James Wilson can be regarded as one of the pioneers for improving conditions of working people during the 19th century – a visionary man who championed many causes for the under privileged in South West County Durham. He was a major figure in the 1844 pitman’s strike but following the return to work, he was victimised and moved out of Evenwood to Crook.

Arguably, Evenwood’s loss was Crook’s gain.

1819, James Wilson was born, the son of Thomas and Isabel Wilson, at Warcop, Westmorland. In 1832, the Wilson family settled in Evenwood – they came for work. With the coming of the railway to the Gaunless Valley in 1830, the coal industry began to develop on a greater scale than hitherto. Employment was available in railway construction and coal mining. The population of the Parish of Evenwood and Barony rose from 793 in 1801 to 1,019 in 1831 then the next decade saw a 69.8% increase to 1,729 in 1841.

By 1832, James would have been 13 years old and ready to work at the local colliery, Norwood Colliery. That year, there was a pitmen’s strike but those at Norwood Colliery were not part of the Northern Pitmen’s Union. The nearest lodge was Black Boy at Auckland Park. In all probability, they would have been totally unaware of the strike since the collieries which were affected were located some way to the north. News travelled slowly. Most of the pitmen and their families could not read or write, the newspapers of the day were of no use to them and only “word of mouth” would have been likely to have raised any support.

During the mid to late 1830’s, the Durham County Coal Company and other concerns developed pits in the Evenwood area – the new Norwood Colliery, Gordon, Thrushwood, Tees Hetton, Evenwood New Winning and Craggwood Colliery.

In 1838, at the age of 18/19, James Wilson became a local preacher among the Primitive Methodists. This brand of Methodism was known as, “the Ranters” due to the often fiery delivery of the preachers’ sermons. There was a Primitive Methodist Chapel in Evenwood close to the pitmen’s houses. This housing, known as the Oaks, consisted of 56 dwellings in 4 terraced rows, Front and Back Row and 2 known as Cross Row. Other pitmen and their families lived at Gordon New Row (later to be part of the small village of Ramshaw) and other houses in Evenwood. The 1841 census indicates that most dwellings at the Oaks were all occupied. James Wilson, then aged 20, did not live there. He was recorded as living at Evenwood but the street was not named.

Below: 1841 Census Return for Evenwood. 20 years old James Wilson lodged with Isabella Stobart and Ann Deakon (?)

The pitmen’s strike of 1844 was the event when James Wilson, then aged about 25, came to the attention of the public. No doubt, his experience at public speaking, influenced the decision to select him as an advocate for the miners’ cause. Their case was misrepresented in the press, so the leading members of the Durham and Northumberland miners, chose 12 “practical pitmen” to go to London and address the general public at pre-arranged meetings, in order to seek support. They became known as the “Twelve Apostles”. Ultimately, this industrial action was lost. Many of the pitmen’s leaders were subsequently victimised, including James Wilson. They could not find work locally and were forced into migration. James Wilson left Evenwood to settle in Crook, some 12 miles to the north.

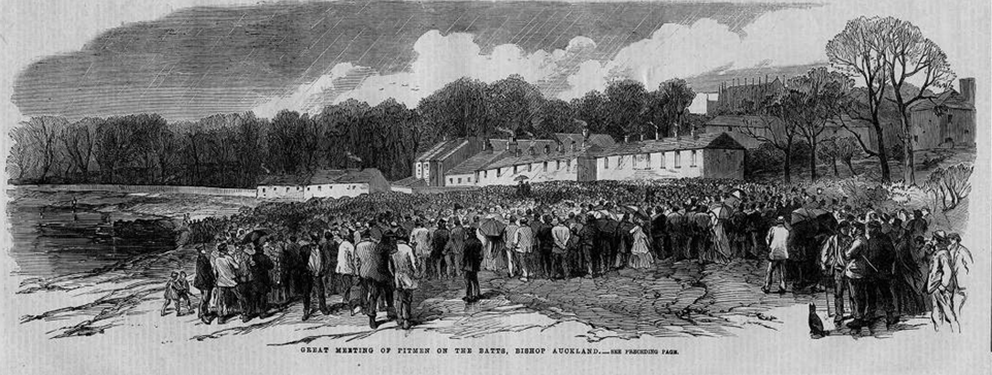

Below:1844, The Pitmen’s Meeting at Bishop Auckland addressed by James Wilson

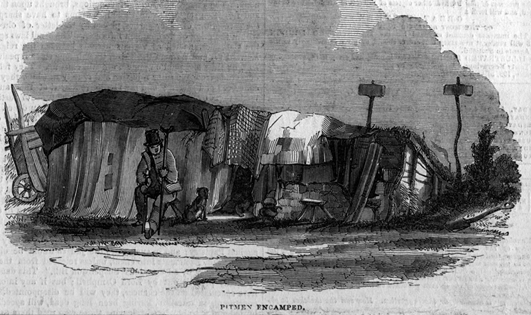

Below: An Evicted Pitman’s Camp at West Auckland

James Wilson’s future brother-in-law, Henry Whitfield, was another to leave Evenwood for Crook. The Primitive Methodists in Crook were led by a nucleus of men originally from Westmorland – George Calvert, James Willan, John Parkin, James Wilson and Henry Whitfield. James Wilson married Elizabeth Whitfield in May 1845. They had 5 children.

Below: Henry Whitfield, James’ brother-in-law, another influential Crook Primitive Methodist

The strike, victimisation and emigration of some pitmen together with the demise of the Durham County Coal Company led to a 20% fall in population of the Evenwood and Barony Parish between 1841 and 1851. In fact, the Durham County Coal Company and the Northern Coal Mining Company (owners of Craggwood Colliery) both went into liquidation.

However, Crook was one of the “new” colliery towns to develop from the 1850 onwards. Its population in 1811 was 176, in 1831 it was 200 but by 1851 it had grown over tenfold to 2,764, by 1871 to 9,401 and by 1891 to 11,430. Messrs. Pease and Partners were responsible for its development due to its interest in coal mining and coke manufacture. Its extensive Bankfoot plant provided coke for the iron and steel industry on Teesside.

James Wilson moved to Crook and prospered as a local businessman who lived by his religious and social beliefs and held many positions in public life including:

- one of the leading advocates of the Primitive Methodist Chapel, built in 1847.

- one of the promotors of the Mechanic’s Institute, established 9 August 1848.

- Chairman of Crook Gas Company, incorporated 18 September 1856.

- Treasurer of the Trust Fund of the new PM Chapel, built 1868, opened 1869.

- Overseer of the Poor.

- one of the promotors of the Temperance Society.

Below: 1869 The Crook Primitive Methodist Church

In political life, he was chairman of the Liberal Committee formed to support the Joseph Pease and Frederick Beaumont candidacy for the South Durham constituency in the 1868 and 1874 parliamentary elections. At this time, the Liberal Party [the Whigs] was the most radical of the 2 political parties. The Conservatives [the Tories] were keen to retain the “status quo”, the rule of the elite class, capitalism and arguably subjugation of the workers. A political party with the interests of the working population had not yet been formed. Most working people did not have the vote. Both campaigns were successful for the Whigs in South Durham, which was not really surprising given the influential position of the Pease family.

By 1871, James and Elizabeth Wilson, lived at South Street, Crook where James was recorded as, “Grocer, Draper, Druggist. Primitive Methodist Preacher”.

Below: 1871 Census Return

James Wilson died, 24 April 1875, aged 56.

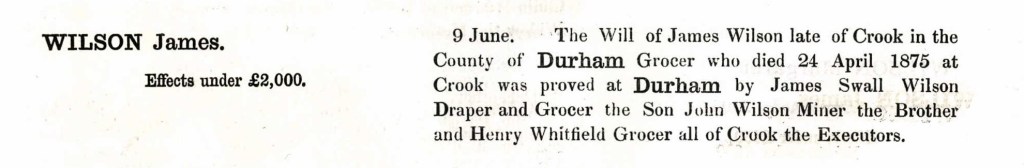

Below: 1875 Details of James Wilson’s will

James Wilson can be regarded as one of the pioneers for improving conditions of working people – a great man championing many causes for the under privileged in South West County Durham.

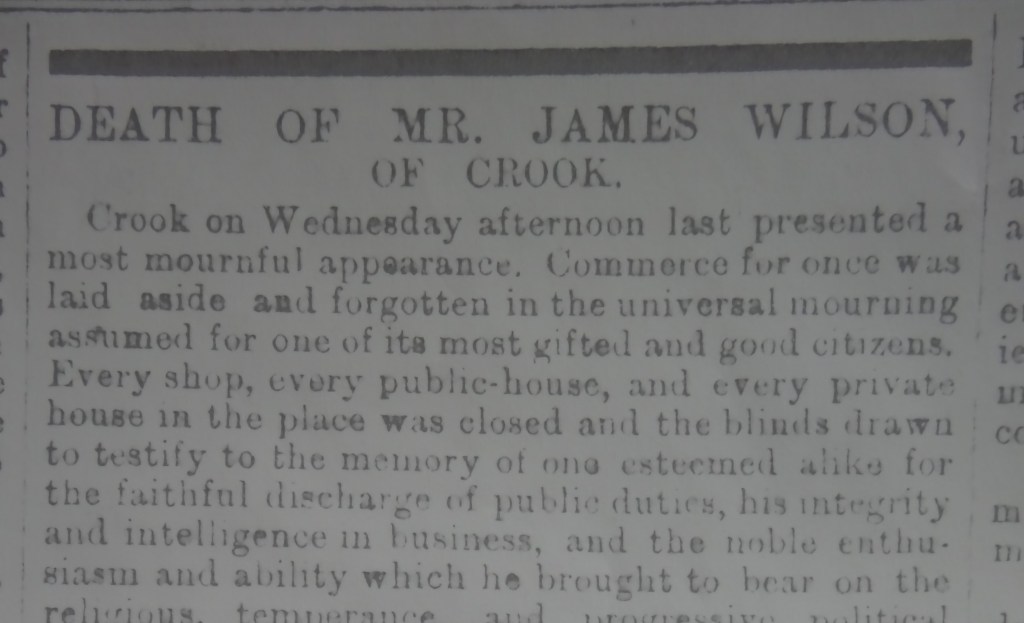

Below: The Durham Chronicle 30 April 1875, an obituary to James Wilson

1875 April 30: Obituary of James Wilson: A transcript

“DEATH OF JAMES WILSON OF CROOK

Crook on Wednesday afternoon last presented a most mournful appearance. Commerce for once was laid aside and forgotten in the universal mourning assumed for one of its most gifted and good citizens. Every shop, every public house and every private house in the place was closed and the binds drawn to testify to the memory of one of the esteemed alike for the faithful discharge of public duties, his integrity and intelligence in business and the noble enthusiasm and ability which he brought to bear on the religious, temperance and progressive political welfare of the district in which his lot was cast. For each of these movements he was sound, energetic and eloquent advocate. Few men with his opportunities, turned to such good and faithful an account the talents with which they are endowed. He was a sincere friend of all that was good and true and a staunch opponent of all vice and meanness in whatever guise he met them. With unwearied industry and unflagging zeal, he battled with and overcame great difficulties and discouragements both pecuniary and mentally and to within a few months of his death retained the full force of his varied powers. His enthusiasm and zeal in the various movements in which he was incessantly engaged never outran his discretion. He always cultivated and retained the esteem and friendly relationship of his opponents so necessary to the peace and goodwill of his neighbours and the success of the cause in which he was engaged. This was abundantly manifested at his funeral when Churchmen and Nonconformists, master and workmen, gentlemen tradesmen and publican all joined to do the honour to his memory and for once forgot their little differences and united to testify to the loss they had sustained in the death of the deceased.

Mr. Wilson died at his residence on Saturday morning April 24th, after a lingering illness. He was a native of Westmorland and came with his parents into this county in the year 1832. He then became a coal miner and was one of the early reformers who sought to ameliorate the miner’s condition. He was one of the “Apostles”, as they were then called, who, during the agitation of 1844, went to London to plead the pitman’s cause, holding meetings and seeking interviews with gentlemen likely to aid them in their mission. They secured the sympathy of many of the Radical Reformers of that day and were especially befriended by Thomas Duncombe MP for Finsbury and Fergus O’Connor. Soon after Mr. Wilson’s return from London, he settled in Crook and commenced business in a very small way and by his energy and industry he became one of the principal tradesmen in the place. Though he advanced in his social condition he remained faithful to his political principles and ever took an active part in matters that contributed to the welfare of Crook inhabitants. He was one of the projectors of the Crook Gas Company and for some time was chairman of the directors. He was also an overseer of the poor. He was deeply interested in the erection of the British Schools which have been such a boon to the rising generation of the neighbourhood. He rendered service in securing a cemetery and until a Methodist minister was located in Crook, he was constantly in request to perform the last religious service for the dead, which he did without fee or charge. He was one of the promoters of the Mechanics Institution and the Temperance Society had in him an active and generous friend. He was chairman of the local Liberal committee at the last General Election and was too prodigal in his strength in his anxiety to secure the return to Parliament of Messrs. Pease and Beaumont. All through his public life Mr. Wilson was connected with the Primitive Methodists, a people who have done much to improve the moral condition of the mining population of this county. In the year 1838 he became one of their lay preachers. His religious and intellectual earnestness, along with his natural eloquence, rendered him especially useful in conducting religious services. Primitive Methodism in Crook is doubtless much indebted to him for its present position. He took an active part in the erection of their first chapel in the year 1847, which is now the property of the Temperance Society. In the year 1868 they built their present substantial and beautiful chapel and school room and up to his death he was treasurer for the trust fund. He was twice elected by the Crook Circuit to represent them at their District Meeting. The District Meeting testified their appreciation of his worth and ability by twice electing him as a delegate to the Conference, no mean honour for a Methodist layman to enjoy. Mr. Wilson’s success in life was based on his religious character and his unceasing industry. He was in the strictest sense a self-made man. In his death Crook has lost one of its most respected tradesmen and its political and religious institutions, a devoted friend and advocate. He leaves a widow, two daughters and three sons.

The funeral cortege assembled in the Market Place at three o’clock. There were a vast number of people present and the whole of the tradesmen of Crook attended in a body to accompany the remains of the deceased to their last resting place, amongst them we noticed the Rev. T. King, rector of Crook, Revd. Pratt Bishop Auckland; Rev. G. Graham Shildon; Rev. W. Robson Motherwell, Scotland; Rev. G. Snaith Tow Law; Rev R. Hind Waterhouses; Rev. T. Dods Crook; Rev. T. Hepton Crook; Rev. J.W. Walsh, Rev. E. Sones, Rev. G. Renton, Rev. J. Waite, Superintendent Minister, H. Tuke Esq. Bishop Auckland, A.J. Kellett Esq. Bishop Auckland, T. Dixon Esq. Crook, G. Coward Esq. Durham, T. Revealy Esq. Newcastle, James Fowler Esq. Durham, J. Burden Esq. Durham, S. Hodgson Esq. Sunderland, G. Plank Esq. Sunderland, Mr. Fleming Wolsingham, Mr. Anderson Witton-le-Wear, Mr. F. Spoor, Mr. B. Spoor and Mr. G. Dent Witton Park, Mr. J. Graham, Mr. G. Willan and Mr. G. Calvert, trustees of the Primitive Chapel, Mr. J. Birbeck & &. A simple hymn was sung over the remains of the deceased at the door, after which the coffin was placed in the hearse. The procession then formed four deep and walked to the beautiful and commodious Primitive Methodist Chapel, in which the deceased was deeply interested and towards the building, support and success of which he contributed liberally both in time and money and his labours contributed largely to build up and establish one of the largest and most powerful Primitive Methodist Societies in the North. In the chapel a hymn was sung and the service was conducted by the Rev. J. Waite, superintendent of the circuit, assisted by the Rev. J. Snaith of Tow Law. The Rev. J. Waite read a portion of scripture appropriate for the occasion and afterwards made a few remarks pertaining to the solemn occasion, in the course of which he said that considering the unusually large attendance at this burial service and its mixed character, he might well ask, “What meaneth this great gathering of people?” It certainly testified that he whose remains they were following to the grave was a public man. Mr. Wilson was a public man of the best kind. It was one thing to be a public man and another to be a public benefactor. A man may be a favourite with people and yet he may not be promoting the good of people. Mr. Wilson was known amongst the people of the neighbourhood for his active services to promote their political, social and religious welfare. It was his wish and endeavour to be the friend of all and enemy of none. Though he was most assiduous in his attention to his own business, in which his success was remarkable, he found time to promote and aid any object that was likely to be a benefit to this locality and its population. He was ready to assist in all ameliorative and progressive movements. His first appearance before the general public was thirty-one years ago, in the year 1844, when he along with others, went about the country, even to London, to improve the miners’ condition, which was certainly so distressing as to demand redress and improvement. And in his last days he rejoiced exceedingly to see the improved condition of the coal miners in our northern counties. Mr. Wilson was also a Christian. No-one could be long in his presence without feeling this. Men of bad dispositions, having evil designs and men unscrupulous in their methods of operation, providing their ends be accomplished, shrunk from his presence. His Christian character was not forgotten or cast aside in dealing with secular and public affairs. The rev. gentlemen concluded his brief sketch with a description of the deceased last moments and expressed a wish that he and all hearers might have such a death as James Wilson. Mr. H. Brotherton of Bishop Auckland very ably officiated at the organ and as the corpse was borne out of the chapel played the effecting “Dead March in Saul”. His remains were then deposited in the Crook Cemetery.”

1844 THE PITMEN’S STRIKE

The strike took place following a period of wage reductions. At the beginning of 1843, the men received 30 shillings per fortnight but by April 1844, wages had been reduced to 20 shillings, which, over the 18-month period represented a reduction of a third. There were many other grievances such as the dislike of the Bond [their yearly agreement for the terms of their labour], a desire to have the mines regulated and inspected and the right to have a trade union.

An explanation of the Bond is given below:

“The annual bond in Northumberland and Durham had its origins in the traditional method of binding farm servants and labourers and the signing ceremony was in many areas, accompanied by a feast day comparable to the hiring fairs in rural districts. Reflecting its agricultural origins, the colliers’ bond ran originally from autumn to autumn, but as this caused a hitch in production at a time of peak sales of coal, the term was altered in 1812 to run from April to April.

Initially, it was the custom for the clauses of the bond to be read out before the colliers signed it, but this could take some time since by the 1830’s the document had increased in complexity and could be several thousands of words long, including details of payment, instructions on methods of working, colliery regulations, and where colliery housing was provided, as was usual in the north‐east, conditions of tenancy. (Glass to be kept in good repair, fourteen days to get out if employment ceased, no dogs to be kept, were typical conditions). It even contained a provision for arbitration in the case of disputes.

The bond was couched in such legal language, which submerged itself from time to time into reams of dependant clauses that it can have meant little to those literate colliers able to read it at leisure, and must have meant even less to those who heard it gabbled at top speed. An official present at one signing questioned some of the colliers about the bond and, “scarcely one of the witnesses whom I examined could give any outline of the provisions of the agreement to which they had thus formally consented, though well acquainted with the bearing of some stipulations which they considered grievances”.

‘Signing’ was something of a misnomer, because, regardless of whether a collier could sign his name in script, it had become the practice, for the sake of speed, to make a mark. The same official reported, “I observed more than one hundred persons indicate their assent and signature by stretching their hands over the shoulder of the agent and touching the top of his pen while he was affixing the cross to their names, and this, I was told, was a common practice”.

Although the bond gave colliers a measure of security and even contained in some instances, provisions for short time working, or what would today be called a guaranteed working week, it had a number of drawbacks. Because the demand for labour was variable – a cold snap in London, the north‐east’s main market, or the not infrequent sinking of a London bound coaster could result in an unexpected leap in demand – extra short term help was obtained by taking on unbound men, who might be migrants or men whom former employers had refused to sign again.

In Durham, in 1841, it was that as much as one quarter of the collier workforce was “floating”. Although the unbound men were subject to the same conditions as those who had signed the bond, there was always the suspicion that they might, in the event of a dispute, work on regardless or accept a lower rate for the job. Indeed, this often happened, and here lies the germ of the blackleg problem for which the Northumberland and Durham coalfield was, in the latter half of the 19th century to become notorious.

The bond was a legal document, and a man who broke its terms laid himself open to fines, dismissal, or, if he left his place of work before he had worked out his time, a term in prison. In the South Durham district in the year 1839 – 40, 172 men spent periods in Durham jail for various bond offences. Not being under these constraints, the unbound men were resented and so the bond became associated with the beginnings of trade union activity, sporadic though this was.

The disadvantage of the annual bond from the points of view of both employer and employed, was that it focussed the heat of negotiations on one month or less in the year. Until 1812, the autumn signings gave the colliers an advantage, since the pressure of demand was an incentive for the masters to settle. After 1812, with the spring signing, the advantage switched; the masters could bear with a dispute during the quiet summer months. But, either way, the signing of the bond became an occasion for on the one hand, a tightening of the screws on colliers, or, on the other, the rehearsal of old and new grievances. “

Such was the system of hiring pitmen – on a yearly basis, with most men signing their contract with a cross since they could not read or write and often they had not heard or understood the terms of the bond. Fines were imposed for trivial transgressions and with the bond backed up by the law, the threat of imprisonment was constant. The men considered that this system had to change and allied with the reduction in wages, the time had come to take action. They appointed W. P. Roberts, a Chartist solicitor, from Bristol, as their “Attorney General”.

On 31 March, the contracts of all the miners of Northumberland and Durham expired and so they instructed Roberts to draw up a new agreement, in which the men demanded:

- Payment by weight instead of measure;

- Determination of weight by means of ordinary scales subject to the public inspectors;

- Half-yearly renewal of contracts;

- Abolition of the fines system and payment according to work actually done;

- The employers to guarantee to miners in their exclusive service at least four days’ work per week, or wages for the same.

This agreement was submitted to the coal owners and a deputation was appointed to negotiate with them. But, the coal owners totally ignored the miners’ approach. The pitmen were told that the owners would deal with single workmen only and would never recognise any union of pitmen. They also submitted an agreement of their own which ignored all the foregoing points, which, naturally, was refused by the miners.

The pitmen’s cause was supported by the radical M.P., T.S. Duncombe, the Chartist leader Fergus O’Connor and the Chartist newspapers. The Northern Star and The Northern Liberator supported them wholeheartedly against the hostility of the national press and local Tory and Liberal papers, The Durham Advertiser and The Durham Chronicle. 40,000 miners laid down their picks and every mine in the county stood empty. The funds of the Union were such that for several months a weekly contribution of 2s. 6d. could be assured to each family. Roberts organised both strike and agitation, arranged for the holding of meetings, traversed England from one end to the other, preached peaceful and legal agitation, and carried on a crusade against the despotic Justices of the Peace.

Below: Fergus O’Connor

Above: Thomas S. Duncombe

Above: William P. Roberts.

Northumberland and Tyneside pitmen were fairly solid, but some of the newer Durham collieries contained minorities of workers who continued to work after 8 April but stopped working on the following dates:

- 8 April: South Hetton was stopped.

- 9 April: Thornley, Pittington, Rainton, Penshaw and North Hetton.

- 10 April: Haswell, Shotton, Kelloe and South Wingate.

- 12 April: Castle Eden, Trimdon, Evenwood, Coxhoe Cassop, Ludworth, Murton, Monkwearmouth and Edmondsley.

At the time of the strike, the Durham County Coal Company employed about 350 men and boys at its Evenwood Colliery. It was located on the estate of John Bowes of Streatlam Castle, near Barnard Castle. He was the local Member of Parliament when only the privileged few had the vote, working men and women did not.

As indicated above, James Wilson was one the “Twelve Apostles” who toured the country to spread the message of their cause and raise funds to support miners’ families. At several public meetings James Wilson shared the platform with Thomas Duncombe and Fergus O’Connor. In June at Saville House, Leicester Square, London, Wilson followed Duncombe. He told his audience that the miners sought, “a living in return for toil” and referred to. “poor man’s labour” as, “the rich man’s wealth”. He told how at the colliery in Evenwood in which he worked, a new viewer had been appointed [probably L.P. Booth] and he claimed to have scheme by which he wished to benefit the men. “Well”, said the men, “as you wish to benefit us, do you intend to use smaller tubs?” He replied, “No.” “Well” said the men “how then are we to know if we send an overplus to the bank?” “Oh”, said he, “gauge it with the finger”. Since the men could not get the redress they wanted, they engaged the attorney Roberts and asked to have their “get” weighed. But this was refused and so they then brought an action which was successful. Wilson said he had also worked at another colliery where he got 12 shillings for 57 hours work and when asked his employer if it was right for sober industrious men to have to slave so many hours for such a pittance, the master allowed another 6 shillings per fortnight but in order to get it back with interest he mulcted them 8 shillings 6d in fines.

In another meeting at High Holburn, Wilson declared to loud and prolonged cheering:

“By their unity they had become strong, powerful and mighty. They had neither swords or spears – theirs was metal not physical warfare – and all they asked or required was a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s labour.”

At Whitechapel, he said he had found the warmest sympathy among the men and the trades of London and asserted:

“The colliers were now united and resolved to continue so until victory crowned their efforts…the workmen were the masterpiece of machinery; they knew they possessed the power of laying all other machinery still and were resolved to use that power, unless they received a fair remuneration for their labour.”

He poured scorn on the stories of miners returning to work saying those who were going to work were blacksmiths, screeners, chimney sweeps and children out of the workhouses who were getting 4 shillings and a quart of beer a day.

At the end of July, Wilson was back in County Durham to speak at a meeting of 10,000 miners at the Batts, Bishop Auckland:

“…the meeting was addressed by some of the most intelligent and energetic advocates of the miners’ rights. Messrs. J. Wilson, J. Fawcett, R. Archer, G. Charlton, G. Emmerson, J. Beaston, N. Heslop and M. Dent.”

In August, he was at Stratford, telling how miners were on strike, “to resist the aggressive attack of their merciless employers”.

When the strike began to crumble, he was speaking at Tottenham Court Road and told his audience:

“…for the lack of support they had been compelled reluctantly to return to their employ with their grievances unredressed.”

As events unfolded in a fashion often repeated since, the military and police were used to enforce the wishes of the “management”, a new labour force was brought in from other districts such as Wales which caused intense resentment among the disposed pitmen, enforced evictions of pitmen and their families took place on a wide scale and in face of such hostility, starvation and other deprivations, the men had little choice but to return to work. The miners’ attorney Roberts exhorted the men to turn the other cheek to provocation from the owners, the police and magistrates.

Ultimately, the strike was lost. Many of the leading advocates of this action were subsequently victimised. Many, including James Wilson, could not find work and were forced into migration. In fact, colliery owners blacklisted miners for years to come even when there was a shortage. In the 1860’s colliery owners in Durham and Northumberland agreed not to employ men who could not produce a “certificate of leave” or a “clearance paper” from their last employer.

Following the strike, the Government appointed Mr. H. Seymour Tremenheere, as Commissioner to inquire into the conditions of the populations of the mining districts including the counties of Durham and Northumberland. He toured the area discussing various matters, including working conditions, employment of children and the strike, with selected figures associated with the coal industry such as the coal owners and the colliery viewers [managers]. However, the miners themselves were totally unaware of his visit therefore were not invited to comment or take part in the Inquiry. They strongly refuted many of the Commissioner’s conclusions including:

- That they were under the influence of the Chartists and

- That the “Ranters” showed a strong disposition to violence.

James Wilson was blacklisted, could not find work in the local pits and left Evenwood to settle in Crook, some 10 miles to the north. Mr. Booth, manager of Evenwood Colliery, later claimed:

“The strike which with us lasted from November 1943 till July 1844, has cleared the district of a great many of the worst characters, who are gone to the iron works on the hills. The “Ranters” were the worst agitators at the time of the strike.”

James Wilson prospered as a grocer, becoming one of the leading citizens of this new colliery town. His obituary, published 31 years later, is provided in full, (above). He may well have been one of the “worst agitators” of the strike because he believed in the cause but to describe him as one of the “worst characters” seems to be highly inaccurate.

Seven other families from Evenwood appear to have settled in Crook after the strike. Precise reasons for their move are unknown – perhaps the usual migration in search of work. 1843 saw the opening of Woodifield Colliery and Roddymoor Colliery opened in 1844. There would have been huge demand for experienced miners in these pits regardless of their backgrounds. Two families particularly, moved in circumstances which seemed a sudden uprooting:

- William and Ester Clark: William was born at Evenwood about 1793, as were his wife Ester and children, the youngest about 1843. They family left Evenwood and settled in Crook by 1851, even though he was in his 50’s at the time. They lived at White Lea Square, north of Crook to the west of Billy Row and in near proximity to Roddymoor Colliery.

- John and Phoebe Wilson: John was born at Evenwood about 1811, as were his children between 1836 and 1844, but the next child was born at St. Helen’s Auckland about 1845 and by 1848 they were in Crook, living at no.18 Woodifield Colliery.

Particular economic circumstances of some localities must have influenced family relocation. An example is that of Cockfield, a village neighbouring Evenwood where coal mining was well established pre-1830, and where the population fell by about a third, 34.9% between 1841 and 1851. 11 families moved to Crook.

The Yearly Bond was finally abolished in 1869.

Above: Mr. W.P. Roberts appears on the Durham Miners’ Association

Monkwearmouth Lodge Banner in tribute to his work on the abolition of the Bond in 1869.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

John Smith, former lecturer, Durham University Department of Adult and Continuing Education. He led a series of evening classes in Evenwood, c.1986-1994 and introduced us to James Wilson who featured in our book, “Evenwood and the Barony in 1851”, published 1990. I believe that John Smith wrote an article about James Wilson which was originally published in the journal of the Durham County Local History Society. The referenced work is with the ERDHS papers in the Randolph Community Centre and is available to be viewed upon request.

Mrs. J.D. Turnbull (Crook) and Christine Bennett (Bishop Auckland) for providing a copy of “The Primitive Methodist Church, Crook Jubilee 1868-1918 Souvenir Handbook”, “The PMC Crook Centenary Souvenir Handbook 1822-1922” and “The Story of Fifty Years of Crook Co-operative Society 1865-1915” 1916 E. Lloyd.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

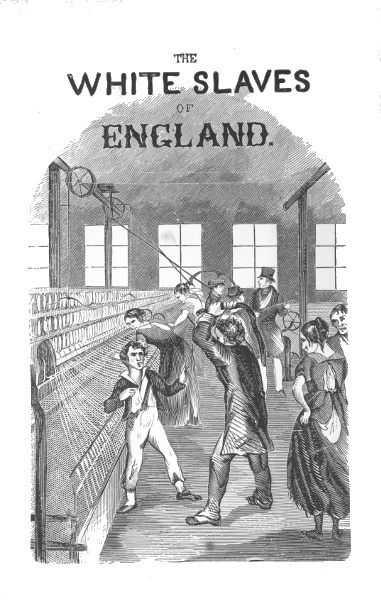

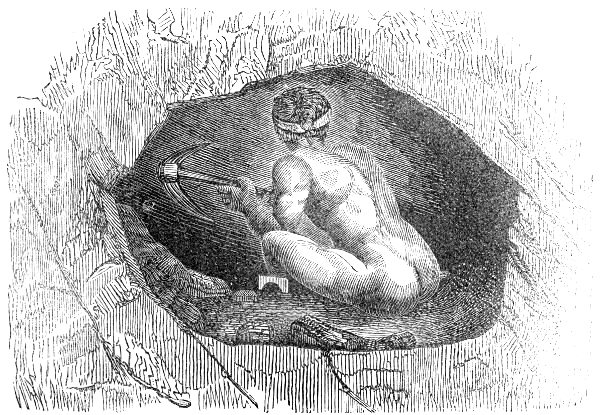

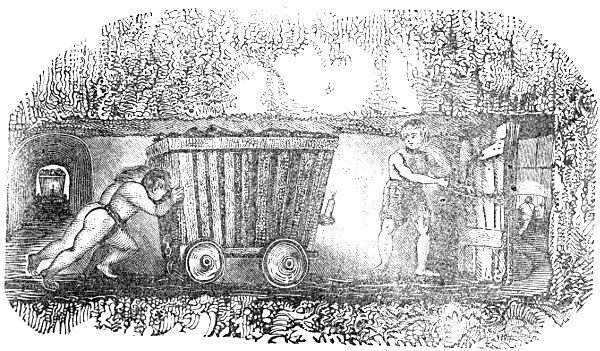

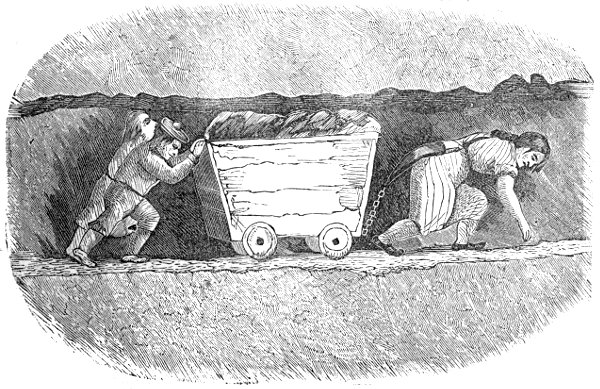

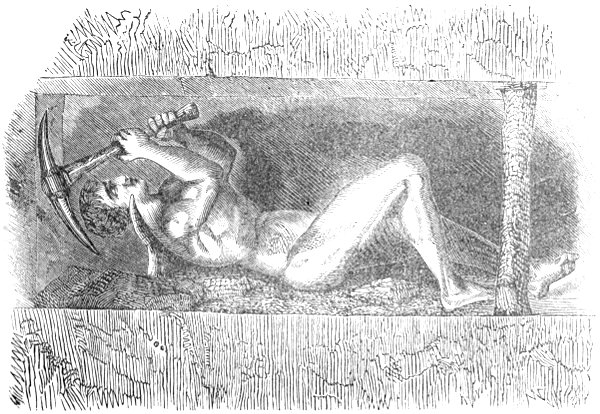

1854: “The White Slaves of England” Cobden John C., a book published in the USA compiled from official documents, included the following illustrations: