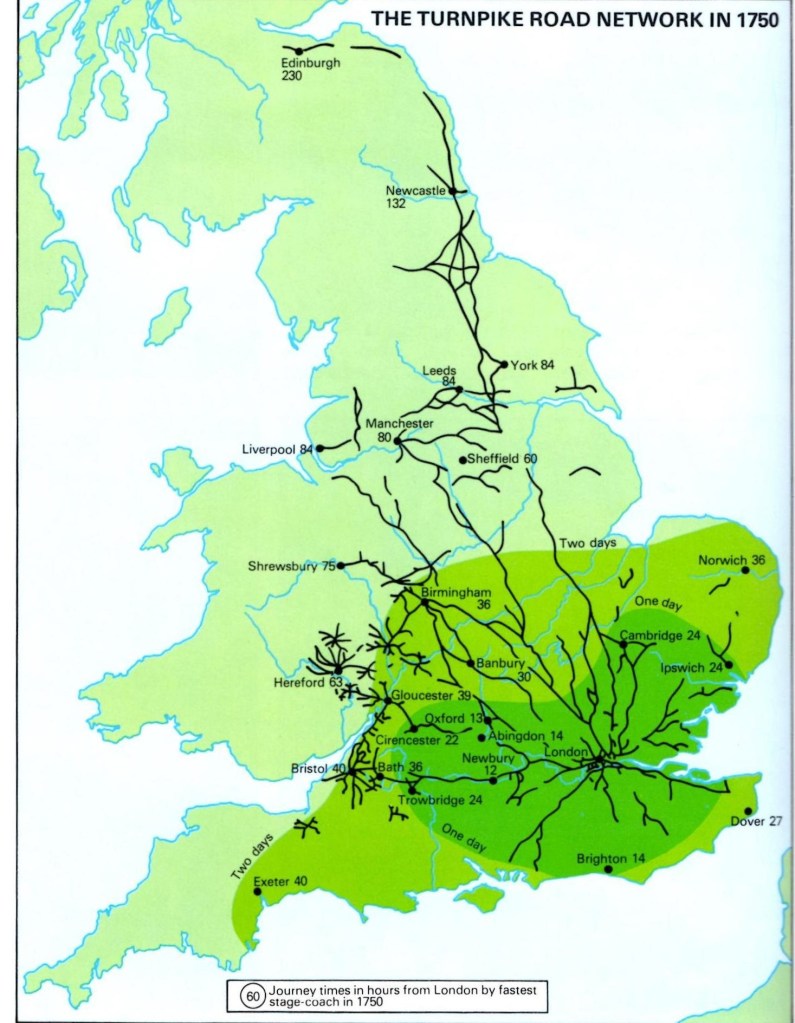

Below, 1750, a map to show the TURNPIKE ROAD Network

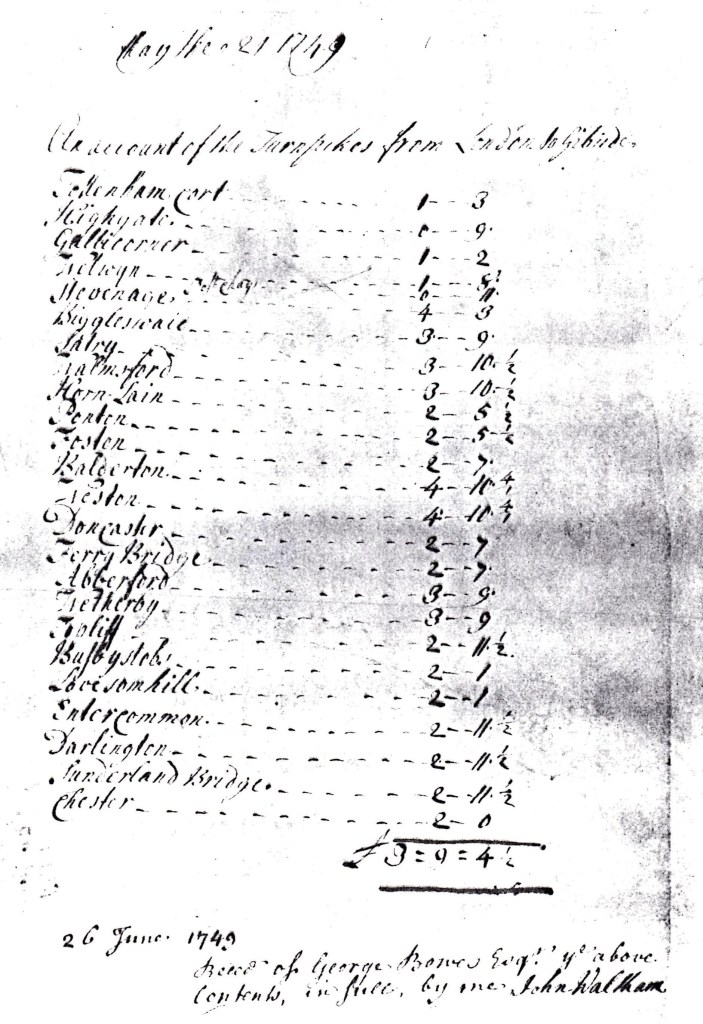

Below, 1749, an account of the tolls paid by George Bowes on his trip from Tottenham Court, London to his home near Chester-le-Street at Gibside.

George Bowes would have travelled by horse and carriage. The route was from Tottenham Court via Highgate, the next place cannot be deciphered, Welwyn, Stevenage, Biggleswade, Sandy, Tempsford, Horn Lain ( a modern name cannot be traced), Ponton (south of Grantham), Balderton (south of Newark), Weston, Doncaster, Ferrybridge, Abberford, Wetherby, Topcliffe, Busby Stoop, Lovesome Hill, Entercommon (the modern day name has not been traced), Darlington, Sunderland Bridge to Chester (le-Street). This road was commonly called, “The Great North Road” and the part through North Yorkshire was called, “The Post Road”. Later, much of the route would become the A1. In total, there were 24 toll gates and the total cost was £3…. 9 shillings… 4 and a half pennies. This would be about £900 in today’s money.

Around Huntingdon, there were 2 alternative routes but modern road improvements has obliterated most of the evidence. However, at Ermine Street (named after a Roman road) at Great Stukeley, to the north of Huntingdon, a milestone still exists – a rare example. London is 61 miles and Huntingdon 2 miles.

Below: Great Stukeley milestone

In many areas of England, there was some competition in the movement of goods – canals were extremely important. However, there was not much interest in canals in the north east counties of Durham and Northumberland. As can be seen in the map above, there were few turnpike roads in the north of County Durham. There were no canals. The reason was that tramways were preferred. The most valuable commodity was, of course, coal and tramways were constructed, usually fed by gravity, from collieries to the River Tyne or River Wear. From there, the coal could be transported by sea to London and other destinations.

One such tramway system was developed by the above named George Bowes and transported coal from his Marley Hill Colliery in north west Durham to staithes on the river Tyne at Jarrow where it was exported to London or used to produce coke, iron and steel to build ships by his business partner, Charles Palmer. It was built by George Stephenson in 1826 and later extended westwards to include other collieries at Byermoor, Burnopfield and Dipton. This tramway was notable for use of hauling engines. The industrial remains of this tramway is now known as the Bowes Railway, situated at Springwell, near Gateshead and is open to the public. Below are some photographs to show parts of the incline and railway.

Below: The incline looking towards the river Tyne in its heyday

Below: The view today

Below: A chauldron, the truck used for loaded coal

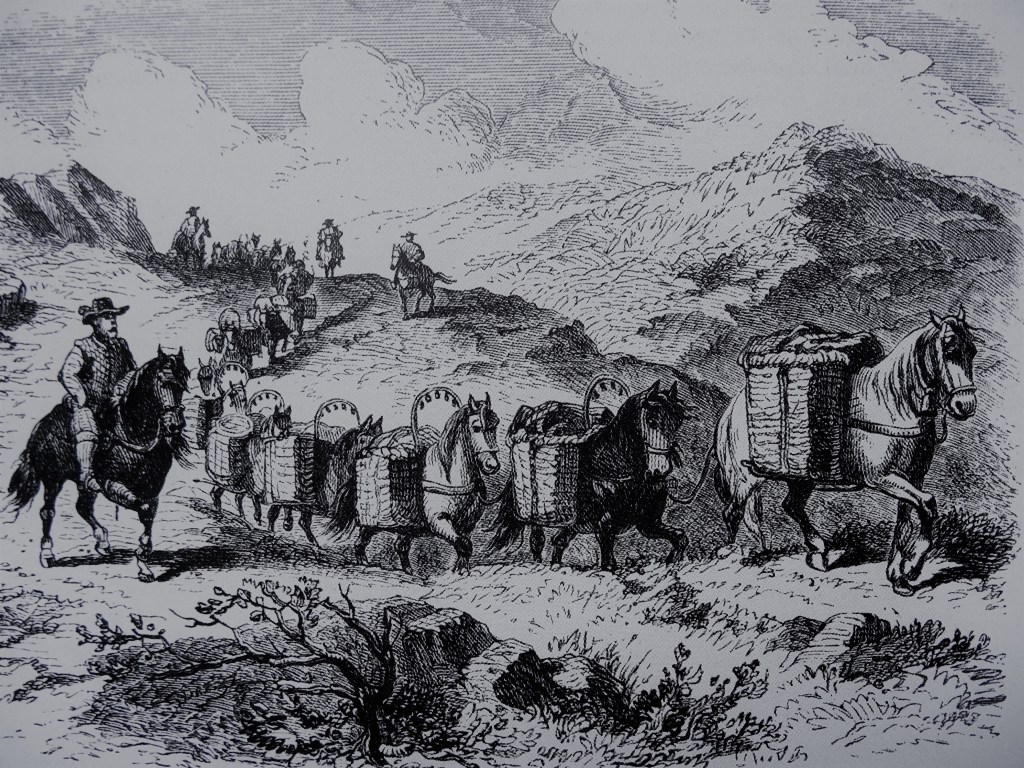

By contrast to north Durham, the coal reserves in the south of the county were not developed on the same scale. The coal which needed to be transported, was done so using pack horses and carts. The destination for the coal was relatively local – Darlington and Richmond in North Yorkshire. Some may have gone to Durham for the use of the Bishop.

Below: An illustration to show a team of pack horses.

As a result, the turnpike road system was more developed in the south of the county. The”Coal Road” was one of the most important turnpike roads, which connected the West Auckland area to Darlington – now the road is the A68. This turnpike road was required, to cart coal from the pits at Greenfield for Sir Robert Eden and Rayley Fell for William Pierse esquire to Darlington, Richmond and elsewhere.

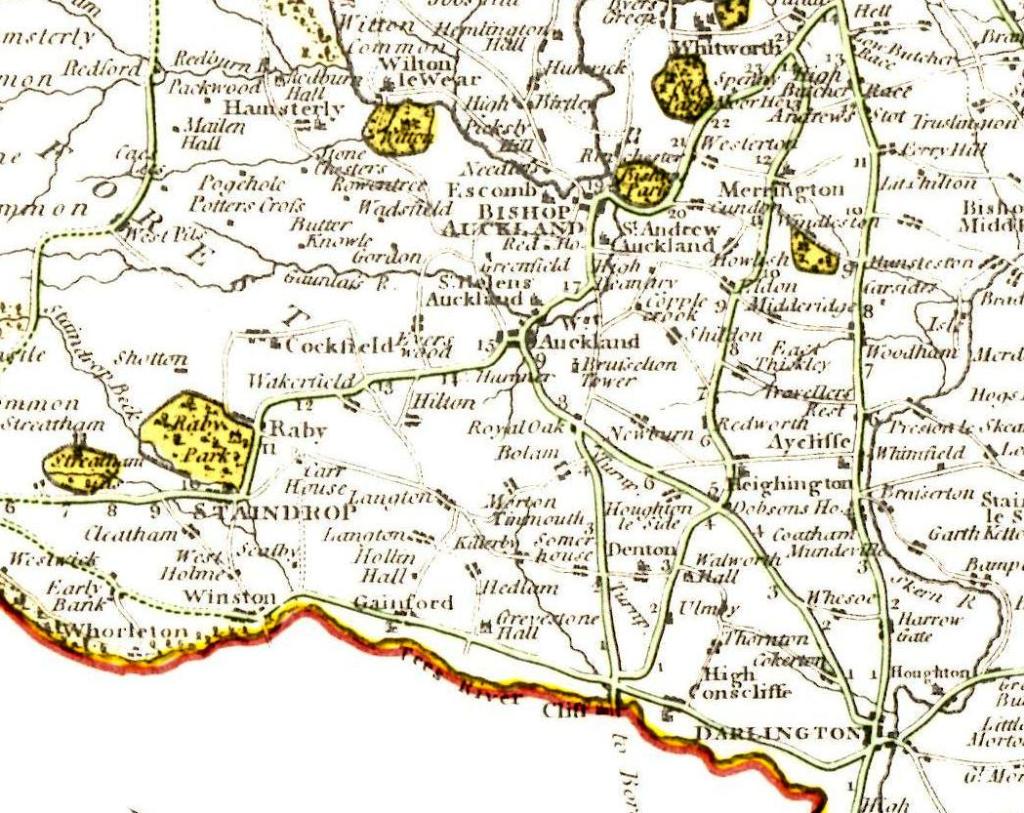

1750: South Durham, sketch map to show the Turnpike Roads

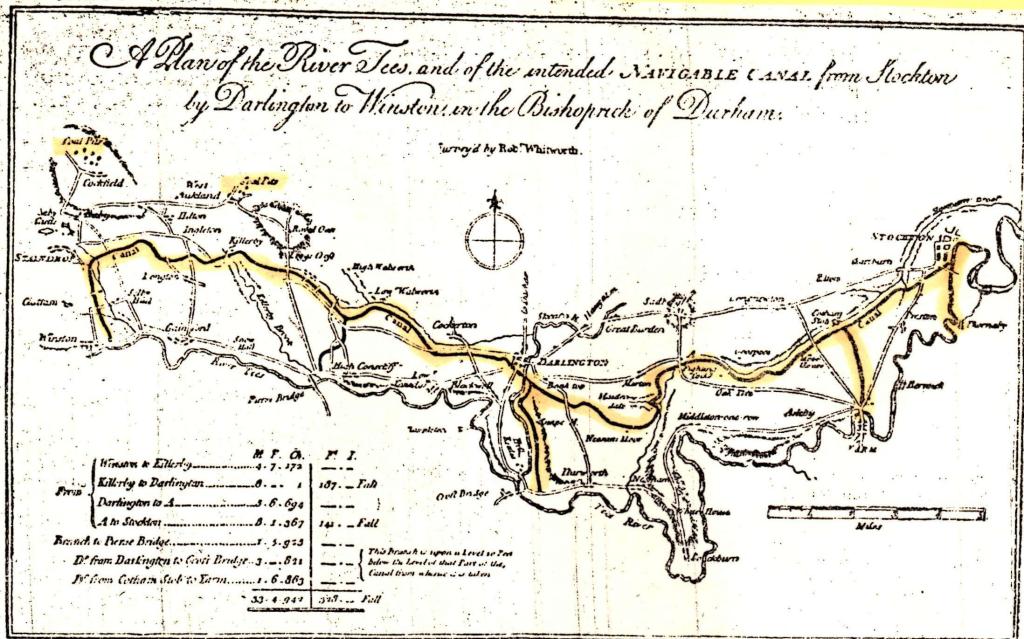

1770: One canal scheme was surveyed in 1768 was relevant to our area. Coal from the largely unexploited Auckland Coalfield was proposed to be transported to the port at Stockton. It failed to gain support. The proposed route was from Stockton via Darlington to Winston and followed a line south of the higher land from Brussleton to Cockfield to Woodland. It came close to Denton, Killerby, Ingleton and Staindrop.

Below, 1769 plan showing the route of the proposed canal, Stockton to Winston.

The turnpike roads continued to earn money for their sponsors and promoters – coal being the main merchandise.

Below: 1751, the front page of the Act of Parliament authorising the “Coal Road”.

Below, 1787 Carey’s Map, a detail to show the route of turnpike roads in south Durham.

1792 – a new turnpike road was deemed necessary to connect coal mines to the north of West Auckland area and as such the route from Etherley (Red House) to Corbridge was planned.

Below 1792 – The legend to the map for the new Turnpike Road

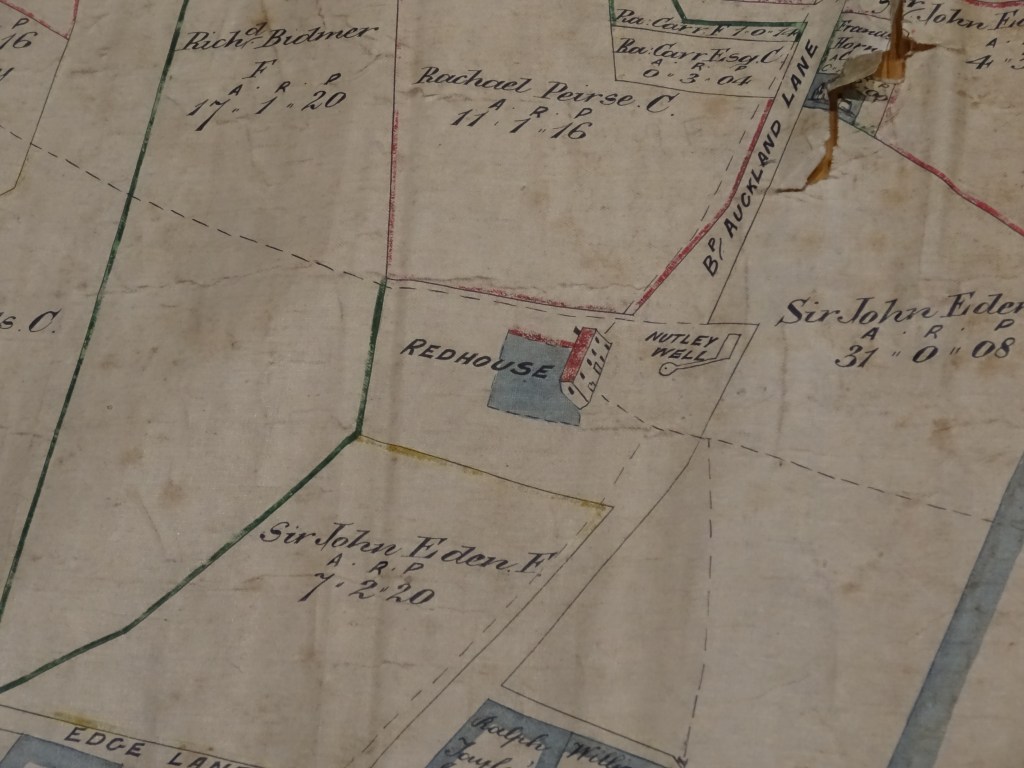

Where was the Red House? Below, this 1765 plan shows the Red House at Etherley on Bishop Auckland Lane, north of Edge Lane which was the road from Toft Hill to Woodland (then known as the Edge).

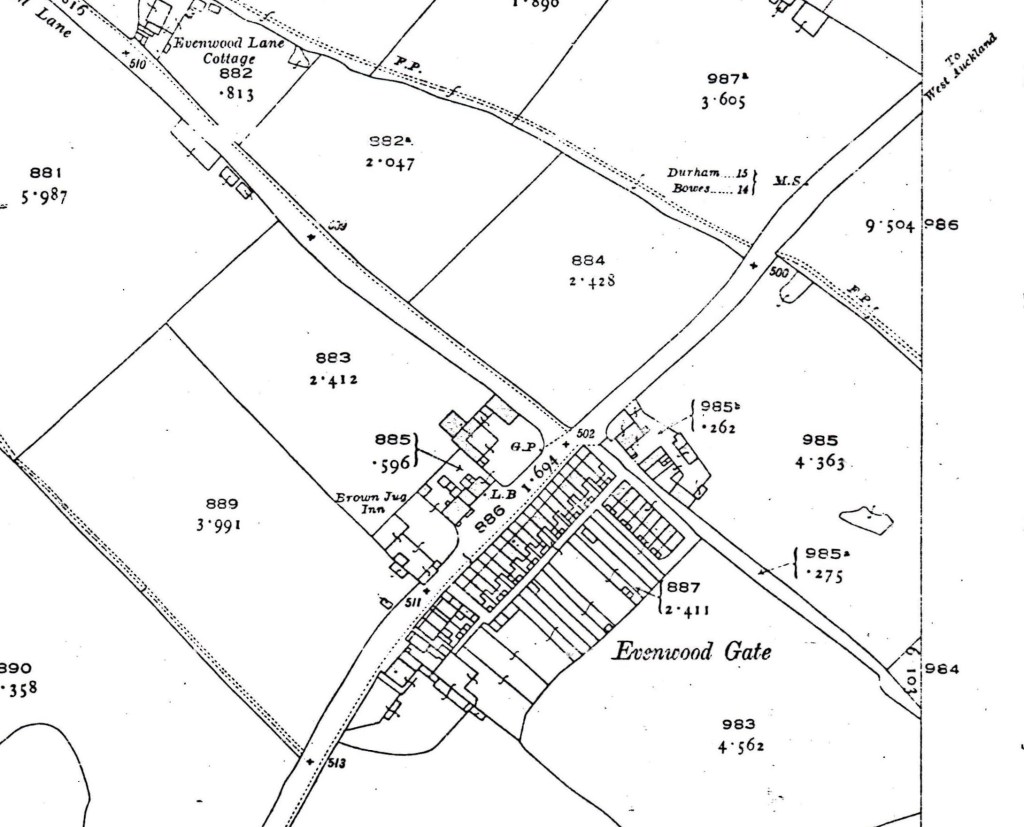

1859, the map below shows the turnpike road passing Evenwood Gate – the gate was on the turnpike road, required to prevent passage of carts so they could be stopped and charges collected.

Below: A later plan shows the initials, M.S., to the east of Evenwood Gate. This refers to the milestone located near to the road. It informed road users that Durham was 15 miles and Bowes 14 miles.

Below, May 2017, a photo of the milestone. Looking at the plan above, it is probably on the wrong side of the road.

The Milestone is cataloged on the Listed Buildings Register. The description is:

“Milestone. Probably late C18 with C19 OS bench mark. Sandstone. Irregular tapered block, c. one metre long, with inscription “Durham 15 miles” in one of 2 smooth faces; bench mark below. Lying in grass at time of survey NZ 1639124378″

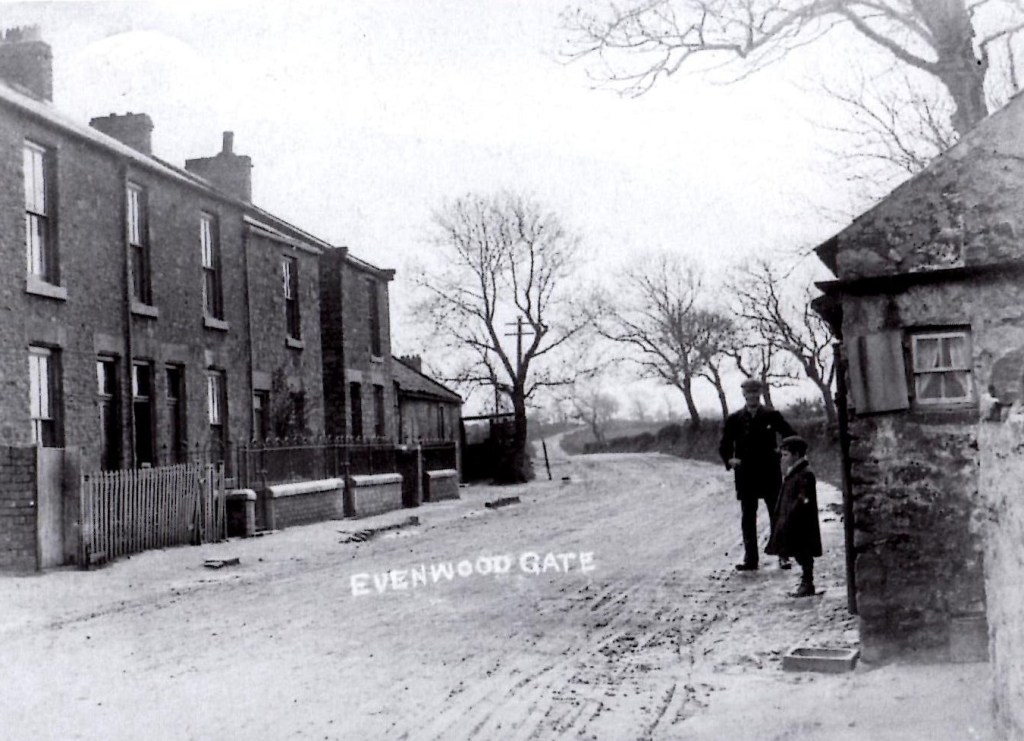

Below, The gate (toll) house at Evenwood Gate on the right hand side of the photo

The view in 2017

ADMINISTARTION WAS LEGALISED BY THE 1773 GENERAL TURNPIKE ACT

Income raised from charges was re-invested into the repair of the roads. The trustees were responsible for the system and employed:

- a toll keeper who was responsible for the collection of tolls and

- a surveyor to be responsible for the upkeep of the road.

The toll gates were offered at auction with a reserve price set by the Trustees. The highest bidder won the right to work the toll gate and be employed as the toll keeper. Any money over and above the auction price was the profit of the toll keeper. A house by the gate was provided by the Trustees rent free.

In 1811, the surveyor to the Coal Road, Darlington to West Auckland earned £60

Trustees

In 1784, Robert Shafto, John Tempest, Sir John Eden, Thomas & Andrew Bowes, Sir Walter Blackett, all influential people in the County being land and coal owners were among the list of trustees for the Coal Road. Also included were members of the Pierse family from Low Worsall, North Yorkshire, who owned coal mines at Rayley Fell, west of Toft Hill. The coal from Rayley Fell was sent to areas of south east Durham and north Yorkshire so this road would be of immense benefit to the Pierse family.

Charges

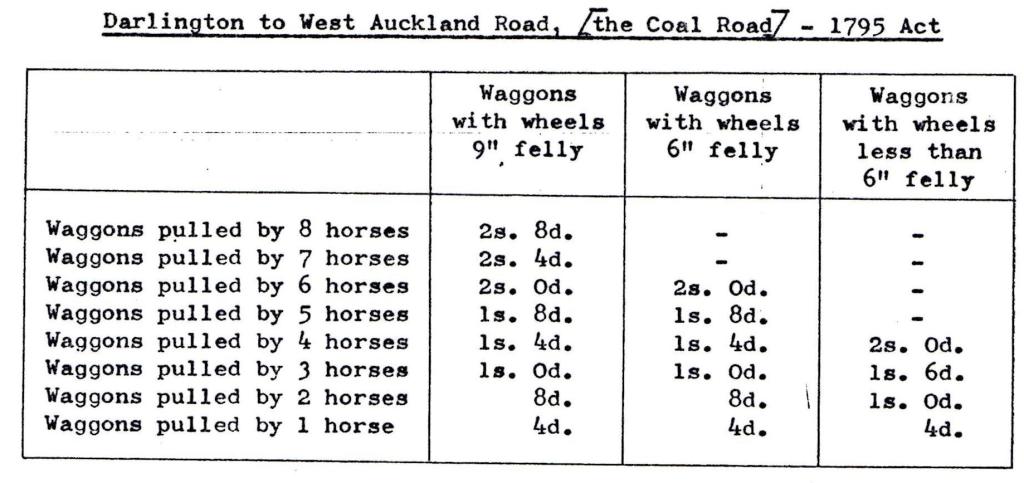

The charging system was complex, being based on the type of cargo, the size of waggon, the width of its wheels and the number of horses or draught animals. Traffic consisting of coal, cinders and lime was charged less than other goods. The coal owners were trustees therefore charged favourable rates for their goods. Some tolls were double on Sundays to discourage traffic.

Below: 1795, The table shows tolls – fees for use of the Turnpike Roads

In 1818, the Burtree Gate profit was estimated at £50 pa when the gate was let for £360.

Traffic

In 1789 the total receipts from the Royal Oak, Leggs Cross, Denton Lane, Houghton Bank & Burtree Lane gates was £960. In 1825, the total was £1,870 with the Royal Oak gate bringing in the highest income – £396 in 1789 and £790 in 1825. In 1820 the income at Royal Oak was £980 but it reduced to £355 in 1834, £100 in 1849 and by 1871 the income fallen to £70.

In 1818, in one year 60,000 waggons carrying coal passed through the Burtree Gate and a similar number of waggons passed through Piercebridge. It is likely that most of this traffic came from the pits at Greenfield, north of West Auckland and Rayley Fell, west of Toft Hill. The Norwood colliery, north east of Evenwood was working by 1796 so no doubt contributed to this traffic.

Decline

From 1840 with the development of railways, the decline of goods traffic was evident. In 1864, Parliament encouraged the winding up of trusts and there is no evidence that gates were auctioned after 1871. The turnpike trusts had had their day. It was now the age of steam and the railways.