EVENWOOD IN PREHISTORIC TIMES

The definition of prehistory is the time before written records. In Britain, written records were introduced during the Roman occupation, therefore prehistory is the huge span of time before the arrival of the Romans in AD43.

Prehistory is divided into:

- The Stone Age, subdivided:

- Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age)

- Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age)

- Neolithic (New Stone Age)

- The Bronze Age

- The Iron Age

The Stone Age is so named because the people used stone tools such as flint arrowheads and polished stone axe heads. There are few remains other than these tools. Their materials were biodegradable and rotted away and many sites have been destroyed by later development. These people were hunter gatherers and survived on food that they could collect (nuts and berries), fish they caught and meat from animals they hunted. Animal skins were used for clothing and shelter. They were nomadic, moving from camp to camp within their territory, depending upon the seasons and availability of food. The first farmers lived in the Neolithic period and they grew crops and bred animals. Monuments such as long barrows and henges began to appear at this time.

The Bronze Age is so named because metals tools were used, being better than the stone implements. Farming continued as before. Monuments such as standing stones, round barrows or cysts used for burial, appeared during this era. Stones were often decorated with cup and ring marks.

The Iron Age saw the use of iron in metal production. Although requiring a higher temperature for smelting and to forge the material, iron tools were much stronger than bronze and it proved worthwhile to produce such implements. The Brigantes tribe ruled the north and an example of their earthwork camps can be found at Stanwick, North Yorkshire.

The Brigantes [1]

The Brigantes controlled much of northern Britain when the Romans arrived in AD 43. In exchange for their independence their queen, Cartimandua, agreed to co-operate with the Romans. The treaties were not accepted by the whole tribe, however, and a power struggle between the different factions followed. The Brigantes’ occupation of Stanwick was concentrated on the area known as the Tofts, to the south of the church of St John the Baptist. Ramparts were built around the original settlement. Excavation here has revealed timber roundhouses and other structures dating from the middle of the 1st century AD. Pottery and other finds show that during the reign of Cartimandua, the Brigantes at Stanwick enjoyed access to luxury goods imported from other areas of the Roman Empire. Excavated items include amphora jars for storing wine, ceramics from southern France and the Rhineland and German and Italian glass.

As the site developed rapidly into an important trading post and a major centre of Brigantian power, the ramparts were extended. Although Stanwick flourished for several decades during the 1st century, it declined in importance after AD 70 when Roman power and influence expanded northwards.

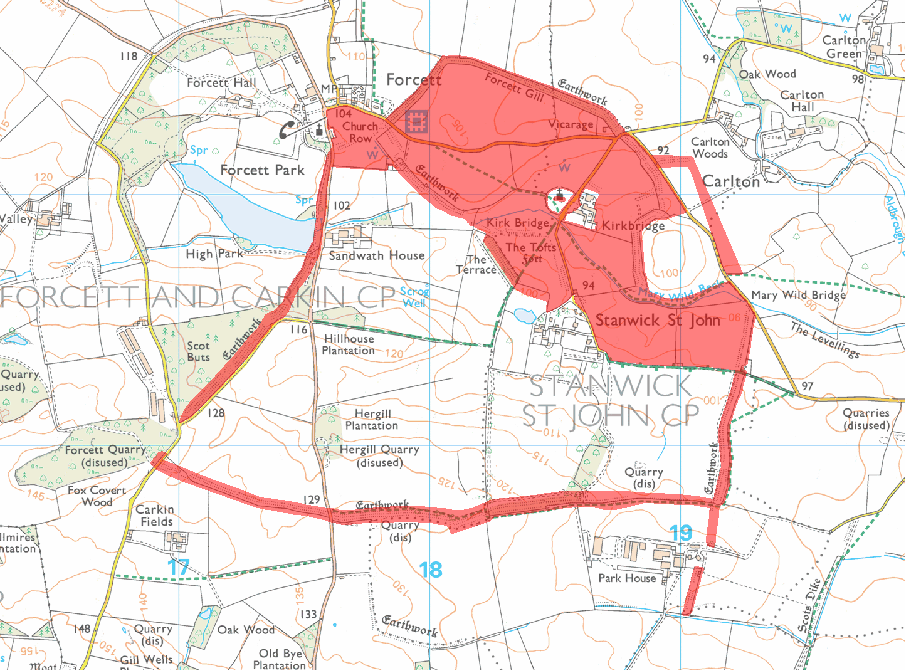

Stanwick, North Yorkshire [2]

The Stanwick “late” Iron Age hillfort, also known as Stanwick Camp, lies some 8 miles to the north of Richmond, north Yorkshire, covering a large area of more than 700 acres and up to 5 miles in length, north of the village of Stanwick St John, with the earthworks spreading out from the hillfort itself.

Above: A Map to show Stanwick Camp

The hillfort or oppidum was built by the Brigantes tribe of northern England in three different phases roughly between 47-72 AD, with the first phase of the fort being at Toft Hill. The Brigantian leader Venutius, husband of Queen Cartimandua, was “thought” to have been defeated and killed by Roman troops from York at Stanwick in 74 AD – at about the same time that parts of the fort were destroyed by fire, but the fire was ‘probably not started by the Romans’ – although Quintus Petillius Cerialis, who was Roman Governor of Britain (71–74 AD), might have had a hand in that destruction at some point.

A description of the Stanwick site states:

“If not the most impressive to view, this fortified area is the largest and greatest engineering feat of the Iron Age tribes. It started as a 17-acre (6.9-ha) fort in the early 1st century AD, and was twice extended until the fortification enclosed no less than 747 acres (302 ha). It is believed to have been the rallying-point of the Brigantes under their king Venutius who revolted against the Emperor Vespasian in AD 69. His queen, Cartimandua, had taken the side of the Romans and may have set up her headquarters at the fort at Almondbury near Huddersfield.

“In about AD 50-60 (after the Roman conquest of the S of Britain) another 130 acres (53 ha) to the N of the fort were enclosed by a bank and ditch except on the SE where a stream, the Mary Wild Beck, acted as a barrier. The fortifications between the old and new sections were demolished. Part of this bank and ditch have now been restored.

“The final huge extension covering some 600 acres (243 ha) was made to the S of the Beck and brought into the fortified area a rough quadrilateral of land capable of accommodating an army and pasturing horses and cattle. It was enclosed within a bank and ditch with an in-turned entrance on the S. There are signs that the fortifications were attacked by the Roman commander Cerialis before this section was completed. Part of the ramparts then appear to have been deliberately destroyed. No account of this campaign has ever been found, but the fall of Stanwick opened the way to the N for the Roman armies.”[3]

The Stanwick Hoard [4]

In 1845 a hoard of 140 metal artefacts known as the Stanwick Hoard, which included four sets of horse harness for chariots and a bronze horse head ‘bucket attachment’, was found half a mile away at Melsonby. The hoard is now held by the British Museum, which also has the Meyrick Helmet, which may have been part of the hoard or have been made at Stanwick.

Above: Horse’s-head plaque,

Stanwick By Johnbod – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11522642

Above: The Meyrick Helmet, thought to have been part of the Stanwick Hoard or have been made at Stanwick.

Stanhope

The most significant Bronze Age discovery made in Britain was at Heatheryburn Cave, Stanhope. The large hoard of high status actefacts are kept at the British Museum.

Above: Part of the Heatheryburn Hoard

Local evidence of other prehistoric sites:

Evenwood

The earliest evidence of occupation dates from the Mesolithic period (Middle Stone Age). A tiny flint (called a microlith) was found in the present day village. Flints from the Bronze Age have also been discovered. By the end of the Iron Age, the local landscape may have been small fields amongst which stood farmsteads surrounded by a palisade and a ditch.

Hummerbeck, West Auckland

A Bronze Age round barrow has been identified by aerial photographs. This would have contained a single burial.

Toft Hill and South Church

They were both locations for Iron Age hill forts.

Cockfield Fell

Cockfield Fell comprising 237.5 ha (586.88 acres) constitutes England’s largest Scheduled Ancient Monument described as:

“One of the most important early industrial landscapes in Britain.” [5]

And

“An incomparable association of field monuments relating to iron age settlement history and industrial evolution of a northern English County.” [6]

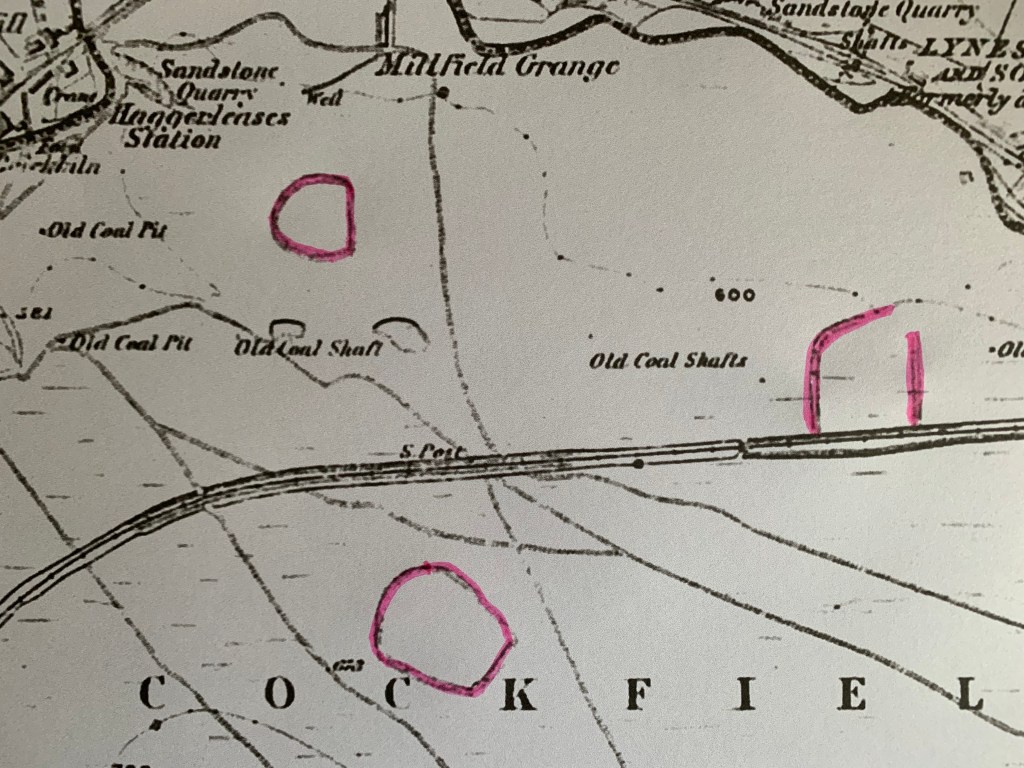

The 3 banked and ditched enclosures (see plans) are probably of Romano-British date.[7] Other sources state that:

“There are 3 notable prehistoric enclosed settlement sites within the north-western part of Cockfield Fell that seem to have been built for farming rather than as defensive enclosures.” [8]

Historic England provides little information on its website.

Another website states that the area is 350 ha (850+ acres) and:

“There are traces of human activity here (in the shape of flint arrowheads) stretching back 10,000 years; and there is clear evidence of pre-Roman occupation, too, by way of at least four Iron Age settlement enclosures. A rectangular-shaped earthwork may, it is thought, be Roman.”

It concludes:

“If ever there was a place ripe for further archaeological examination it is Cockfield Fell…” [9]

Above: A detail of Cockfield Fell as illustrated by the First Edition of the Ordnance Survey map, published 1859. Edged in red are the 3 enclosures referred to above. Are they pre-historic or Romano-British features?

The 1924 OS sheet shows the possibility of a 4th enclosure. The notation, “Camp” is used and the 4th enclosure is located to the east of the others – to the south of the quarry, between the L and D of COCKFIELD.

Above: A Detail from the 1924OS Sheet

This plan also shows the industrial development that took place on the Fell – this will be discussed elsewhere.

[1] https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/stanwick-iron-age-fortifications/history/

[2] https://thejournalofantiquities.com/2017/01/26/stanwick-iron-age-hillfort-north-yorkshire/

[3] “The Observer’s Book of Ancient and Roman Britain” 1976 H. Priestley

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanwick_Iron_Age_Fortifications

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cockfield,_County_Durham

[6] “West Durham: the archaeology of industry.” 2008 Guy & Atkinson

[7] https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/common-land-in-britain/cockfield-fell-co-durham/A19BCD336918D3A347D8CB081FD7E376

[8] https://englandsnortheast.co.uk/west-auckland-gaunless-valley/

[9] https://northeasthistorytour.blogspot.com/2016/10/cockfield-fell-nz120250.html