Summary

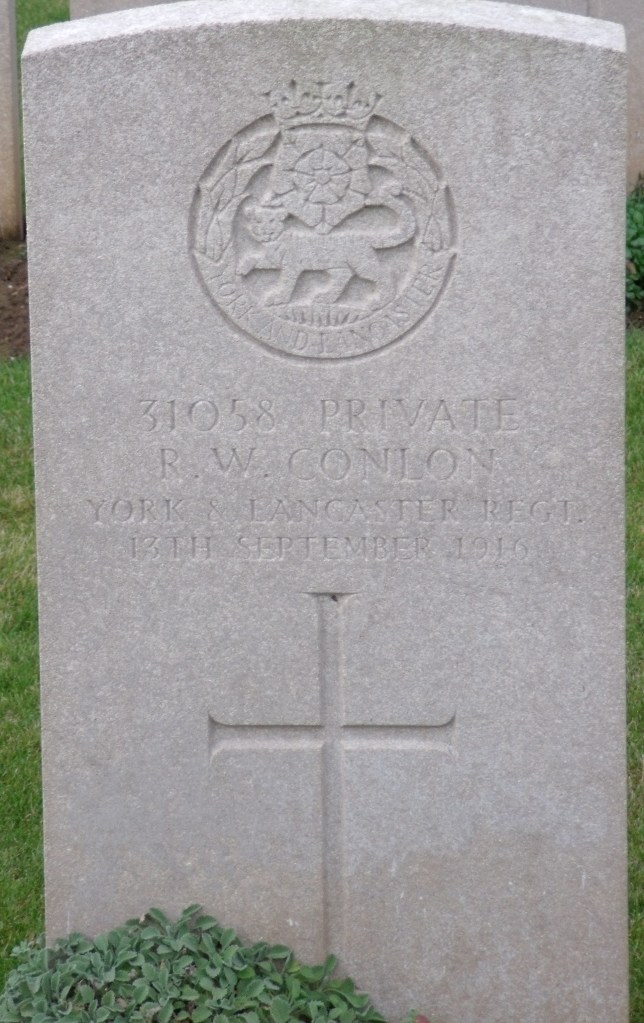

31058 Private Robert William Conlon, 2nd Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment died of wounds 13 September 1916 and he is buried at Peronne Road Cemetery, Maricourt.[1] He was 36 years old and is commemorated on the Evenwood War Memorial.

Family Details

Robert Conlon was born 1883 [2] but his immediate family has not been traced. In 1911 Robert Conlon lodged with William and Phoebe Morley at Lands Bank.[3] In 1916, his next of kin was his cousin Mrs. Dorothy Race. Robert lived with her at High Lands. No immediate family was recorded on his attestation form. [4]

William Morley’s brother was 243094 Private Walter Morley, 4/Yorkshire Regiment who was killed in action 15 May 1918.[5] He is buried at the ANZAC Cemetery, Sailly-sur-la-Lys, France and also commemorated on Evenwood War Memorial.

Service Details

23 February 1916: Robert William Conlon attested. He worked as a timber feller.[6]

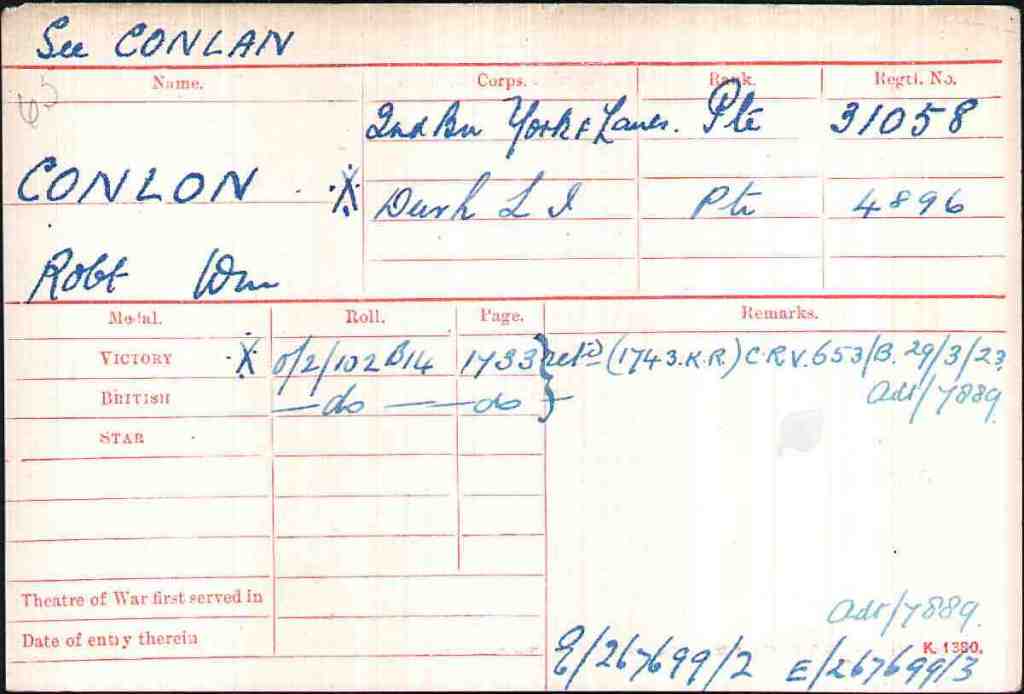

27 March 1916: He undertook a medical examination when his declared age was 36 years 5 days.[7] He was 5’4” tall and declared fit for general service. He joined the Durham Light Infantry and was given the regimental number 4896. [8]

6 September 1916: Private R.W. Conlon was transferred to 2/York & Lancaster Regiment [9] and was given the regimental number 31058. The date he entered France has not been traced.

The 2/Yorks. & Lancs. Regiment came under the orders of 16th Brigade, 6th Division together with the following battalions: [10]

- 1st Buffs

- 8th the Bedfords

- 1st Leicesters (left Nov.1915)

- 5th Loyal North Lancs (left June 1915)

- 1st Kings Shropshire Light Infantry

- 16th Brigade Machine Gun Company formed February 1916 left March 1918

- 16th Trench Mortar Battery formed April 1916

The Battle of the Somme: 1 July – 18 November 1916: an overview [11]

The Battle of the Somme was viewed as a breakthrough battle, as a means of getting through the formidable German trench lines and into a war of movement and decision. Political considerations and the demands of the French High Command influenced the timing of the battle. They demanded British diversionary action to occupy the German Army to relieve the hard pressed French troops at Verdun, to the south.

General Sir Douglas Haig, appointed Commander-in-Chief in December 1915, was responsible for the overall conduct of British Army operations in France and Belgium. This action was to be the British Army’s first major offensive on the Western Front in 1916 and it was entrusted to General Rawlinson’s Fourth Army to deliver the resounding victory. The British Army included thousands of citizen volunteers, keen to take part in what was expected to be a great victory.

The main line of assault ran nearly 14 miles from Maricourt in the south to Serre to the north, with a diversionary attack at Gommecourt 2 miles further to the north. The first objective was to establish a new advanced line on the Montauban to Pozieres Ridge.

The first day 1st July 1916 was preceded by a week long artillery bombardment of the German positions. Just prior to zero-hour, the storm of British shells increased and merged with huge mine explosions to herald the infantry attack. At 7.30am on a clear midsummer’s morning the British Infantry emerged from their trenches and advanced in extended lines at a slow steady pace over the grassy expanse of a No Man’s Land. They were met with a hail of machine gun fire and rifle fire from the surviving German defenders. Accurate German artillery barrages smashed into the infantry in No Man’s Land and the crowded assembly trenches – the British suffered enormous casualties:

- Officers killed 993

- Other Ranks killed: 18,247

- Total Killed: 19,240

- Total casualties (killed, wounded and missing): 57,470

In popular imagination, the title, “Battle of the Somme” has become a byword for military disaster. In the calamitous opening 24 hours the British Army suffered its highest number of casualties in a single day. The loss of great numbers of men from the same towns and villages had a profound impact on those at home. The first day was an abject failure and the following weeks and months of conflict assumed the nature of wearing-down warfare, a war of attrition, by the end of which both the attackers and defenders were totally exhausted.

The Battle of the Somme can be broken down into 12 offensive operations:

- Albert: 1 – 13 July

- Bazantin Ridge: 14 – 17 July

- Delville Wood: 15 July – 13 September

- Pozieres Ridge: 15 July – 3 September

- Guillemont: 23 July – 3 September

- Ginchy: 9 September

- Courcelette: 15 – 22 September

- Morval: 25 – 28 September

- Thiepval: 25 – 28 September

- Le Transloy: 1 – 18 October

- Ancre Heights: 1 October – 11 November

- Ancre: 13 – 18 November

Adverse weather conditions i.e. the autumn rains and early winter sleet and snow turned the battlefield into morass of mud. Such intolerable physical conditions helped to bring to an end Allied offensive operations after four and a half months of slaughter. The fighting brought no significant breakthrough. Territorial gain was a strip of land approximately 20 miles wide by 6 miles deep, at enormous cost. British and Commonwealth forces were calculated to have 419,654 casualties (dead, wounded and missing) of which some 131,000 were dead. French casualties amounted to 204,253. German casualties were estimated between 450,000 to 600,000. In the spring of 1917, the German forces fell back to their newly prepared defences, the Hindenburg Line, and there were no further significant engagements in the Somme sector until the Germans mounted their major offensive in March 1918.

An account of the 6th Division

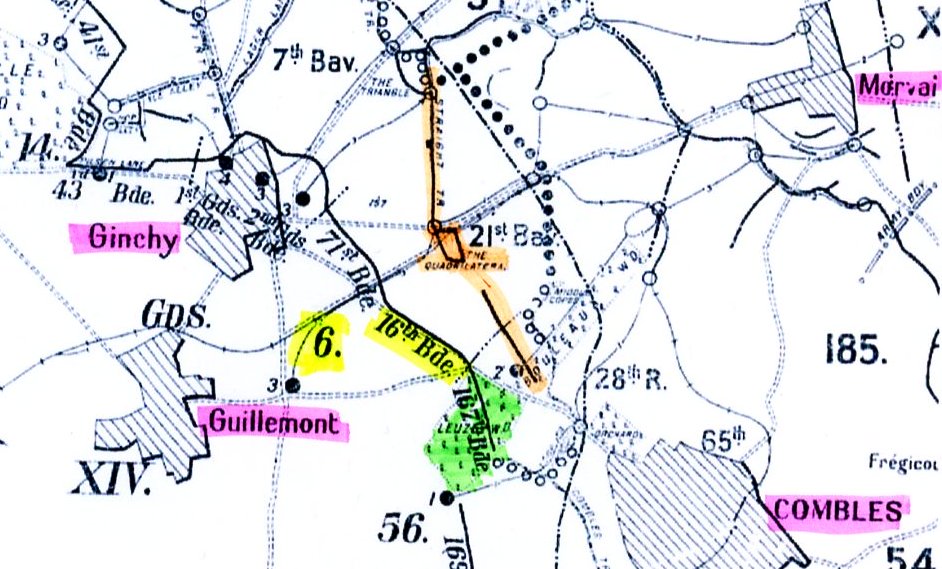

August was spent on the Ancre on the front opposite Beaumont-Hamel. After a short period in reserve the Division was moved between 6 and 8 September to join the XIV Corps Fourth Army. 9 September: a successful attack had captured Ginchy and Leuze Wood but the Germans held the high ground which forms a horseshoe between these 2 points. The trenches followed the shape of the spur and covered access was given to them by a sunken road leading back to the deep valley which runs north from Combles. At the top of the spur was a 4 sided trench called the Quadrilateral, a parallelogram of some 300 x 150 yards. This strong point held up the advance of the Fourth Army and it was the task of the 6th Division to obliterate the horseshoe and straighten the line in preparation for a general attack 15 September.

Attacks by the 56th Division to the south and the Guards to the north reduced the neck of the horseshoe to about 500 yards but the attack could not close it. The situation ion the ground was undefined – the exact positions of the trenches in the Quadrilateral were unknown. Bad weather prevented observation by aircraft and bombardment had obliterated villages, roads and railways.

On the night 11/12 September: the 71st Brigade relieved the Guards and the 16th Brigade relieved part of the 56th Division with orders to attack 13 September and straighten the line by capturing the Quadrilateral.

13 September: Artillery co-operation was weak, observation being difficult thus the northern attack could only advance 500 yards and the southern attack even less. Casualties from enemy artillery and machine gun fire were heavy. A second attack the same day at 6.00pm succeeded in bringing the line to within 250 yards from the Strong Point and joined up with the 16th Brigade.

Preparations were then made to include an attack on the Quadrilateral in the general offensive of 15 September. The objectives were to capture Gueudecourt, Flers, Lesboeufs and Morval. The XIV Corps including the Guards and the 6th Division were detailed to take Lesboeufs and Morval.

The 2nd Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment War Diary has not been consulted therefore the exact nature of its operations during this action remains un-researched. Contrary to the detail provided above, when other units suffered heavily, 2nd Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment casualties were light on the 13 September 1916. Private R.W. Conlon being the battalion’s only fatality that day. He received abdominal wounds and died on the way to the Advance Dressing Station.[12] Later research records that between 13 and 15 September 1916, 2nd Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment lost 35 Other Ranks killed in action or died of wounds. [13]

Private R.W. Conlon was awarded the British War and Victory medals.[14] Mrs. Dorothy Race of High Lands was his next of kin (cousin) and she received his commemorative plaque and scroll and presumably his medals.

Burial

Private R.W. Conlon is buried at grave reference III.C.12 Peronne Road Cemetery, Maricourt, originally known as Maricourt Military Cemetery No.3. It was used until August 1917 and completed after the Armistice by concentrating graves from the battlefields in the immediate neighbourhood and from smaller burial grounds. There are now 1348 First World War burials in the cemetery.[15]

Commemoration

Private R.W. Conlon is commemorated on the Evenwood War Memorial. His name is spelt Conlin.

REFERENCES

[1] Commonwealth War Graves Commission

[2] England & Wales 1837-1915 Vol.10a p.263 Teesdale 1883 Q4

[3] 1911 census

[4] Army Form B.2512

[5] CWGC

[6] Army Form B.2512

[7] Note: his attestation form states 5 months

[8] Medal Roll

[9] Army Form B.103 Casualty Form – Active Service Note: May be 10 September 1916 but much of Private Conlon’s service details are undecipherable. The date he entered France is not known.

[10] http://www.1914-1918.net/yorkslancs.htm

[11] Various sources including “The Somme” Hart and “The First World War” Keegan

[12] Army Form B.103 Casualty Form-Active Service

[13] Officers and Soldiers Died in the Great War

[14] Medal Roll

[15] CWGC