The trade union was formed in 1869 with a membership of about 4,000. This followed 2 previous attempts for the Durham pitmen to organise themselves in an attempt to improve their conditions at work and socially. These actions of 1832 and 1844 both failed.

1830 – 31: Thomas Hepburn formed the Northern Pitman’s Union, dubbed, “Hepburn’s Union”. There was a strike in 1832. At this time, the main issues affecting the pitmen were the length of the working day and their method of payment. The union won concessions in that the working day was reduced from 18 to 12 hours and their wages were to be paid in money rather than tokens for use in the company’s “Tommy Shop”. The response of the coal owners was to refuse to employ workers who were members of the union. This resulted in the strike of 1832 which was bitter and violent at times. Pitmen were starved back to work, their leaders were blacklisted and the union was outlawed. Ultimately, this industrial action saw the collapse of the union and Hepburn was blacklisted. He eventually found work at Felling Colliery on the understanding that he would not involve himself in union activities. Suffering from ill health, Hepburn ceased working in 1859 and died in 1864 aged 69.

Thomas Hepburn 1795 – 1864

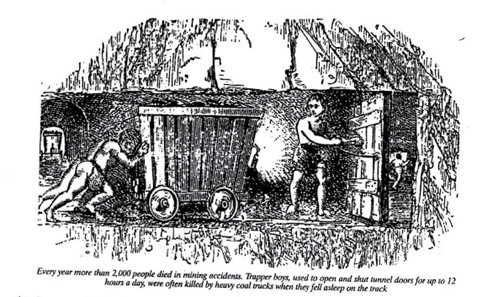

Even though reduced hours were won, young trapper boys, tending the ventilation doors, would still sit in the dark for 12 hours or more. Not until the Coal Mines Act of 1842 was underground employment of women and children under the age of 10 prohibited.

1844

The second was the strike of 1844. The most significant grievance was the way in which pitman were hired – the Yearly Bond. Similar to farm workers, pitmen were hired by a colliery owner on a yearly basis and they had to sign the bond. An explanation of the Bond is given below:

“The annual bond in Northumberland and Durham had its origins in the traditional method of binding farm servants and labourers and the signing ceremony was in many areas, accompanied by a feast day comparable to the hiring fairs in rural districts. Reflecting its agricultural origins, the colliers’ bond ran originally from autumn to autumn, but as this caused a hitch in production at a time of peak sales of coal, the term was altered in 1812 to run from April to April.

Initially, it was the custom for the clauses of the bond to be read out before the colliers signed it, but this could take some time since by the 1830’s the document had increased in complexity and could be several thousands of words long, including details of payment, instructions on methods of working, colliery regulations, and where colliery housing was provided, as was usual in the north‐east, conditions of tenancy. (Glass to be kept in good repair, fourteen days to get out if employment ceased, no dogs to be kept, were typical conditions). It even contained a provision for arbitration in the case of disputes.

The bond was couched in such legal language, which submerged itself from time to time into reams of dependant clauses that it can have meant little to those literate colliers able to read it at leisure, and must have meant even less to those who heard it gabbled at top speed. An official present at one signing questioned some of the colliers about the bond and, “scarcely one of the witnesses whom I examined could give any outline of the provisions of the agreement to which they had thus formally consented, though well acquainted with the bearing of some stipulations which they considered grievances”.

‘Signing’ was something of a misnomer, because, regardless of whether a collier could sign his name in script, it had become the practice, for the sake of speed, to make a mark. The same official reported, “I observed more than one hundred persons indicate their assent and signature by stretching their hands over the shoulder of the agent and touching the top of his pen while he was affixing the cross to their names, and this, I was told, was a common practice”.

Although the bond gave colliers a measure of security and even contained in some instances, provisions for short time working, or what would today be called a guaranteed working week, it had a number of drawbacks. Because the demand for labour was variable – a cold snap in London, the north‐east’s main market, or the not infrequent sinking of a London bound coaster could result in an unexpected leap in demand – extra short term help was obtained by taking on unbound men, who might be migrants or men whom former employers had refused to sign again.

In Durham, in 1841, it was that as much as one quarter of the collier workforce was “floating”. Although the unbound men were subject to the same conditions as those who had signed the bond, there was always the suspicion that they might, in the event of a dispute, work on regardless or accept a lower rate for the job. Indeed, this often happened, and here lies the germ of the blackleg problem for which the Northumberland and Durham coalfield was, in the latter half of the 19th century to become notorious.

The bond was a legal document, and a man who broke its terms laid himself open to fines, dismissal, or, if he left his place of work before he had worked out his time, a term in prison. In the South Durham district in the year 1839 – 40, 172 men spent periods in Durham jail for various bond offences. Not being under these constraints, the unbound men were resented and so the bond became associated with the beginnings of trade union activity, sporadic though this was.

The disadvantage of the annual bond from the points of view of both employer and employed, was that it focussed the heat of negotiations on one month or less in the year. Until 1812, the autumn signings gave the colliers an advantage, since the pressure of demand was an incentive for the masters to settle. After 1812, with the spring signing, the advantage switched; the masters could bear with a dispute during the quiet summer months. But, either way, the signing of the bond became an occasion for on the one hand, a tightening of the screws on colliers, or, on the other, the rehearsal of old and new grievances.”

Such was the system of hiring pitmen, with most men signing their contract with a cross since they could not read or write. Often they had not heard or understood the terms of the bond. Fines were imposed for trivial transgressions and with the bond backed up by the law, the threat of imprisonment was constant. The men considered that this system needed to change and allied with the reduction in wages, the time had come to take action.

This was when James Wilson, an Evenwood pitman, came to the attention of the public. He was selected as an advocate for the miners’ cause. Their case was misrepresented in the press, so the leading members of the Durham and Northumberland miners, chose 12 “practical pitmen” to go to London and address the general public at pre-arranged meetings, in order to seek support. They became known as the “Twelve Apostles”.

James Wilson 1819 – 1875

They appointed W. P. Roberts, a Chartist solicitor, from Bristol, as their “Attorney General”. The Chartist movement was the first mass movement driven by the working classes. It grew following the failure of the 1832 Reform Act to extend the vote beyond those owning property. In 1838. a People’s Charter was drawn up for the London Working Men’s Association (LWMA) by William Lovett and Francis Place, two self-educated radicals, in consultation with other members of LWMA. The Charter had six demands:

- All men to have the vote (universal manhood suffrage)

- Voting should take place by secret ballot

- Parliamentary elections every year, not once every five years

- Constituencies should be of equal size

- Members of Parliament should be paid

- The property qualification for becoming a Member of Parliament should be abolished.

However, this industrial action was lost. Many of the pitmen’s leaders were subsequently victimised, including James Wilson. They could not find work locally and were forced into migration. A fuller account of this action and the life of James Wilson can be found at:

1869: The formation of the DMA

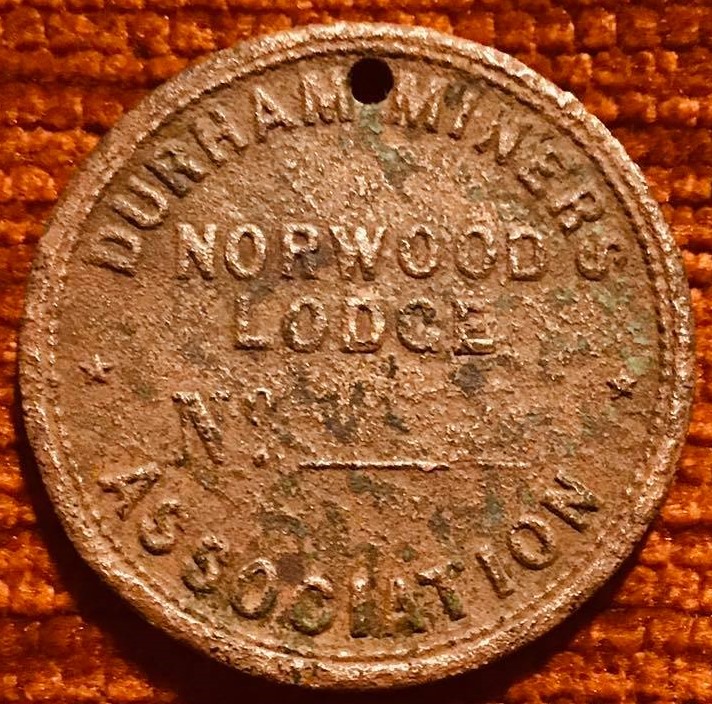

The Durham Miners’ Association held its first meeting in the Market Hotel, Durham on the 20 November 1869. In March 1870, there were delegates from 28 collieries representing 3650 members. But there was a gradual fall in membership and by May 1870, there were 22 lodges with 2172 members, Evenwood having 63 and Norwood 33. The largest lodge was Murton with 342 members. The first annual gala was held in Wharton Park, Durham 12 August 1871.

Progress had been made with working practises within the coal mining industry:

- 1869: The miners’ advocate Mr. Roberts succeeded in challenging the authority of the Bond in the Courts and won the case but it was not until 17 February 1872 that the practice was abolished in Durham.

- 1872: The Mines Act enforced a ban on boys under the age of 12 from working underground

Prior to 1872, pitmen in Durham were “bound” to the colliery and whatever terms the colliery owners demanded, enforced by law. It may not have been “slavery” as we understand the word today but it was an unjust practice. For the record, Britain abolished slavery in the Great Britain in 1807 and the Empire in 1833. The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 freed more than 800,000 enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and South Africa and a small number in Canada. It took effect 1 August 1834. Slave owners received £20 million in compensation, which represented 40% of the government’s total annual expenditure. Apparently, £20 million in 1833 is worth £2,184,631,578.95 in 2016.

Below: DMA Wearmouth Banner celebrating the cancelling of the yearly bond by Mr Roberts in 1869.

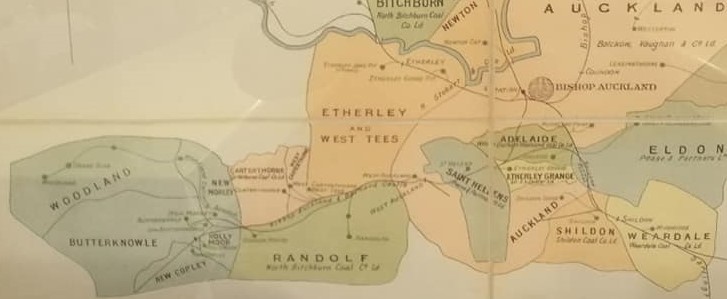

Below: 1872: Miners Lodges

The map names West Auckland, Tindale Crescent and St. Helens lodges and others are indicated in the Gaunless Valley area.

By 1872, there were 2860 members in the Auckland District including 1310 members from lodges in the Gaunless Valley area. Membership figures were:

Evenwood 140

Norwood 100

Railey Fell 100

Lands (Cockfield Fell) 60

Butterknowle 120

Carterthorne 90

Tindale & St. Helens 250

West Auckland 230

Woodhouse Close 220

Perhaps, the smaller pits and drifts were not unionised at this time. Was Woodland Colliery working at this time?

During the late 19th century, there were peaks and troughs in the coal industry. Job security and wages was a constant issue between the men and the owners. Industrial action was common both locally at individual collieries and countywide.

In 1874, a strike began the process of agreeing wages across the county.

In 1890, action ensured that the Durham area adopted the standard of the 7-hour day, the first in the Great Britain.

In 1892, action prevented a proposed 15% cut in wages – 10% was agreed.

In 1892, the DMA was affiliated to the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) but was expelled the following year for not joining a national strike of 1893.

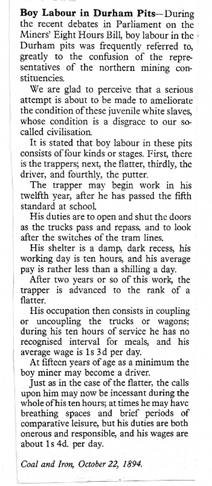

1894: The Miners’ Eight Hours Bill was introduced in Parliament. An article from the “Coal and Iron” magazine 22 October 1894, describes the work of boys in the Durham pits.

In 1900, the Mines Act raised the age limit to 13 for boys working underground.

In 1911, the age limit was raised to 14.

William House (1854-1917)

A prominent local politician was William House, raised and worked at West Auckland. Between 1900 and 1917, he was President of the DMA, a position he held until his death. He was succeeded by James Robson. William House was also vice-president of the MFGB between 1914 and 1917, being succeeded by Herbert Smith.

In 1908, the DMA re-joined the MFGB. Its membership was about 80,000.

By 1912, industrial relations between the men and the owners were poor. There was a national strike ballot which had a 42,000 majority for strike action but the 2/3rds majority was not secured. The strike did not take place. In Durham, there was a 24,000 majority for action but locally, the men voted for work. The votes cast were as follows:

Randolph 403 to 130

Gordon House 201 to 149

Carterthorne 32 to 6

New Copley 97 to 5

St. Helens 151 to 114

West Auckland 280 to 139

A total of 1707 votes were cast in these lodges.

COAL MINING EMPLOYMENT: 1914

The following table provides details on employment levels at the collieries and pits in the Gaunless Valley area.

| COLLIERY [LOCALITY] | TOTAL | UNDERGROUND | ABOVE GROUND |

| ST. HELENS | 696 | 508 | 188 |

| WEST AUCKLAND | 587 | 494 | 93 |

| RANDOLPH [EVENWOOD] | 1039 | 782 | 257 |

| RAILEY FELL/WEST TEES [RAMSHAW] | 250 | 204 | 46 |

| NEW MORLEY [EAST BUTTERKNOWLE] | 39 | 32 | 7 |

| GORDON HOUSE [EAST COCKFIELD] | 836 | 689 | 147 |

| LOW BUTTERKNOWLE [LOW LANDS] | 26 | 23 | 3 |

| CRAKE SCAR [EAST OF WOODLAND] | 48 | 32 | 16 |

| WOODLANDS [COWLEY & WOODLAND] | 494 | 384 | 110 |

| LANGLEYDALE [WEST OF COCKFIELD] | 42 | 39 | 3 |

| WHITE HOUSE [WEST OF WOODLAND] | STANDING | ||

| QUARRY DRIFT [BUTTERKNOWLE] | 18 | 17 | 1 |

| NEW COPLEY COLLIERY [WEST COCKFIELD] | 292 | 243 | 49 |

| CARTERTHORNE [WEST TOFT HILL] | 165 | 125 | 40 |

| WEST CARTERTHORNE COLLIERY [TOFT HILL] | 78 | 62 | 16 |

| BUTTERKNOWLE/MARSFIELD | 22 | 19 | 3 |

| BLACK HORSE [WACKERFIELD] | 49 | 45 | 4 |

| OLD NORTH END [COCKFIELD] | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 4687 | 3702 [79%] | 985 [21%] |

As can be seen, there were some 4,687 miners employed, most at Randolph, Evenwood and Gordon House, Cockfield which were worked by the North Bitchburn Coal Company and later by Pease & Partners then the Randolph Coal Co. (the Summerson Brothers). The number of men employed would increase as the demand for coal increased during the war years, 1914-18. There was a short boom in the coal industry after the war, as supplies from Belgium, France and Germany were interrupted, however, this was short lived and the difficult state of the industry returned in the 1920s. The coal industry was in decline and the north east of England was hit hard. In the 1920s, the country was in chaos:

- 1920: June – November: Miners’ strike.

- 1921: February and March: wage reductions,

- 1921: April – July, the “Lock-out” of the miners by the coal owners.

- 1926: May to November: the National Stoppage including the General Strike 3-12 May.

Around Bishop Auckland and the Gaunless Valley, there were a great many pit closures. Basically, the coal seams were nearing exhaustion and geological conditions were difficult. There was always the fear of water inundation and flooding. The cost of pumping was a great concern and, apparently, individual coal companies did not work in unison to address this issue. The collieries to the east of the county were more modern and offered more secure employment. As a result, there was a drift of pitmen from the west to the east in search of work. The DMA delegates had to address this issue amongst many others. Pit closures in the district included:

- 1920: Diamond Pit, Butterknowle

- 1924: Copley Bent; Woodland

- 1926: St. Helens Colliery; Lynesack Drift

- 1927: Carterthorne; Keverstone Grange

- 1929: Old Copley; Copley Grange

- 1930: Copley Road

- 1934: Butterknowle

- 1938: Crake Scar Colliery

- 1939: West Tees Colliery (Ramshaw and drifts at Railey Fell); West Pitts (Woodland)

In time, the union lodges closed as the larger pits closed. Small scale drift mines opened up to exploit the remaining reserves of coal in the western areas around Woodland, Butterknowle and Cockfield.

Regionally, the employment situation in the North East was not good, as the following statistics indicate:

- Between 1924 and 1935, the number of miners employed fell from 174,756 to 101,401.

- Between 1929 and 1936, output fell from 39 to 31 million tons with a 23% reduction in numbers employed.

- Between 1931 and 1935, there was a migration out of the region of no fewer than 218,000 people from Durham and 47,000 from Northumberland.

- In 1935, in England & Wales, of the 488 new factories established 213 were in Greater London and of the 182 extensions, 51 were in Greater London. There were only 2 new factories and 5 extensions were in Durham & Tyneside.

- In 1937, the unemployment rate for Bishop Auckland was 39.5%, Cockfield 37.1% and Shildon 38.8%. These were the highest 3 rates of unemployment in the North East.

- The population of Bishop Auckland declined from 44,455 in 1921 to 38,935 in 1931 and 35,493 in 1941.

Families moved elsewhere to find work. Many pitmen moved to other coalfields such as Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire. The DMA faced a situation where many collieries were in financial difficulty and the coal owners sought to reduce capacity and the men’s wages, for collieries to remain financially viable. The DMA fought to retain jobs, secure a living wage and improve safety. Nationalisation of the coal industry was seen to be the answer and the unions fought for this ideal. The Second World War, 1939-1945, saw the coal industry come under government control and there was a general belief that nationalisation would solve many of the problems. In 1947, the National Coal Board (NCB) was established to control the British coal industry. For further details, see

In 1945, the union became the Durham Area of the National Union of Mineworkers and later became known as the North East Area of the NUM. There were 3 affiliated “specialist” unions, namely the Durham County Colliery Enginemen’s Association, the Durham County Colliery Mechanics’ Association and the Durham Cokemen’s Association. They worked with the DMA as the Durham County Mining Federation Board.

In Durham, there was a realisation that only those larger collieries in the east of the county would survive. The coal seams were now being worked many miles out to sea. The pits in the west closed on an organised basis where men were relocated to other collieries, either in the county or other coalfields. Planning future development in the county was largely influenced by the decisions of the NCB. In the Gaunless Valley and the Bishop Auckland area, underground mining ceased to exist by the mid-1960s.

The DMA lodges closed as the pits closed. As an example, in June 1968, the Gordon House Lodge (DMA) was closed.

Randolph Coke Works at Evenwood was not under the control of the NCB. It was worked privately after nationalisation and operated until May 1984 when it was closed down. Its employees were, in the majority, members of the Durham Cokemen’s Association and some were members of the Durham County Colliery Mechanics’ Association.

There were major strikes in 1972, 1974 and 1984-85. The action in the 1970s saw improved pay and working conditions but the UK miners’ strike of 1984 which lasted over a year, in the long term, did not achieve its objectives of preventing colliery closures, maintaining jobs and safeguarding mining communities. In North East England, there were about 23,000 miners at the outset of the action, 19 November 1984, with 95.5% on strike.

10 December 1993: Deep mining in Durham ceased with the closure of Wearmouth Colliery, Sunderland.

December 1994: The coal industry was privatised creating R.J.B. Mining, subsequently UK Coal.

26 January 2005: The last deep mine in the North East, Ellington Colliery, Northumberland, was closed.

18 December 2015: The last deep colliery in the UK, Kellingley Colliery on the Yorkshire Coalfield, was closed, bringing an end to centuries of deep coal mining.

In 2018, the North East Area of the NUM was dissolved.

Below: There are images showing 4 DMA tokens from local lodges – Evenwood, Lands, Norwood and Railey Fell.

These tokens were issued to union members at a time when union membership was frowned upon by the colliery owners and management. DMA members they felt it necessary to keep their membership secret for fear of reprisals. The token would be shown by members at union meetings, often sown on the inside of their coat collar, using the 2 holes drilled into the token.

There is a detail from a map which identifies the areas which the colliery companies worked.

A DMA schedule which relates to the year ending 31 December 1950 and provides details of the number of union lodges, their seat number in the debating chamber and the number of votes each lodge carried. The greater the number of members, the more votes they had. There were 150 lodges and a total voting strength of 791. At this time, the DMA union delegates represented about 110,000 miners. The lodges representing miners of the Durham coastal collieries were the largest:

- Horden had 16 votes,

- Easington and Dawdon 15 each,

- Blackhall and Murton 14 each.

The lodges local to our area were:

- Brusselton 3 votes,

- Butterknowle 1,

- Etherley Dene 1,

- Etherley Jane 1,

- Gordon House 3,

- Railey Fell 1,

- Ramshaw 2,

- Randolph 3,

- West Auckland 2,

- White House 1

- Woodlands 2.

Below: A detail from the schedule

The Randolph delegate’s seat was number 108, Railey Fell was 127, Ramshaw 187 and Gordon House 118.

Below: An image of a seat is provided.

NOTE: Full references and sources of information are available on request.