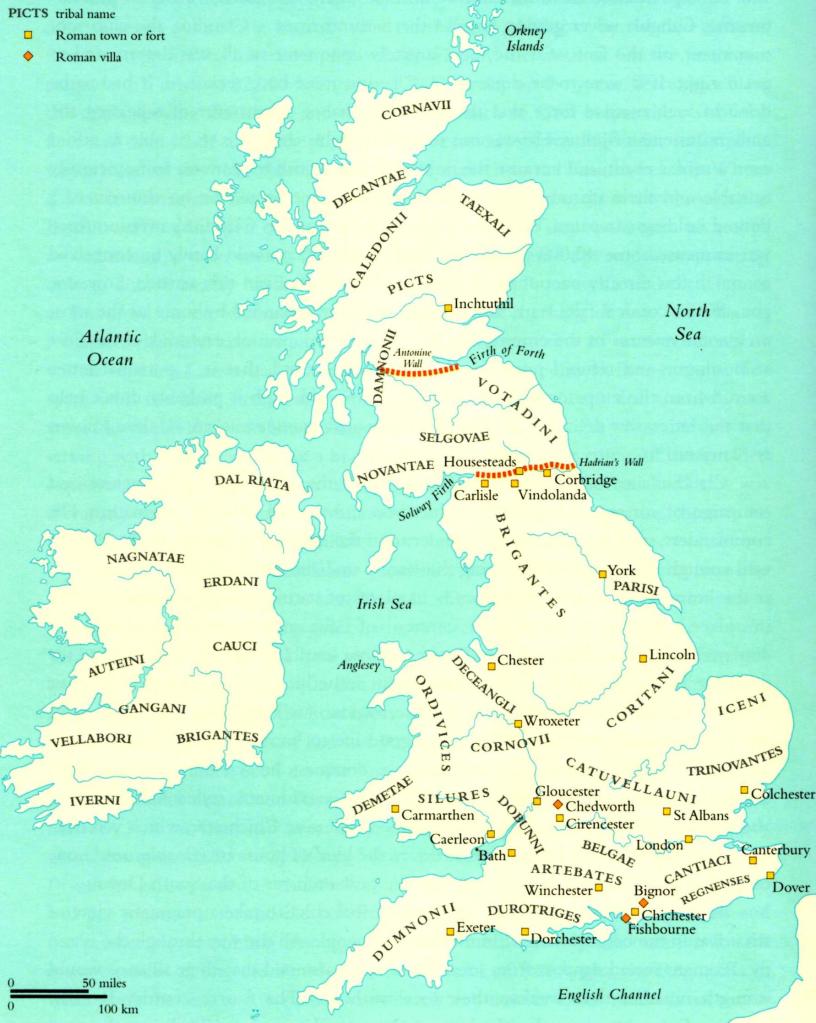

AD 43: The Romans arrived in Britain and reached the north of their province of Britannia by about AD 79. They needed to control what they called, “the barbarian tribes” that occupied the country. In the north of what we now call England, the Brigante tribe ruled the area. If persuasion wasn’t successful, then force was used.

In AD 79, following a decisive victory at Stanwick,[1] near Aldborough St. John, the Romans secured complete control of the Brigantian territory. In order to maintain control, they occupied the land by using a series of forts to garrison their armies which were connected by a network of roads. The Romans regarded the area north of York as a frontier zone, a military area required to protect the richer farmlands to the south. The most dominant feature in the north was Hadrian’s Wall which stretched 80 miles, from the east coast at Arbeia to the west coast, Luguvallium. It was designed to keep the Caledonian tribes (the Picts) out of “the south.” The remains of Hadrian’s Wall are now designated as a World Heritage Site.

MAP 1: ROMAN BRITAIN INCLUDING HADRIAN’S WALL

MAP 2: NORTHERN BRITAIN TO SHOW DERE STREET (Blue) LEADING TO HADRIAN’S WALL

A GENERAL VIEW OF HADRIAN’S WALL

The most important route to supply the Roman Army garrisoned on Hadrian’s Wall was called, “Dere Street” which led northwards from York (Eboracum) to Corbridge (Coria or Corstopitum). The road carried onwards into land occupied by the Caledonian tribes, up to the Antonine Wall, the most northerly part of the Roman Empire. Dere Street connected forts at Piercebridge (Morbium), Binchester (Vinovia) and Lanchester (Longovicium) in modern day County Durham.

Above: A Roman road at Vinovia

Sections of this road are highly visible and the route is still used today, some 1900+ years later. The straight road from Bishop Auckland town centre down through Cockton Hill and beyond up to Brusselton (unmade) then onto Royal Oak and Piercebridge is of Roman origin. The A68, travelling north from West Auckland to Corbridge and beyond is another “Roman Road.”

MAP 3: IRON AGE & ROMAN FEATURES[2]

A significant route went westwards from Bowes over Stainmore to Broughton near Penrith which linked the forts at Bowes and Binchester. Travelling eastwards, this road crossed the River Tees at Barnard Castle by a ford and ran through what we now call, Streatlam Park, Raby Castle Park, West Auckland and Bishop Auckland into Binchester.

The nearest forts to Evenwood are:

- Binchester (Vinovia)

- Piercebridge (Morbium)

- Bowes (Lavatrae)

Binchester (Vinovia) [3]

Vinovia was one of a number of military complexes built as part of Governor Agricola’s push into Scotland in the late 1st Century AD and later consolidated to support the defences at Hadrian’s Wall. The fort is situated on a hill top overlooking the place where Dere Street crosses the River Wear on route from York to Corbridge. It was a central point for road communications on the north eastern flank of the frontier zone, as it is also where the route from Bowes to Chester-le-Street and South Shields crosses Dere Street. The fort was built to guard the roads and river crossing.

Initially, it was constructed of timber around AD80 and replaced by a larger stone fort in the early 2nd Century AD. The fort was defended by a substantial stone wall with 4 gateways flanked by guard towers within a huge V shaped ditch. Inside was the HQ building, the commandant’s house, the hospital, granaries, workshops, barracks and stables. The Roman fort became a focus of local activity and a large civilian settlement (vicus) grew around it which provided for the needs of the troops and became a market centre for the surrounding area. The fort was abandoned by the Romans about AD410.

Above: Binchester (Vinovia)

By AD500 much of the fort had been demolished and at some time during the Middle Ages, a large area overlooking the River Wear was destroyed by a landslide. Today, only the excavated building and earthwork remains of the north eastern ramparts survive.

The site contains one of the best preserved bath houses in Britain.

Above: Binchester (Vinovia) remains of the bath house.

The site is a Scheduled Ancient Monument (DU 23).

In 2008, Time Team[4] was invited to Binchester, to excavate part of the fort. There was a major discovery of a series of mausolea, the first of their kind to be found in the UK for 150 years. The link for the TV programme is:

A copy of the Wessex Archaeology report is available to view t the Randolph Centre upon request.

Piercebridge (Morbium)

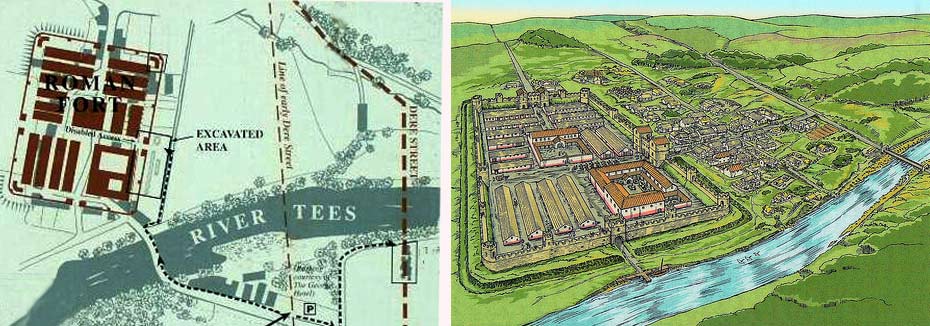

There may have been a fort here in AD70 beside the ford across the River Tees. The later Morbium fort was built about AD270 and was rectangular in shape with towers at each corner. In the centre of the north and south walls were gates through which Dere Street would have passed. The fort was abandoned in the early 5th Century AD. Part of the fort is on display to the public. English Heritage supervises the site.

Above: Piercebridge (Morbium) A map and illustration of the fort and the 2 bridges[5]

Above: Piercebridge (Morbium) the fort

The remains at Piercebridge include evidence of 2 bridges that carried Roman roads across the river [6] and an earlier prehistoric bridge. There have been a series of archaeological excavations over the years and the bridge over the Tees has been subject to specific research. [7] Bridges took an important symbolic meaning and ritual offerings were often made to the Gods by those crossing over the bridge. Since 1987, 2 local divers Bob Middlemass and Rolfe Mitchinson, have recovered approximately 5,000 Roman objects from the riverbed at Piercebridge.[8] Analysis of about 3,600 objects has taken place and a book has been published, “Bridge over Troubled Water: The Roman finds from the River Tees at Piercebridge in context” by H. Eckardt & P. Walton (2021).[9] A copy, downloaded from the internet, can be viewed at the Randolph Centre, upon request.

Above: A montage of finds from the river

In 2010, Time Team (series 17, episode 3) undertook an examination of the bridge sites. The link is:

https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x628ff3

Bowes (Lavatrae)

Covering 4 acres, the Roman fort of Lavatrea can be traced for most of its perimeter. The fort was constructed to guard the strategic route known as the Stainmore Pass and was occupied from the late 1st Century AD to the late 4th Century. It is beneath Bowes Castle which was built between 1171 and 1187 by Henry II. It is another English Heritage site.[10]

The Roman Army need to be supplied with goods, food and entertainment. Small towns grew up outside the walls of the forts, called “Vici” and much evidence of the vici was found by the Time Team excavations at Vinovia.

Romans built their towns on a regular street pattern using stone, bricks and clay tiles for important public buildings such as town halls and theatres. Rectangular shaped buildings appeared for the first time in Britain. Large high status villas were constructed in the countryside for men of importance and their families and servants.

Life for the native Britons, outside the Roman towns and forts would have carried on pretty much as before. The indigenous peoples were mainly farmers raising cattle and growing cereals and root crops as the seasons allowed but they were expected to pay taxes to the Romans. Evidence of farm sites can be seen on Cockfield Fell and at Cowley and Brecon Hill near Butterknowle. Aerial photos show other sites at Copeland House, East Park Farm and Bolton Garth Farm.

AD 410: The Romans left Britain.

SOME OBSERVATIONS (11)

Roman rule in Britain lasted about 350 years from AD 43 to 410, that is to say it endured for a span as long as Shakespeare’s time to ours, now.

Population

A generation ago, Roman Britain was believed to have a thinly inhabited population of about 1 to 1½ million people and much of the country was thought to be hardly settled. However, contemporary opinion significantly increases the estimate to 3 or 4 million.

The Economy

There are 3 important factors:

- Coins – The abundance of finds is evidence that the Romans in Britain oversaw an economy with a capacity to make money.

- Pottery – By the 4th Century, Roman Britain was self-sufficient in the production of pottery goods for ordinary use. In the early part of its rule, there was dependence on colossal imports.

- Roads – A good road network existed which was required to move goods and the military around the occupied outpost of its empire. It is beyond doubt that Roman Britain had better roads than medieval England.

Important Britons

No Briton seemed to have attained powerful office. Men from other provinces commanded and ruled Britain. Britons did not command or rule other provinces. There are only 2 British inhabitants of Roman Britain to have won lasting fame.

- Pelagius – a Christian teacher who went to Rome to study law about 380. His essential doctrine was that salvation could be achieved by man’s own efforts rather than grace.

- Patrick – the son of landowner who, at the age of 16, was captured by Irish raiders, escaped and returned to be its bishop and evangelist.

Enemies

There were foreign enemies – the Picts, the Scots and the Saxons and it seems that their combined assaults began to bring success by about 367. Roman forces in Britain numbered about 50,000.

- The Picts were inhabitants of modern Scotland, north of the Forth-Clyde line. The value of Hadrian’s Wall must have been against these people even though it is some distance from their main southern frontier, the Antonine Wall. The Picts were also sea raiders and attacked the eastern coast.

- The Scots, were inhabitants of Ireland who started to raid Britain about the end of the 3rd Century, making settlements in Wales.

- The Saxons were inhabitants of the north German plain between the Rivers Elbe and Weser and the southern part of the Danish peninsula. They probably started their assaults of the coastal areas of Britain and other areas of the Empire in the early 3rd Century.

In 383, Magnus Maximus, the commander of Britain, took away many troops to make a bid for the Empire. Britain was regarded as expendable.

Who Took Power After 410?

It is hard to tell who held authority in Britain or who were the unknown men who took power? The period 400 – 600 is often referred to as, the lost centuries. Eventually, Britain, or what we would now call England, was divided into two distinct areas:

- British west, forming part of a Christian Celtic world around the Irish Sea

- An Anglo-Saxon east, forming a pagan North Sea world. The term Anglo-Saxon is commonly used to relate to all or any of the German peoples who settle in Britain. Later, they were to be called English.

All British kings were Christian and all Anglo-Saxon kings were pagan until St. Augustine’s mission of 597 led to their conversion.

Two priests, Gildas in his work, “On the Fall of Britain” about 550 and Bede, “Ecclesiastical History of the English People” 731 offer their views on the period. Bede’s other major work was, “Lives of the Abbots.” Bede (673-735) provides a list of some powerful Anglo-Saxons kings and their lands:

- Aelle of Sussex, late 5th century?

- Caewlin of Wessex c.560-591

- Aethelbert of Kent 560-616

- Redwald of East Anglia c.616-627

- Edwin of Northumbria 616-633

- Oswald of Northumbria 634-642

- Oswy of Northumbria 642-670

Bede spent nearly all his life in the twin monasteries of Monkwearmouth and Jarrow.

Go to Evenwood in Medieval England (which will be posted soon)

REFERENCES

[1] https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1016199?section=official-list-entry

[2] “An Historical Atlas of County Durham”1992 Durham County Local History Society p.13

[3] “Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results.” Wessex Archaeology (May 2008)

[4] Time Team was a very popular Channel 4 archaeology programme presented by Tony Robinson which aired from January 1994 to September 2014.

[5] English Heritage

[6] https://www.ecastles.co.uk/piercebridgefort.html

[7] https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/piercebridge-roman-bridge/history/description/

[8] https://www.culturednortheast.co.uk/2022/02/01/roman-discoveries-up-for-national-award/

[9] https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/romanpiercebridge_lt_2021/index.cfm

[10] https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/bowes-castle/history/

[11] The Anglo-Saxons” 1982 J. Campbell, E. John, P. Wormald edited by J. Campbell various pages, mainly in Chapter 1, The End of Roman Britain.