AND OTHER LOCAL BRICK & TILE WORKS

New Moors Pottery[1] was located to the south east of Evenwood Gate, about ¼ mile along the track which leads to New Moors farm. Currently, 2023, the site is occupied by a residence and several outbuildings. The land was subject to a long running planning dispute when a second bungalow, which had been built without the benefit of planning permission, was demolished.

The exact date when the pottery was established has not been traced. It was operational by 1816 and the Ramshay family owned the pottery in 1827. The likelihood is that it was working well before then. There were several families who had an interest in the New Moors Pottery including the Ramshays, the Youngs, the Suttons, the Snowdons, the Thorburns, the Schofields and the Lax family. In the 1860s, members of the Schofield family moved to Penrith to Wetheriggs Pottery and were joined later by others. Together, they forged a good reputation for the pottery and its products. Ralph Lax was the last known potter to work the business in 1901. The pottery closed shortly afterwards, probably in 1902 but definitely before 1911.

The following account will provide details of specific families and information relating to the New Moors Pottery and other brick and tile manufacturing works in the area.

Below: Products believed to be from New Moors Pottery[2]

1783 to 1851, the Ramshay, Young and Sutton Families.

The above families either owned or worked at New Moors Farm and the pottery until an auction held in October 1851 ended the Ramshay family interest. Tax Returns between 1783 and 1824 show that Christopher Ramshay owned and occupied a property at New Moors.[3] The 1783 and 1785 returns identified another property owned by Christopher Ramshay which was occupied by John Young. More information is required to prove that the property occupied by John Young was the pottery. The 1824 Tax Return records that both George and Cicely Ramshay owned and occupied a property each.

1816 Cole’s Map

The map shows clearly the, “Pottery” to the south of “Evenwood Castle.”

1820 Greenwood’s Map

This map indicates, “Tile Sheds” in the location of the pottery shown on the 1816 Cole’s map.

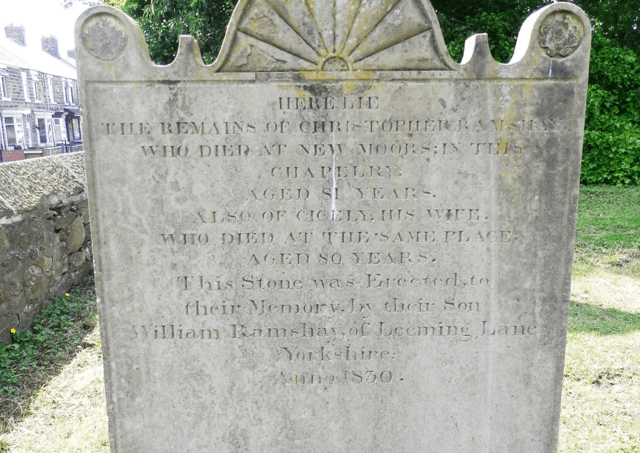

In 1827, Mrs. Ramshay was recorded as the owner of a house and pottery [4] occupied by George Young (junior). In 1828, George Young was recorded as an, “earthenware manufacturer, New Moor” and Cicely Ramshay and Lieutenant George Ramshay R.N. were farmers at New Moor.[5] Commander George Rodney Ramshay (1782-1863) was the son of Christopher and Cecily Ramshay of New Moors Farm, Evenwood Gate. Christopher (1737-1818) and Cicely (1748-1829) are buried at St. Helen’s churchyard.[6] George Ramshay had a 45-year career in the Royal Navy from 1798 to 1844, being rewarded with the rank of “Commander.” In 1822, he married Anna Young and they had 7 children. It is possible that Anna was the daughter of the above mentioned George Young but this has not been verified. Mrs. Cicely Ramshay died in 1829. The pottery changed hands to William Ramshay, presumably George’s older brother, who in 1830, was recorded as having 2 properties. Both were occupied by William Sutton, one was recorded as a house and land and another as a pottery.[7] The 1832 Poll Book records William Ramshay of Leeming, Yorkshire who owned land at Evenwood and George Ramshay of Evenwood who was a freehold property owner. [8] In 1841, William Ramshay was recorded as a, “Brick & Tile maker” living at Leeming, Yorkshire.[9] To date, William Sutton who worked the pottery has not been identified.

Below: The Ramshay headstone in St. Helen’s Churchyard

About 1841 to the 1880s, the Snowdon Family

By 1841 George and Ann Snowdon farmed at New Moors. At this time, George and Cicely Ramshay lived at Evenwood, believed to be a house facing the Green. Those living at New Moors were John Hunter, Sarah Whitfield and John Lowther. They could have been pottery workers or agricultural labourers. James Schofield was recorded as an, “Earthen Ware thrower” and Arthur Metcalfe as a, “Foreman.” [10]

In 1851, George and Ann Snowdon lived at New Moors Pottery together with their 6 children, all born at Evenwood – William bc1833, Elizabeth bc1834, George bc1840, Mary bc1842, John bc1846 and Eleanor bc1848. George Snowdon was described as a, “Brown Ware manufacturer employing 6 labourers and farmer of 113 aces employing 2 men.” John Hunter was a farm labourer and his son John (junior) a, “Potter,” as was Arthur Metcalfe and Peter Denton.[11] Christopher Ramshay owned 4 properties at New Moors, one was occupied by George Snowdon, described as, “House and Land” and his 3 houses were occupied by Arthur Metcalfe, John Hunter and Peter Denton. [12] The Young family also owned land in the area. The executors of George Young owned a house and land at Staindrop Field House occupied by John Thompson senior and junior,[13] a public house at Evenwood Gate,[14] 2 houses and 2 plots of land at Evenwood Gate occupied by George Thompson. Thomas Young owned land at New Moors occupied by George Snowdon. [15] Whether this family was related to Anna Ramshay (nee Young) is unknown.

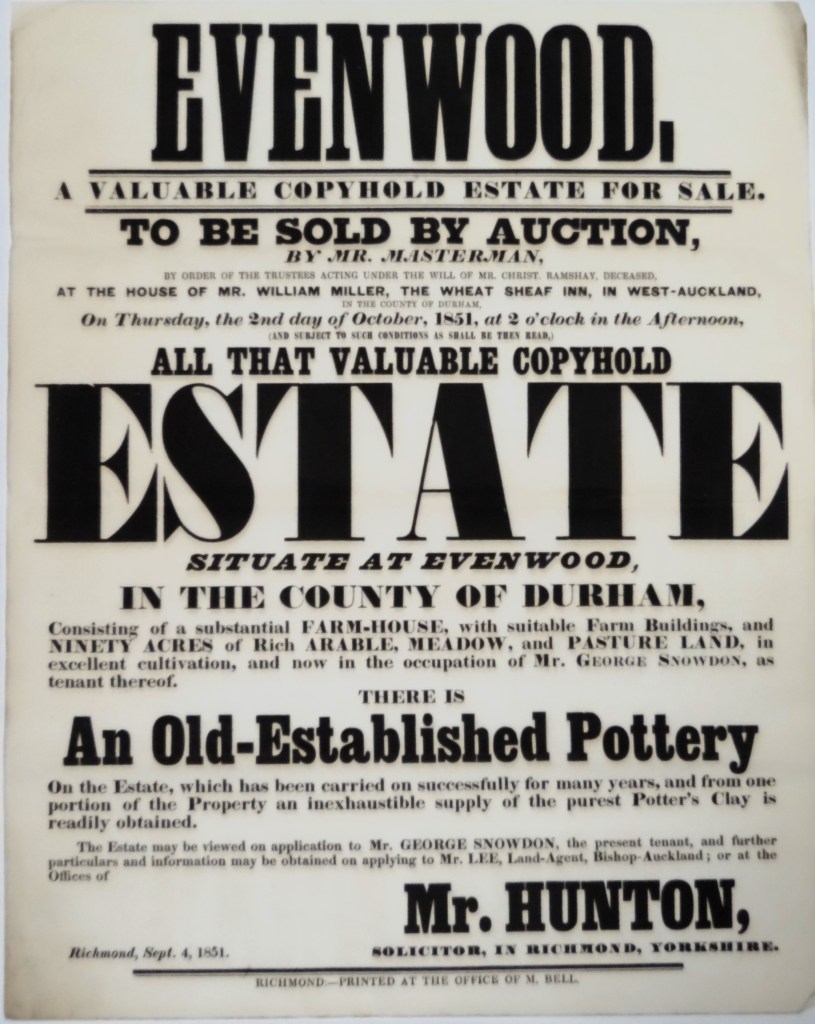

1851: New Moors Auction,

2 October 1851, New Moors Farm consisting 90 acres, the farm house and buildings together with the pottery were put up for auction by the trustees Christopher Ramshay, deceased. George Snowdon occupied the farm as tenant. The description of the pottery states:

“There is an old-established pottery on the Estate, which has been carried on successfully for many years and from one portion of the property an inexhaustible supply of the purest potter’s clay is readily obtained.”

The background to this is that Christopher Ramshay died in 1818 and his wife, Cicely in 1829. It is assumed that the affairs of Christopher, following the death of his wife in 1829, took until 1851 to get settled. It is possible that there were legal disputes or restrictions for it to have taken 20 years or so to organise the auction to settle his affairs. It is assumed that George Snowdon either purchased the estate or, his tenancy was honoured by the new owners, since the Snowdon family retained an interest in the pottery until the 1880s. The Ramshay interest in the pottery was at an end.

Below: The 1851 Auction Poster

Fordyce’s History of Durham of 1857 states:

“At New Moors there is an old established black and brown earthen ware manufacture, the nearby estate provides a plentiful supply of potters’ clay.”

1859 Ordnance Survey Map (1st edition)

This map shows Newmoor Pottery, close to Hummer Beck and a clay pit to the north of New Moors Farm. There were other workings at Hilton Tarn Brick and Tile Works which were northeast of Wackerfield and the road to Hilton. To the south were Whinstone Quarries. Also, there were 3 small coal workings either side of Evenwood Gate and the Sun Inn road (now the A688) which were Park House Colliery,[16] an old coal pit near Park House Cottage and Paddock Mire Colliery.[17] Fireclay is often found within the coal seams and perhaps clay was brought out for use locally.

By 1861, George and Ann Snowdon lived at New Moors Farm worked 260 acres. They also operated the pottery together with employees James B. Thursfield,[18] Thomas Thorburn (overman) and John Hunter.

By 1871, the Snowdon family, in the guise of 62 years old Ann as “head,” still lived at New Moors when she was described as, “Farmer & Earthenware Manufacturer, farm 260 acres employing 3 men and Pottery 2 men, 2 girls.” Thomas Thorburn (Foreman) and John Schofield were recorded as pottery workers. The 1878 edition of, “Ceramic Art of Great Britain” (Llewellyn Jewitt) included the following entry:

“Bishop Auckland: New Moor Pottery, at Evenwood, carried on by Mr. George Snowdon for the manufacture of brown ware.”

By 1881, George and Ann’s son, 35 years old John Snowdon was the occupier of New Moors Farm and described as a, “Farmer of 92 acres employing one labourer, Potter Master employing 4 men & 2 women.” Those employed at the pottery were Thomas Thorburn aged 54, his daughter 25 years old Margaret, his son 19 years old Thomas (junior) and John Schofield, aged 32. At this time, George and Ann Snowdon, now aged 76 and 73 respectively, lived at Oxford Street, Scarborough. Both the farming and pottery interests were now in the hands of their son John.

1877 – 87: New Moors Pottery Sales Ledger [19]

It is assumed that the keeper of the ledger was John Snowdon. It gives a commercial insight, over a 10-year period, to his business which was the manufacturing and shipping a range of earthenware commodities. The contents of the first 2 pages relate to “Ware” and “Carriage” of goods for Mr. N. Bolton, Mr. R. Thompson of Consett, Mr. Thomas Dickinson, Mr. N. Gregg, Mr. Wilson, Dr. Richardson and Mr. William Watson of Hilton. An entry of October 1878 for Her Grace the Dowager Duchess of Northumberland was for dozens of garden pots, thumbpots, large garden pots, hyacinth pots, one large seedpan and two square pans which brought in £6. 1sh. 2d. Other customers for this year included Sussex Milbank of Barningham Park (23½ dozen garden pots), Mr. N. Vart, Major Hodgson of Gainford (16 chimney pots) and Mr. Beckwith of Barnard Castle (30 dozen garden pots and 3 bread plates). The following year, customers included the Executors of the late Charles Pease (150 dozen garden pots and 150 dozen thumbpots) and in 1880, His Grace the Duke of Cleveland (36 washpots, 2 crab picklingpots, 10 flour jars, 2 breadpots, 6 bottles and 1 tray), Mr. Robinson of Stanhope, Mr. J. Pearson of Ingleton, Mr. Robinson Thompson, Mr. Frances Parmley, Mrs. N. Mason, Mr. R. Mountford, Mr. Grundy, Mr. Hall, David Dale Esq., His Grace the Lord Bishop of Durham, Her Grace the Dowager Duchess of Northumberland and Mr. T. Whitfield. Mr. R.S. Bainbridge of Keverston Hall purchased 9 alepots and Messrs. Locke and Blackett of Newcastle ordered 207 dozen leadpots which is understood to be molds for casting lead artefacts. This company was a regular customer, particularly throughout 1886 as was the Middleton Cooperative Society in 1885. Mr. Coates, the Evenwood Station Master ordered 4 pound honey pots, one loaf pot (?), 4 rhubarb pots and 4 dozen garden pots and later in the year, one breadpot, one loafpot, 4 dozen jars, seven rhubarb pots, 5 dozen stands, one pankin,[20] 2 bowls and 3 gardenpots. The Guardians of the Auckland Union purchased one dozen 14” pots. James Harris of Market Place, Barnard Castle (Wholesale and Retail) Grocer, Tea Dealer and Confectioner, dealer in china, glass and earthenware placed orders on a regular basis.

The last entry is in 1877. The ledger confirms that the pottery, under the management of John Snowdon, manufactured a wide range of earthenware products and enjoyed an extensive and loyal clientele.

Below: Selected paged from the Ledger

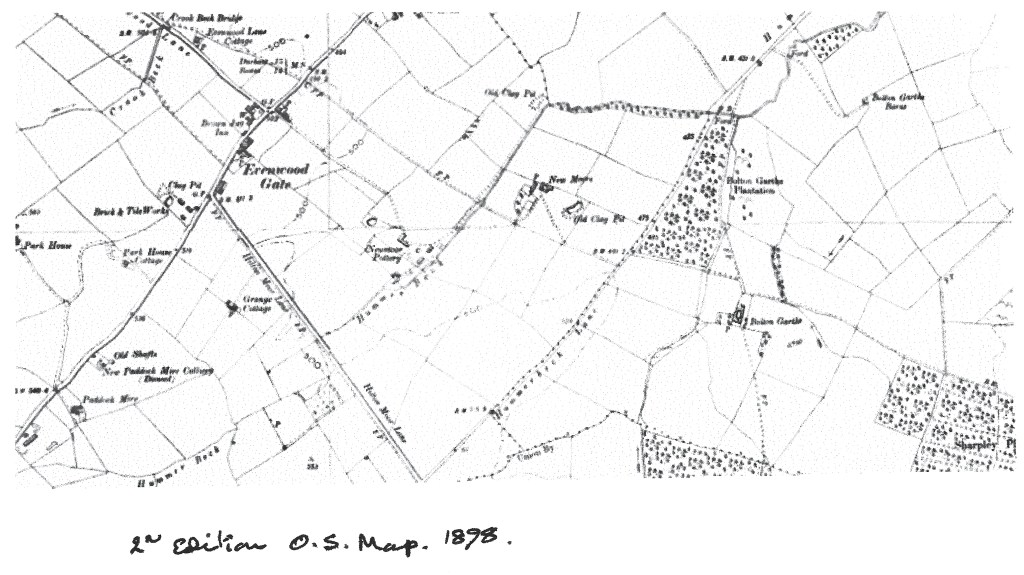

1898 OS Map (2nd edition)

The map shows Newmoor Pottery. There were 4 buildings and 4 small enclosures. Two old clay pits were illustrated, that shown on the 1858 OS map and another old clay pit, south east of New Moors Farm. There was also a brick and tile works consisting of 4 buildings and clay pit opposite Evenwood Gate and the road junction with Hilton Moor Lane. Today (2023), there is a pond on the site of the clay pit. The Hilton Tarn works were not shown therefore this concern must have closed down. The old quarries indicated on the earlier OS map were illustrated. Two disused collieries were recorded, namely New Paddock Mire Colliery (2 buildings and old shafts) and Paddock Mire Colliery (2 buildings).

Below: about 1898, a map to show New Moors pottery

About 1887 into the 1900s, Ralph Lax

In 1890, Henry Howe was a farmer at New Moors which infers that John Snowdon had moved on or died.[21] The pottery was then operated by Ralph Lax (1848-1915) and he was described as an, “earthenware manufacturer”[22] with 4 labourers who were John Brownbridge, John Pepper, William Vickers and James O’Brien.[23] Ralph Lax and his wife Elizabeth lived at Newmoors Pottery. He was a native of Southwick, Sunderland, the son of Robert and Elizabeth Lax and the family worked as potters.[24] By 1881, 33 years old Ralph worked as a “Potter”, then living at Lawrence Street, Sunderland with his wife Elizabeth. Sometime between 1881 and 1890, probably 1887, they moved to Newmoors Pottery. There is no record of Ralph Lax at the pottery beyond 1901,[25] By 1911, the Lax family was back in Sunderland. Ralph died in 1915. They probably left Evenwood Gate about 1902 and that seems to be the end of pottery manufacture at New Moors.

Below:

Products believed to be from Newmoors Pottery [26]

Salt jar with lid and a slipware decorated jug and below 2 cradles for small dolls.

By 1911, properties at Newmoors pottery were occupied by coal miners and their families. There was a local economic boom following the opening of Randolph Colliery and Coke Works at Evenwood in 1898. The families living there were John and Jane Bainbridge and their 8 children; John and Ethel Firby and their son, Harry; William and Sarah Longstaff and their 3 children; Joseph and Martha Priestley and their 2 children; John and Isabella Walton and 2 children, and John and Sarah Wilson and 7 children. Henry and Jane Howe and their son were still farming at New Moor Farm.

1914 OS Map (3rd edition)

By 1914 it is assumed that the pottery had closed. Buildings were now homes and named, “New Moor Cottages.” There was a block of 3 cottages to the west of the site and 2 individual buildings to the west. The 2 old clay pits near New Moors Farm were still evident in the landscape. The brick and tile works near Evenwood Gate was closed and then described as Park House Cottage. The site of the former Paddock Mire Colliery was the site of an old pottery, which evidently was of short duration. The old quarries near the former Hilton Tarn brick and tile works were indicated on the map. There was a new colliery, the Sun Colliery, which was worked by a shaft and a drift. It was located to the immediate east of the Sun Inn and now under the A688 road.

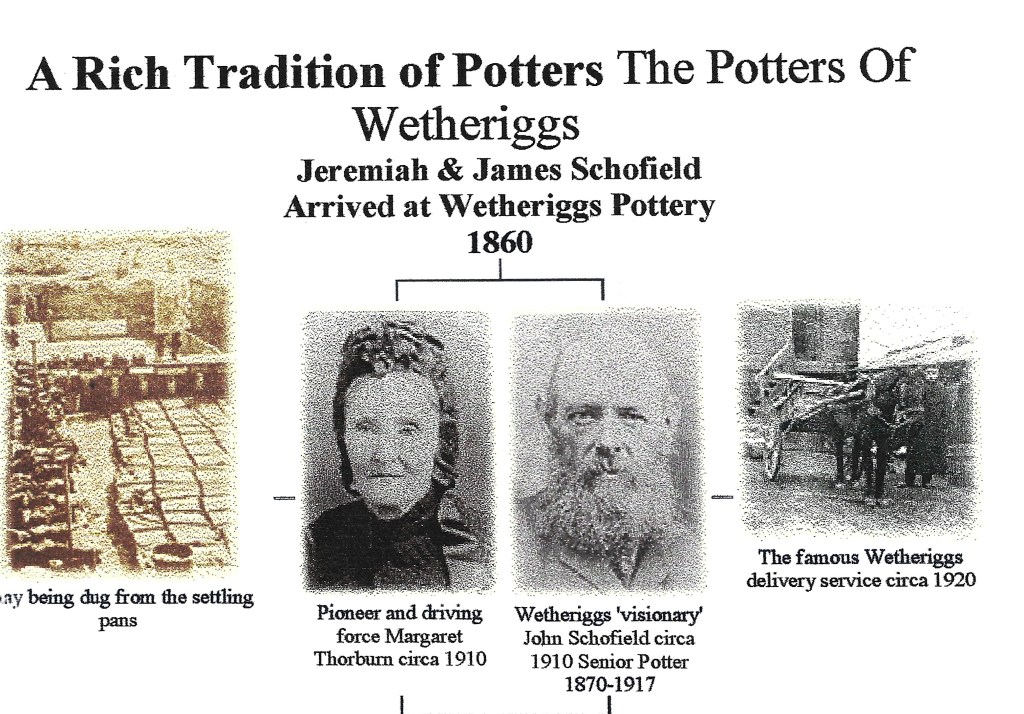

Wetheriggs Pottery, the Thorburn and Schofield Families [27]

Jeremiah, James and John Schofield and Margaret Thorburn were all, at various times, employed at Newmoors Pottery. They moved over to Wetheriggs Pottery, Clifton near Penrith, Westmorland to help built up this enterprise. Jeremiah and James Schofield were both born at Evenwood in the 1830s and went to Wetheriggs Pottery sometime between 1863 and 1867.[28] Some sources state 1860. Margaret Thorburn (1856-1937) was the daughter of Thomas and Margaret Thorburn. Thomas came to Newmoors for work between 1858 and 1860, when Margaret was still an infant. Thomas together with his daughters Jane Ann and Margaret all worked there. In 1871, both the girls were described as a, “thrower’s assistant.” In 1881, Margaret was a, “pot burner’s labourer,” probably working with her father. Aged 25, Margaret was mother to 7 years old William Thorburn. In 1882, she married John Schofield, the marriage was registered at Bishop Auckland.[29] John Schofield was probably the son of James and Margaret Schofield and, in 1871, worked at Newmoors as a, “brown ware thrower.” John, Margaret and William went over to Westmorland about 1882/83. John and Margaret has 4 children namely Arthur, James, John and Ada and all were born at Clifton.

Wetheriggs Pottery was developed on land belonging to the Brougham Estate when clay from Clifton Dykes was used for the manufacture of bricks, tiles and pipes from 1855. It is believed that pottery production commenced about 1860. John and Margaret Schofield were the driving force behind the success of the pottery. John was senior potter from 1870 and he died in 1917, to be succeeded by Margaret. Upon her death in 1937, the works passed onto another relative, John Schofield. In 1952 Margaret Thorburn’s grandson, Harold[30] took over and ran the works until his retirement in 1973. The pottery was then bought by Peter Snell who underwent a year-long apprenticeship with Harold Thorburn. He sought to preserve the physical structure of the works by having it scheduled as a national monument. In 1990, Snell sold to Peter Strong, formerly of Soil Hill Pottery near Halifax, who in turn sold up in 1993. [31]

The pottery was listed as an Ancient Monument in 1973. The description is:[32]

“Kiln, workshops, drying shed, kiln room, steam house and blunger. 1855 as a brick and tileworks for the Brougham estate. Red brick walls, under pantile roofs with stone and brick chimney stacks. Single-storey buildings arranged in U-shape around a small courtyard, with attached steam house and blunger. Bee-hive kiln is within square brick building with plank doors. Adjoining long workshops have plank doors and casement windows. Right-angled range is divided into open-sided drying shed and enclosed kiln room. Rear steam house has plank doors and round-arched casement windows; tall square chimney stack. Adjoining blunger is a circular brick-lined pit with central pivoted paddle for mixing clay and water, powered by the steam engine in the steam house. A working pottery which continued using old methods of production until the mid C20. Now reopened as a working pottery, to which the public are admitted, preserving original machinery and traditional designs, but electrically fired kiln. See guide book, Wetheriggs Country Pottery, 1984. The present shop and house are not of special interest.”

Above: Wetheriggs Pottery photo attribution: Chris Allen

A book has been published about Wetheriggs (or Schofield’s) Pottery.[33] The pottery managed to survive when most other country potteries failed with the advent of industrialisation. The book records its transition from a locally based, brownware pottery to one which made “Art Wares” for a growing tourist market in the early part of the 20th century. The book consists of a history of the site and the Schofield family followed by a catalogue of 197 pieces of their wares. These Art Wares were distributed throughout the country and can be found in almost any town in the UK.

Below: Items believed to be from Wetheriggs Pottery

New Moors Cottages, Evenwood Gate

By 1939, eight properties at New Moors were occupied by Moses and Margaret Maughan and their son George; Theodore Riley; Joseph and Mary Stokeld and their daughter Mary; Alexander and Mary Lowe and 1 child; Arthur and Elizabeth Lee and their son, Albert; William and Ethel Metcalfe and 2 children; Thomas and Hilda Priestley and 3 children and Joseph and Martha Priestley and 3 children. New Moors Farm was worked by Frank Pearse, his sister Margaret and mother Mary.

Below: These 4 photographs show the New Moor Cottages[34]

Above: Front and rear elevations

Above: Outside toilets (netties) and the coal fired range

Acknowledgements

John Hay (Barningham) for the information regarding 1877-1887 the Sales Ledger.

Joanne Maddison for the 7 items of Newmoors and Wetheriggs pottery and family information.

Brenda Robinson for the Newmoors salt jar.

Aline Waites for assistance with Ancestry details.

Beamish Museum for photos.

WETHERIGGS COUNTRY POTTERY [35]

This is a slightly edited version of an article that appeared in the magazine Industrial History, Spring 1977, with no mention of the author’s name. If anyone knows contact details for the author or publisher will they please get in touch with me at the address on the homepage. (Page created 19/04/05. Last updated 05/04/20)

A short history

Wetheriggs is one of the very few surviving country potteries still producing traditional earthenware pottery. It was scheduled in 1973 as an Ancient Monument. Many tile-works were built in the Lake District in the 19th century, to make pipes for land drainage, and Wetheriggs was one of these. It was developed in the middle of the century on part of Lord Brougham’s estate, where there was a seam of red clay and the Eden Valley railway could bring coal and take away the pottery’s products.

Wetheriggs made kneading bowls for dough, bread crocks, barm pots for yeast for baking and brewing, barley wine flagons, syrup jars, vinegar bottles, milk and cream bowls, butter churns and pots, baking dishes, starch pans, tea-bottles for railwaymen, chamber pots, hen-feeders, beetle-traps, flower pots, animals feed troughs, and bricks, tiles and drainpipes.

The decline of earthenware potteries began in the last (19th) century. With urbanisation, fewer people made their own bread and brewed their own beer. Moreover, craftsmen found it hard to compete with factories; mass production brought the price of china down. At the beginning of the present (20th) century there were still over 100 earthenware potteries left in England. However, by 1945 there were under a dozen left. Each of these served a rural area. But even farms gave up using earthenware when centralised dairies collected the milk, and farmers gave up making butter and cheese and curing meat.

In order to survive, Wetheriggs made an increasing amount of horticultural and decorated ware. Flower pots, crocus bowls, strawberry pots and decorated vases were popular, and wholesale orders were taken for these. Visitors were encouraged to look around the pottery, and the post-war growth in tourism kept the pottery going, through the sale of decorated mugs, jugs, vases, candlesticks and salt-pots.

Preparing the clay

Red clay was dug by two men, using picks and shovels, from behind the pottery and from nearby claypits. It was taken to the blunger by wheelbarrow, or horse and cart, and more recently in bogies on a small narrow gauge railway by a pulley system linked to the steam engine.

The Blunger was a steam-driven wash-mill to clean the clay of stones and sand. Blunging began in February so that the clay could dry in the settling pans in the summer. The tines on the rotating arms of the blunger broke down the lumps of clay into a liquid slurry with water from a reservoir behind the pottery. The cobbles, stones and sand in the clay sank to the bottom of the blunger pit, and the slurry was drained off into the settling pans via a long channel called the grip. The length and gradient of the grip allowed most of the remaining sand in the slurry to be deposited, and two screens sieved out floating matter such as grass and twigs. The sand and gravel were dug out and sold to builders.

The Settling Pans, or sun kilns, dried out the liquid clay until ready for use. As the clay particles settled, water was drained off, and the clay dried in the sun until the surface cracked but it was still damp underneath. A layer of sand on the bottom of the settling pan made cutting the clay out easier. The clay was chopped with a spade into pieces weighing 3 stones, called lifts, and these were barrowed to the claystore, or ‘dess’. The clay nearest the entrance to the pan was sandier, or coarser, and this was used for garden ware. A smaller settling pan was built in order to dry out the clay more quickly. Slurry was pumped from the corner of the main settling pan into this one, using s steam pump. Until the First World War there was also a boiling pan to dry the clay. This was a low-walled area of fireclay flags, approximately 60 feet by 8 feet, heated from below by a ducted coal fire. The slurry was barrowed up a ramp and tipped to a depth of six inches. Drying only took a day, and gave the best clay for use – it remained warm to the touch for several days.

The Pugmill. Clay was stored in the dess, where it would sour, or improve with keeping. Enough clay for a kiln-load of pottery – i.e. 350 lifts – would be pugged at a time. Pugging blends the clay into an even consistency and removes most of the air pockets. Inside the pugmill, the rectangular cast-iron box, a series of blades mounted along a revolving spindle compress the clay and force it out in a continuous length.

Wedging. One man’s job was to prepare the clay for the thrower on the wedging block, which has plaster surfaces to absorb excess moisture. Wedging is a rhythmical sequence of slicing a lift of clay, raising it above one’s head, and slapping it together. This is done until the clay has a fine, even consistency, and then it is cut into pieces with a wire and kneaded into balls for throwing, estimating the weight by eye.

Throwing

The wheel was steam-driven. The speed-control pedal is based upon counter-balance, so it has a very light touch. A continuously moving fly-wheel transferred the power to the wheelhead by means of a leather-faced drive-wheel. Speed was achieved by pushing this to the edge of the fly-wheel.

The wheel was kept in use throughout the day; the thrower was supplied with balls of clay and he filled up 8 feet boards with pots of uniform size and shape. The clay was centred on the wheel and then drawn up into a pot, using the centrifugal pressure produced by the rotation of the wheel. The potter used his body weight to help shape the pot. The art was of minimum effort for maximum effect.

Before throwing big ware, a round bat would be stuck onto the wheelhead with a ring of clay, so that the finished pot could be lifted off the wheel on the bat. The 4 feet bread crocks were thrown in 2 sections and joined together afterwards.

Making a living out of pottery depended upon the speed of production, so designs were simple. A good thrower could make three 4-inch flower-pots a minute, and could throw a pot from 60 lbs of clay.

Moulding

Most pottery was thrown on the wheel, but square and rectangular baking dishes were moulded. The clay was rolled out and either laid over a plaster mould, or placed in a hollow press-mould. The edges were scalloped with the thumb to leave gaps for the hot gases to escape when the dishes were fired face to face. For a short time, tea-pots were made, using press-moulded handles and spouts, but it was difficult to compete with factory prices.

Until the First World War moulded flower pots were produced using a jigger and jolley. Balls of clay were placed into plaster moulds rotated by the jolley, and the jigger forced the clay into the right shape. This mechanical process allowed unskilled workers to produce large numbers of identical pots, which would nest inside each other.

The pottery was producing mainly pipes for land drainage, roofing tiles and bricks when it began, and continued to make these until this (20th) century. Clay from the settling pans was fed into extrusion machines near the pugmill, and in the gallery of the steam-shed. The clay was forced through dies into pipe, brick or tile shapes. These were cut off at the required length and dried outside in the drying sheds: open-sided buildings with racks. Firing was done in two Newcastle-style kilns which lay on the east side of the beehive kiln; this wall is particularly thick because it formed part of the brick kilns.

Fettling

Fettling is the word used for the processes between throwing and firing the pottery. The day after throwing the pots are firm enough to be picked up, wiped free of any irregularities, and stamped with the pottery’s mark. Strap handles for big ware such as bread crocks were pulled from a lump of clay and attached with slurry. Handles for jugs and mugs were rolled out into sausage shapes.

Before firing, pottery has to be dried out. There are racks for drying above the heater benches which run the length of the pottery, and in the back of the kiln room. The boards of pots were moved around systematically to ensure drying at the right rate, and carried on the shoulder to the different areas for slipping, glazing and firing.

Decorating and glazing

Decorated slipware. Most farm crocks were not decorated, except perhaps for a few lines of white slip, blown out of an earthenware bottle through a goose quill, while the pot was still on the wheel. Salt-pots and pie-dishes were decorated with patterns, the slip being trailed onto the damp clay from a cow’s horn with a goose quill in the tip. Two designs were traditionally used at Wetheriggs – a feather, and a wavy line with fronds on it. Over the years these designs were simplified into a more abstract pattern.

White clay is less common than red clay, and was used to colour the pots where white was more practical, for example inside bowls and jugs. It was dried, powdered, and soaked with water in a barrel to make it a creamy liquid called slip. This was sieved, and ballclay was added so that the slip would shrink at the same rate as the red clay, and not peel off. pots were coated with slip when leather-hard.

As the sales of family pottery declined, more decorative coloured ware was made. The white slip was stained with copper oxide for green and cobalt for blue.

Feathering and marbling were two methods used to decorate pottery with slip. Pie-dishes were feathered by firstly coating the inside with slip, and then slip-trailing parallel lines across the dish in a different colour. Feather-like patterns were made by dragging a fine pen across the lines of slip-trailing. Marbling was done by dropping a pot into one slip and then flicking slip of another colour onto it with the finger tips. The slips could be made to run into each other to give a marbled effect by vigorously shaking the pot.

Glazing. Traditionally, clear glazes made from lead were used to seal earthenware and make it non-porous. Red lead was imported from Newcastle and mixed in a barrel with ball-clay, ground flint and water. The liquid glaze was used like a slip to coat the pots before they were dry. Lead glazes gave earthenware a rich, buttery colour on top of a white slip, and the iron in the clay body was drawn out to give a flecked appearance.

The kiln

Beehive kilns are now rare. They are cone-shaped, like the old straw skeps for bees, with a 2 feet wide smoke outlet at the top, and a short chimney over this. The kiln was coal-fired: there were 8 fireboxes around the kiln. The arch bricks inside these fireboxes, the throats – the narrow entrances from the fireboxes to the kilns – were replaced regularly. The bricks were cemented together with fireclay, using wooden arches for support. Long-flame coal was tipped from the railway wagons and piled in each corner of the kiln-room, ready for stoking.

The shelving and saggars in the kiln were made of a mixture of clay and fireclay, to withstand repeated firings. Saggars are boxes made by rolling out the clay and fireclay mixture, and forming shapes around wooden moulds. Glazed pots were placed inside the saggars during firing to protect them from the flames, and they were stacked up in the kiln.

Rings were made to prevent the glazed surfaces of stacks of bowls touching while firing. Fireclay was beaten into sanded ring-moulds with a saggar-maker’s hammer, and carefully levelled. Any uneveness in the rings would make it difficult to stack a pile of pancheons. Three-pointed stilts were used to life the bottoms of smaller glazed ware off the bottoms of the saggars so that they would not stick. Animals feed troughs were also made of fireclay, for extra strength.

Firing

The shelving in the kiln was filled with large pots such as bread crocks, egg-preserving jars, and large jugs. Smaller pots were placed in the saggars. As many as 60 pancheons were stacked on rings from the floor to the top of the kiln. Altogether it held 6000 to 7000 articles each firing, but it could hold as many as 20,000 plant pots when these were in demand in the spring.

The kiln was fired about 3 times a month, and big pots were stacked around it to dry out. The doorway was bricked up and the 8 fires were lit and stoked up gradually until they filled two-thirds of the fire-boxes. These were then bricked up, except for a gap at the top for stoking. The flames issued between the shelving in the kiln, and through a hole in the centre of the floor. Stoking was continuous, using about 6 tons of coal, until the kiln reached a temperature of over 1000˚C, in 30 to 36 hours. Draught holes between the firebox arch at the throat of the kiln were used during the later stages of firing to increase the length of flame in the chamber and to maintain an oxidised atmosphere.

In order to gauge the temperature, test rings were withdrawn from the kiln on rods, through spyholes. When the glaze on these rings fluxed, the kiln was ready to close down. Two spyholes were used; one in the doorway to test the temperature at floor level, and one at the back for the heat at the top.

The kiln had to cool slowly, over 3 days, or the glaze on the pots would crack. The fireboxes were bricked up to the top, and a heavy metal lid pulled over the top of the kiln to damp it down. After unpacking the kiln, the cinders were raked from the fireboxes and sold to farmers for repairing farm roads. The pottery was stored in the warehouse, and packed for despatch in straw and hazel-wood crates.

Miscellaneous

Coal was used in the brick kilns, the beehive kiln, the steam engine, the boiling pan, and the drying flags in the pottery. It was also sold. There was a weighbridge for carts by the front gate. Coal was brought to the pottery up the siding between the kiln and the house until 1961, when the line was closed and the kiln ceased to be used.

The steam-shed housed an 8.5 h.p. steam engine which powered the blunger, clay bogies, pugmill, wheel and sawbench. It required constant stoking and was replaced by a diesel engine before the Second World War.

The blacksmith’s shop was used in the construction and maintenance of the machinery on the site, for repairing carts and shoeing horses.

The warehouse was on railway land, and rented for a nominal sum.

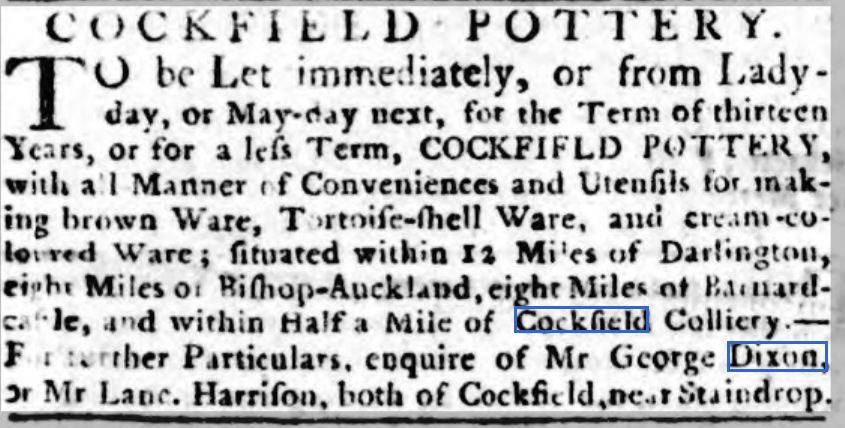

WHERE WAS COCKFIELD POTTERY?

This undated, unattributed article has been found. Does anybody have any ideas where Cockfield Pottery was located? Our good friend, John Hallimond has no idea.

Kevin Richardson 25 October 2023

REFERENCES

[1] There are 2 spellings – Newmoors Pottery and New Moors Pottery. New Moor Farm is 3 separate words, sometimes New Moors Farm. These variations are used in Directories, Census and Tax Returns and repeated here in the different forms.

[2] C.1990 This photo taken in the late Kathleen MacMillan’s home, “Kiloran.”

[3] The 1783, 1785, 1788, 1798, 1803, 1810, 1812, 1817 and 1824 Tax Returns.

[4] The 1827 Tax Return records 3 entries involving the Ramshay family including Mrs. Ramshay owning property occupied by George Young (junior), a house and pottery.

[5] 1828 White’s Gazetteer of Durham.

[6] In 1830, their son William Ramshay, of Leeming erected the headstone. Presumably, he was the eldest son. George Ramsahw may well have been serving abroad in the Royal Navy.

[7] The 1830 Tax Return shows 2 entries for George Ramshay owning and occupying land and house & land. Also William Ramshay’s 2 properties were both occupied by William Sutton, a house & land and another property, a pottery. To date, a suitable candidate has not been identified for William Sutton.

[8] Poll Book for the County of Durham December 1832

[9] 1841 Census

[10] 1841 Census

[11] 1851 Census

[12] 1851 Rate Book

[13] 1851 records John Thompson aged 68 and John Thompson aged 25 farmers of 225 acres at Staindrop Field House.

[14] The Brown Jug PH, presumably named after pottery products.

[15] 1851 Rate Book

[16] The 1851 Rate Book records Park House Colliery owned by William Thompson and occupied by William Robinson & Co.

[17] The 1851 Rate Book records Paddock Mire Colliery owned by Mrs. Bell and occupied by Gilbert Hunter & Co.

[18] The 1861 census records a name which is difficult to decipher, possibly Thursfield but there is no record of such a name.

[19] Details of the New Moors Pottery Sales Ledger provided by John Hay, Barningham.

[20] A “pankin” is defined as, “a small pan or jar of earthenware sometimes a jar of any size.”

[21] John Snowdon’s death has not been identified.

[22] 1890, 1891 and 1901 Kelly’s Directory & 1894 Whellan’s Directory

[23] 1891 Census

[24] 1851, 1861 & 1871 Census

[25] 1902, 1910 and 1921 Kelly’s Directory’s show Henry Howe as a farmer at New Moor but there is no mention of Ralph Lax.

[26] The slipware jug is similar to an item manufactured at Wetheriggs Pottery

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wetheriggs_Pottery

[28] Census details, having consideration to the year and birth places of children

[29] England & Wales Marriage Index 1837-1915, Vol.0a p.276 Auckland 1982 Q1

[30] Harold Thorburn (1903-1981), his father was William Thorburn (1874-1941) and grandmother was Margaret Schofield nee Thorburn (1856-1937).

[31] https://www.academia.edu/5591111/Littlethorpe_Potteries_in_the_Context_of_British_Country_Pottery_Making

[32] https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1145365?section=official-list-entry

[33] “Wetheriggs Pottery: a history and collectors guide” 1998 B. Blenkinsopp

[34] Photographs courtesy of Beamish Museum

[35] https://www.cumbria-industries.org.uk/a-z-of-industries/pottery/wetheriggs-country-pottery/