William Arthur DENT 1922 – 1943

1522988 Sergeant Pilot (U/T) William Arthur Dent RAF Volunteer Reserve died 26 July 1943 aged 20. He is buried at Harare (Pioneer) Cemetery, Zimbabwe,[1] commemorated on Etherley War Memorials and on his mother’s headstone in Evenwood Cemetery.

Family Details

William Arthur Dent was born 22 December 1922, the son of Arthur and Elizabeth Annie Dent (known as “Lizzie”) at the Bridge Inn, Ramshaw near Evenwood, Bishop Auckland, County Durham.[2]

In 1921, Arthur (1896-1973) married Elizabeth Annie Thompson (1902-1945).[3] In 1911, he lived at Low Gordon Farm near Evenwood and worked as a farm hand.[4] In June 1918, Arthur enlisted into the British Army, the Guards Machine Gun Regiment, and was demobilized in February 1919.[5]

Elizabeth was born 31 August 1902[6] in South Africa, the daughter of William and Jane Thompson. In 1921, they were publicans of the Bridge Inn, at Ramshaw. Arthur and Lizzie Dent lived with them together with her 3 sisters (Florence, Maud and Mabel) and brother George. Arthur was recorded as a farmer. Florence was born in Cape Colony, South Africa c.1900, as was Lizzie c,1902, Maud c.1911 and George c.1912. Mabel was born at Evenwood about 1917 therefore the Thompson family returned to Britain sometime between 1912 and 1917.[7] Britain was at war with the Boers in South Africa between 1899 and 1902. It is hard to imagine a British subject emigrating to South Africa during this period. William Thompson may have been in the British Army at the time. Further research is required.[8]

By 1939, Elizabeth was the publican of the Cross Keys Inn at Toft Hill.[9] It seems likely that Elizabeth and Arthur divorced. He was not living with her in 1939.

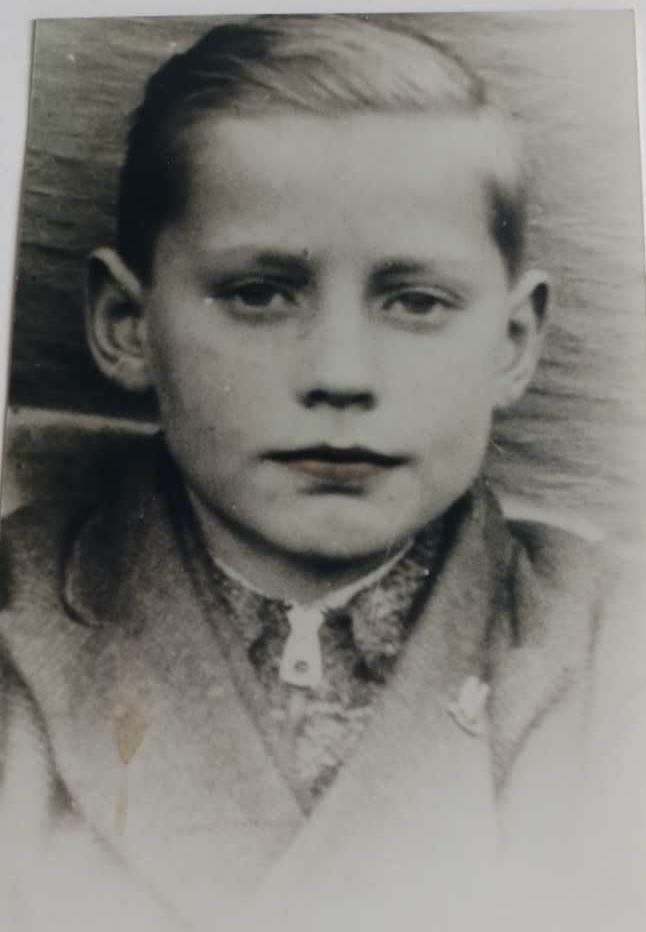

Above: William Arthur Dent aged about 10

In 1944, Elizabeth Dent married Alphonso Fryer (1909-1976)[10]. Alphonso was born at Woodland (Craik Scar) where his father worked as a coal miner.[11] In 1939, Alphonso lived with his parents, Alfred and Theresa and 4 siblings at Toft Hill. He also was employed as a coal miner. [12]

Elizabeth Fryer died 22 October 1945, aged 43 and is buried in Evenwood Cemetery. A commemoration to her son, Sergeant William Dent RAF is inscribed on her headstone.

Above: The Cross Keys Inn, Toft Hill

Above: William Arthur Dent with (believed to be) his mother Lizzie (Elizabeth Annie)

Above: William Arthur Dent with (believed to be) his fiancée (name unknown)

Service Details

The service details of 1522988 Sergeant (Pilot Under Training) William A. Dent have not been researched.

1522988 Sergeant (U/T Pilot) William Arthur Dent RAF Volunteer Reserve

Sergeant (U/T Pilot) W. A. Dent was based at Cranborne Air Station, Salisbury (now Harare), Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).[13]

26 July 1943, he and Sergeant Pilot I.T. Thomson were killed in a flying accident at Grove Farm, 19 miles northeast of Salisbury on the Mtoko road.[14] It is understood that they were flying a North American Harvard (I P5958) out of Cranborne aerodrome. To date, details of the accident have not been researched.

Further information about Southern Rhodesia’s contribution to the war effort is given below.

The Rhodesian Air Training Group (RATG) [15]

From May 1940 to March 1954, the RAF had a presence in Southern Rhodesia in the form of the Rhodesian Air Training Group (RATG) which trained aircrew for the RAF from many countries – Britain, Australia, Canada, South Africa, New Zealand, USA, Yugoslavia, Greece, France, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, Fiji and Malta as part of the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS). Air Vice-Marshall Sir Charles Warburton Meredith KBE, CB, AFC, who commanded the RATC, believed that the scheme was Southern Rhodesia’s main contribution to the WW2. The other significant contribution was that Southern Rhodesia’s 3 squadrons were transferred to the RAF and became 44, 237 and 266 Squadrons, RAF, bearing the name Rhodesia. Eventually there were 11 operating aerodromes which required a huge national effort to build, maintain and staff – at its peak, more than 1/5th of the white population was involved.

Under this scheme, some 8,235 Allied pilots, navigators, gunners, ground crew and others were trained in Southern Rhodesia, representing 5% of the total.

| COUNTRY | TRAINED AIRCREW | % |

| Canada | 116,417 | 69 |

| Australia | 23,262 | 14 |

| South Africa | 16,857 | 10 |

| Southern Rhodesia | 8,235 | 5 |

| New Zealand | 3,891 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 168,662 |

At the end of the war, the RATG was run down. The Southern Rhodesia Air Force operated as a separate unit from 28 November 1947. However, the RATG was revitalised in May 1948 as a result of the Korean War but was finally disbanded in March 1954 and training of RAF air crew reverted back to the British Isles.

A war time Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) gave a recruit 50 hours of basic flying instruction on a simple trainer, such as the De Havilland Tiger Moth. Pilot cadets who showed promise went onto training at a Service Flying Training School (SFTS) where they were awarded their “wings.” The SFTS provided intermediate and advanced training for pilots, including fighter and twin-engined aircraft, on the North American Harvard and Airspeed Oxford aeroplanes. Other trainees went onto different specialities, such as wireless, navigation, or bombing and air gunnery. The complete flying training course was estimated to last six months, with two months spent on each stage – elementary, intermediate and advanced. During this period the various ground subjects were taught and each pupil had to complete not less than 150 hours of flying. But as the scheme developed it was decided the course could be shorter and the stages were reduced to seven weeks each and a short course of night flying became part of elementary training.

The original programme of an initial training wing and six schools (Belvedere, Induna, Cranborne, Guinea Fowl, Kumalo, Thornhill) was increased to eight flying training schools (with Mount Hampden and Heany) and in addition, a bombing, navigation and gunnery school (Moffat) was opened for the training of bomb aimers, navigators and air gunners. To relieve congestion at the air stations, six relief landing grounds for landing and take-off instruction were established (Parkridge, Sebastopol, Hienzani, Nkomo, Senale, Marrony) and three air firing and bombing ranges (Mias, Myelbo and Kutanga) Later another air station was established for the training of flying instructors (Norton) and this brought the total to ten air stations.

Two aircraft and engine repair and overhaul depots were set up and a central maintenance unit to deal with bulk stores for the RATG programme.

The training aircraft used were Airspeed Oxfords, Avro Ansons, Fairey Battles, North American Harvards, De Haviland Tiger Moths and De Haviland Chipmunks and Fairchild Cornells.

The first group graduated from elementary flying training school in July 1940. By early November 1940, the first pilots to be trained by the RATG passed out at Cranborne air station, 5 of whom were Rhodesians.

No.20 Service Flying Training School (SFTS) Cranborne

Originally a flying school known as Hillside but renamed Cranborne in 1939, it was located 5 kilometres from the city centre. From July 1940 to September 1945, its role was as a SFTS, as part of the RATG. In late 1940, it was decided that Cranborne and Thornhill would be used to train single-engined pilots, or fighter-pilots, and Kumalo and Heany air stations would train twin-engined pilots. There were relief landing grounds at Sebastopol by April 1943, Hienzani from September 1943 and Inkomo from September 1945. Training aircraft used at Cranborne were North American Harvard Mark I, II, IIa & III and Airspeed Oxfords.

North American Harvards [16]

Above: Harvard Mark IIa [17]

The North American Harvard trainer was built in greater numbers than most combat aircraft during WW2, 17,096 being produced. By the end of the war over 5000 had been supplied to British and Commonwealth Air Forces. As conflict became inevitable the Royal Air Force expansion programme demanded a massive increase in pilot training and to meet this need the Empire Air Training Scheme was established. The Royal Air Force soon turned to the United States to acquire the trainer aircraft needed to equip the scheme. The Harvard was one of the first American aircraft ordered by the RAF when a contract for 200 was placed in June 1938. British purchasing contracts reached 1100 before American Lend Lease arrangements began. Some of the first aircraft were delivered to the United Kingdom, but soon after the outbreak of war the majority of flying training units were moved to Canada, Southern Rhodesia and the United States. This made room for operational aircraft in Great Britain and provided safer conditions for training.

Technical Details[18]

| Top Speed | Range | Service Ceiling | Armament | ||

| Harvard Mk I | 180 mph | 850 miles | 24,000 ft | none | |

| Harvard Mk II | 205 mph | 750 miles | 23,000 ft | none | |

| Harvard Mk III | 205 mph | 750 miles | 22,000 ft | none | |

| Harvard Mk IV | 180 mph | 800 miles | 22,400 ft | none |

Training within the RATG scheme

Initial reception for pupil pilots was at Cranborne, where the Initial Training Wing (ITW) course lasted 6 weeks. From here they went onto post initial training for 6 weeks, or to the Elementary Flying Training Scheme (EFTS). Each EFTS intake had 320 pupils spread over the various air stations, about 50 from post initial training and another 270 direct from an ITW course and the course lasted 6 weeks. Those failing were posted back to an ITW course for re-examination. The Service Flying Training Schools (SFTS) had an intake of 64 pupils every 6 weeks at each air station. Some went for air gunner training and others for air observer training. The complete pilot’s course initially lasted six months, ground subjects were also taught and each trainee had to fly at least 150 hours to qualify.

Above: 1941: Three Harvard Mk 1’s flying above the Mazowe valley. (source: Rhodesia Air Training Group photo, IWM)

Training to be an RAF pilot

At Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) the pupil pilot initially studied mathematics and the theory of flight, engines and airframes, some navigation and sent and received Morse code with a lamp. In addition to lectures, there was parade drill, physical training, cockpit drill, and an occasional camp inspection parade. At least 50 hours of basic aviation instruction were required on a simple trainer, such as the De Havilland Tiger Moth; more if the instructors felt the pupil pilot was slipping in on turns, or holding off a little too high on landings, or the take-offs were too bumpy. Once most of the mistakes had been ironed out, the pupil pilot was allowed to fly his first solo flight. Then followed more dual instruction, more solo, more dual, instrument and finally night flying. Having sat and passed an examination, the pupil was ready for posting for more advanced training at a Service Flying Training School (SFTS)

A pupil pilot progressed with a group of colleagues to a SFTS where they would fly bigger and more powerful aircraft, such as the North American Harvard IIA’s, learn the elements of bombing and air firing, formation flying and night cross-countries. The pupil pilot would be allocated to an instructor and in a Harvard trainer they would go through a sequence of gentle, medium and steep turns, take-offs and landings, forced landings and instrument flying, but with the added new complications of a variable-pitch propeller, retractable undercarriage, flaps, boost control, radio and a new array of instruments.

Lectures would continue with advanced plotting courses, studying the line of fall of various bombs, using a radio, understanding weather conditions, recognition of allied and enemy aircraft. Advanced instrument flying was practised on a link-trainer, landing by radio when the clouds “were down on the deck” and firing a machine gun whilst allowing for the deflection necessary when shooting at a flying bomber. Hours were spent “under the hood” using instruments to fly from point to point on a map, and long night-time cross-country flights.

The Harvard’s Pratt & Witney 600 hp Wasp radial engine was much more powerful than the De Haviland Gipsey III 120 hp engine in the Tiger Moth. Advanced aerobatics were possible and low flying gave a great thrill. As the pupil pilot advanced there would be formation flights in vic (“V” shape) echelon and line astern, learning to watch his leader and keep one eye roaming around the sky. There would be flights to a relief landing ground from where they would practice flying each morning and then intercepting a twin-engined Airspeed Oxford that would have been tasked with bombing a target in the same area.

Finally, the great day arrived when the pupil pilot received his wings. This left just time for a final party in town to celebrate the event before he was sent north to an operational unit in North Africa or the UK. Here he would be introduced to the Spitfire whose details would be carefully explained with much cockpit drill before he was allowed his first solo with no second cockpit to carry a watchful and helpful instructor.

Burial [19]

1348081 Sergeant U/T Pilot William Arthur Dent, buried at grave 108, Harare [Pioneer] Cemetery, Zimbabwe. Sergeant I.T. Thomson and is buried next to him. There are 224 Commonwealth burials of WW2.

The following words are inscribed on his headstone:

Blessed

Are the pure in heart

For they shall see God

Above: Headstone of 1522988 Sergeant W.A. DENT Pilot U/T RAF

Above: 1348081 Sergeant I.T. THOMSON (Pilot) RAF

Above: Harare [Pioneer] Cemetery, Zimbabwe

Above: Evenwood Cemetery: Headstone of Elizabeth Annie Fryer

and commemoration to her son Sergt. William Arthur Dent

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to:

- For family details – Aline Waites and Carena Parmley

- For military details and headstone photographs – David and Joan Evans (good friends and supporters of ER&DHS) and Dave’s friends in Zimbabwe viz. Peter Locke, John Reid-Rowland, Kevin Atkinson, Martin Hartell and especially Rob Anderson for the headstone photos.

REFERENCES

[1] Commonwealth War Graves Commission Note: U/T means under training

[2] Birth certificate registered 5 February 1923

[3] England & Wales Marriage Index 1916-2005 Vol.10a p.374 1921 Q2 Auckland

[4] 1911 census

[5] Army Form 2513 Statement of the Services for 7734 Guardsman Arthur Dent, Guards MG Regiment

[6] 1939 England & Wales Register

[7] 1921 census

[8] The commemoration to those who took part in the Boer War in Bishop Auckland Town Hall names a W. Thompson who served with the Imperial Yeomanry. 27118 Corporal William Robert Ramshaw Thompson served with the Imperial Yeomanry but he is not the same man – an Ancestry family tree identifies him.

[9] 1939 England & Wales Register Note: 2 others lived there at the time of the “census” but their “record is officially closed” which infers at the time of disclosure of the register, they were still alive and their privacy was respected.

[10] England & Wales Marriage Index 1916-2005 Vol.10a p.539 1944 Q3 Durham Western

[11] 1911 census

[12] 1939 England & Wales Register

[13] Other places are referred to by their names in 1940 are Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), Bechuanaland (now Botswana), Gwelo (now Gweru), Selukwe (now Shurugwe) and Umtali (now Mutare).

[14] It is believed that Grove Farm was owned by the Staunton family possibly now VP Chiwenga.

[15] https://zimfieldguide.com/harare/rhodesia-air-training-group-ratg-1940-%E2%80%93-1945

[16] https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/research/collections/north-american-harvard-iib/

[17] https://www.italeri.com/en/product/2385

[18] https://www.classicwarbirds.co.uk/american-aircraft/north-american-harvard.php

[19] CWGC