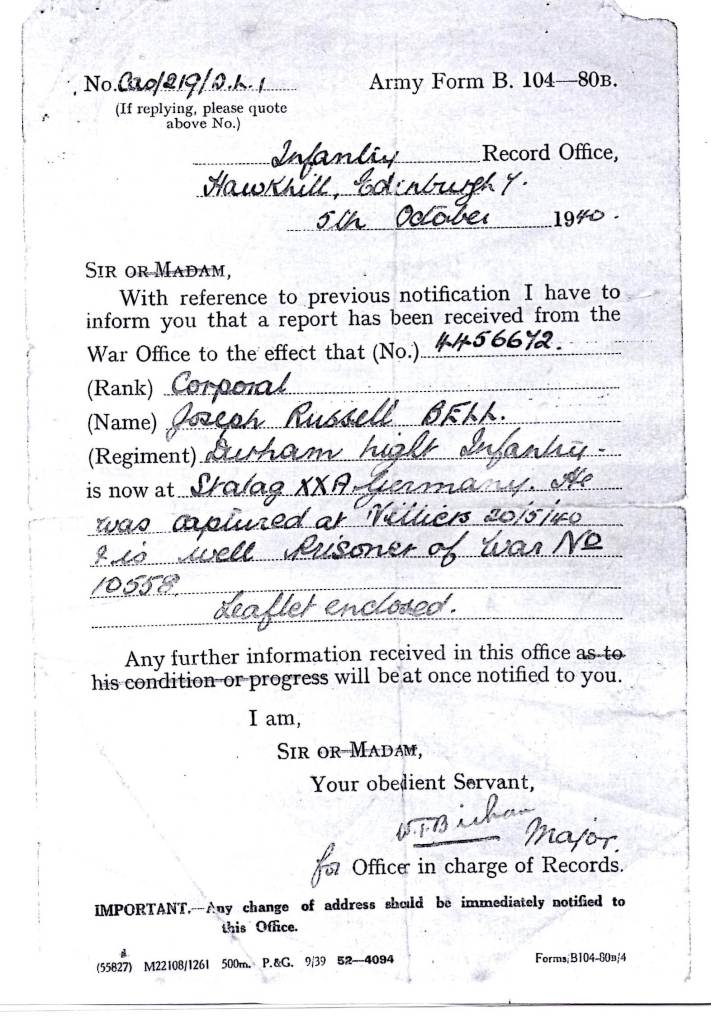

Corporal Bell was captured 20 May 1940 at Villiers and arrived at Stalag XXA 10 June 1940. It is not known how he got to there. [1]

Evacuation and POWs [2]

It is recognised that the actions around Arras, in which the 10/DLI were involved contributed towards delaying the German advance which in turn allowed more valuable time for the evacuation of British and French troops from Dunkirk. The evacuation was by no means the final act of the Battle of France. Other troops were stranded and continued to engage the enemy such as the 8,000 soldiers of the 52nd Lowland Division & 1st Canadian Division fighting at Cherbourg and the 51st Highland Division still resisting at St. Valery, near Le Havre. The French capitulated 17 June 1940. Remaining behind were about 40,000 British and 100,000 French POWs who were to start a new chapter of their lives under the Nazi regime.

Surrender

Generally, many soldiers surrendered in twos and threes, arms raised and were taken to holding pens, hastily erected barbed wire enclosures in open fields. The battered and bloodied survivors of the defeat and the rear-guard action were slowly herded together and were then marched to larger pens with hundreds of others. These men joined up with other crowds until thousands were bundled together into vast khaki-clad hordes. The men were searched and personal possessions taken. There was some brutality and some humiliation. Most disconcerting of all, there were massacres:

- Le Paradis 27 May 1940: about 90 soldiers from 2/Royal Norfolk Regiment were taken by 1st battalion, 2nd Infantry Regiment, of the SS Totenkopf Division and executed.

- Wormhouldt 28 May 1940: about 50 or more 2/Royal Warwickshire Regiment were killed by the SS.

But generally, it seems that the front line infantrymen of the Wehrmacht treated the men with sympathy, although any escapees were shot. The prevailing feeling of the POWs was of despair and degradation. They formed endless columns of marchers heading eastwards towards Germany. The route was either:

- To Rhineland, to the city of Trier then they were entrained to Stalags across “the Reich”

- To Bastogne, then onto trains to Germany and beyond.

- A northerly route to River Scheldt then onto barges. The captured men of the 51st Highland Division took this route.

- Up to Belgium to Maastricht into the Netherlands then barge to the Rhine to Dortmund, Germany.

- To Cambrai, France then onto trains. It is likely that Corporal Russell Bell and other 10/DLI soldiers took this route since Cambrai is the nearest of these towns to the Arras area where they were captured.

Usually cattle wagons or coal barges were the favoured means of transport. Uppermost in the minds of the POWs was food and drink, upholding military discipline and the attitude of their guards. The Geneva Convention insisted that the Officers had to be separated from the Other Ranks thus the NCOs were responsible for discipline. They were often jeered by lorries of infantry men going to the front. The daily marches varied in length. The Geneva Convention suggested that they should not exceed 12 miles (20km) but often much greater distances were covered. The overnight stops were generally in the open air with little protection against the elements. Kit had been discarded. There was much thieving amongst the POWs. A contemporary account explains the situation:

“It was survival of the fittest…Self-preservation was the predominant thought…There wasn’t too much anger against the Germans – only when they kicked buckets of water over……Let’s face it, we weren’t trained soldiers, we were just there because we had to be. So we thought it was just hard luck.”

The marches were summed up as follows:

“The toil of the long marches – the aching muscles from days of walking, the pain caused by sleeping on cold damp ground, the empty bellies and shrinking waistlines, the blistered feet, the calluses, and carbuncles caused by equipment that rubbed – all created a deep sense of despair for the prisoners. Unwashed, clad in stinking, sweat-stained blouses that rubbed at their necks and heavy woollen trousers that scraped their crotches, leaving their skin red-raw, they marched on.”

However, not all those left behind were POWs. It was reported that by February 1941 there were still about 1000 British soldiers regarded as “evaders” in hiding throughout France and Belgium, some working on farms. By September 1941, the figure was revised to 5,000 men. Some tried to get home via Switzerland.

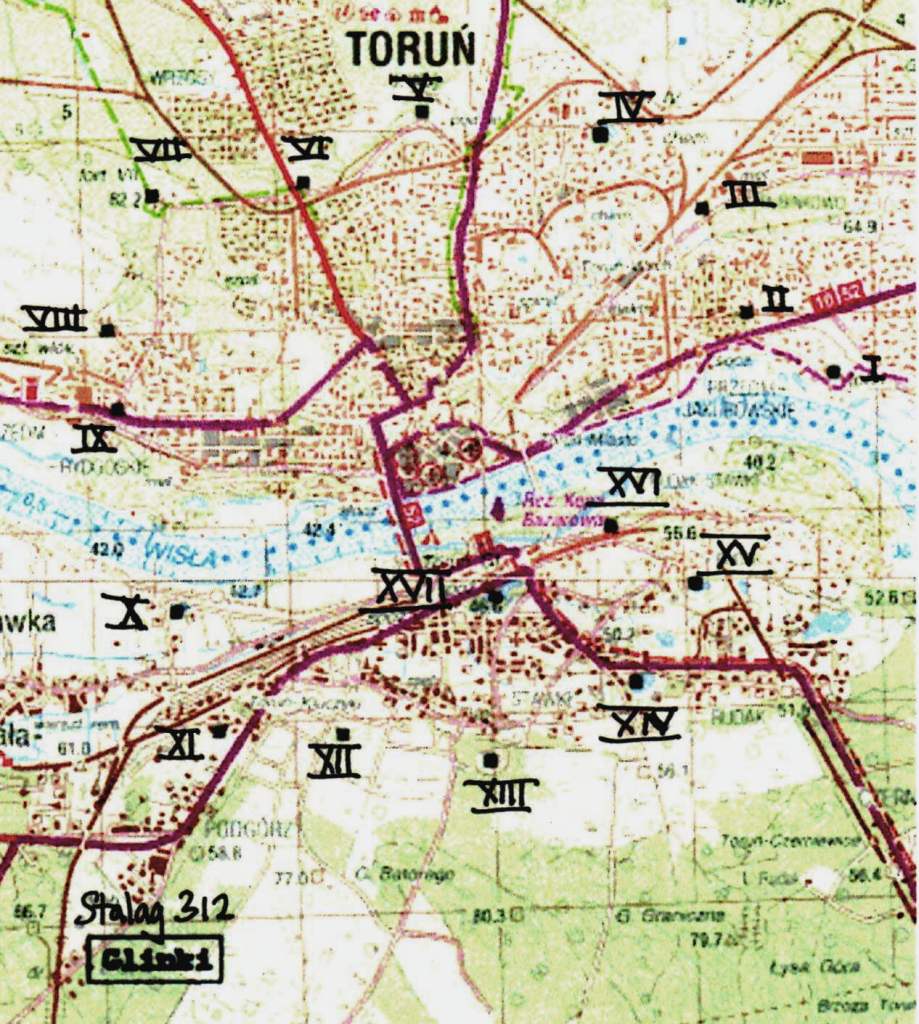

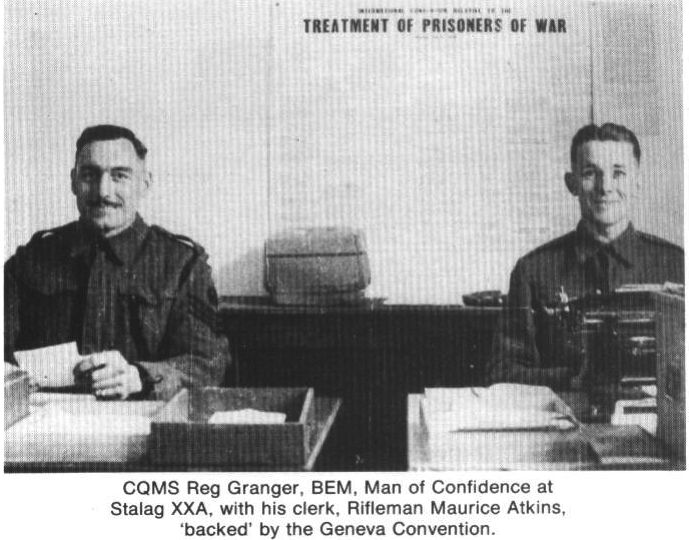

POW Camp: Stalag XXA located at Thorn

Stalag XXA was located at Thorn (now called Torun). It was not a single camp but a complex of 17 Prussian forts that surrounded the city. By September 1939, Polish soldiers and civilians were held captive here. The camp held as many as 20,000 men at its peak. Throughout the war, Stalag XXA held some 55,000 POWs of which 21,000 were Russians, 12,000 were British, 5,000 French, 15,000 Italians, with Belgians, Poles, Americans, Serbs and a number of Norwegian doctors. In June 1940, the first POWs to arrive were 403 servicemen from the Allied campaign in Norway and they were joined by about 4,500 from Dunkirk. Soldiers of the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division were held at Fort XI.

Incoming POWs arrived either at the railway platform or the siding beside the main station. They were then taken to Fort XVII which served as a transit camp where they were recorded and distributed to appropriate accommodation within the camp or taken elsewhere. Many POWs were sent to work camps. There were 190 such work camps located at places such as Annowo, Boguszewo, Allahbad, Brusy, Bydgoszcz, Cierpice, Chelmo, Chojnice, Grudziadz, Gutowo, Jarantowice, Kikol, Naklo, Novogorod, Przylubie, Krajenskie, Radzyn, Chelminski, Solec, Kujawski, Siemkowo, Tuchola, Tuszkowo, Crow, and Wytrebowice. POWs had to work on farms but some worked in factories, brickworks or whatever was deemed essential to the Nazis. It is understood that Cpl. Bell worked at Tuchola, in a brick-works and it was there where he met Jan Glowacki [more of this later].

Between October 1940 and December 1941, there were 44 deaths. The dead were buried in the garrison cemetery at Torun. The funerals observed military custom – the coffins were draped with the national flag, a 6-gun salute with 20 colleagues in attendance.

Living conditions for the western European and US POWs was mainly in accordance with the principles of the Geneva Convention. Lack of food was always a problem but POWs were allowed to barter with Poles working at the camp. Intellectual entertainment was permitted. There was a library, a camp newspaper, a band and a theatre. Sports were allowed. Punishment for offences against the regulations such as attempts to escape, arrogant attitude, theft, bad work, disobedience resulted in prison sentences of 7, 14 or 21 days. In accordance with the Convention, sentences could not exceed 30 days.

Contemporary descriptions of Stalag XXA

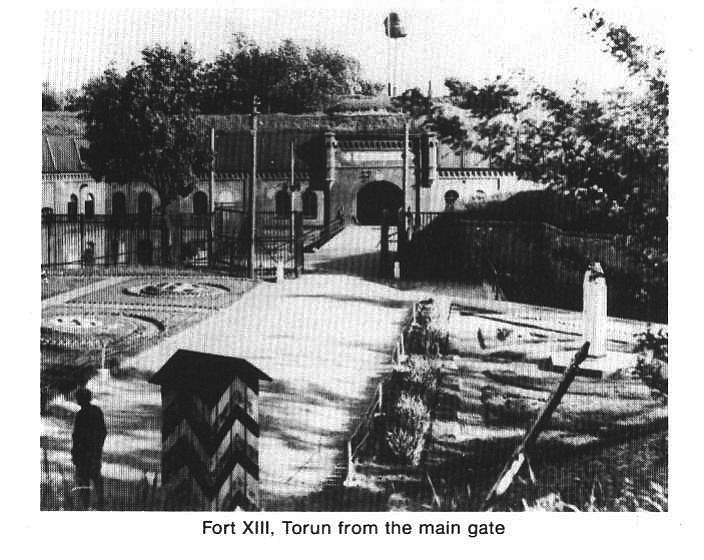

“At Thorn the train arrived directly outside the gates of a vast complex of forts that had been constructed in the nineteenth century following the Franco-Prussian War.

Fred Coster recalled when the cattle wagon doors finally opened to allow them out:

“They shouted Raus! Raus! As we jumped out we all just flopped to the ground. Then we dragged ourselves up to walk into the camp. For me, as I was walking along, it didn’t feel like it was me walking – it was as if my spirit was pulling me along.”

A loudspeaker announced that, “They had refused to fight for Churchill” which was a crude attempt at propaganda designed to humiliate them. It is unlikely these men, suffering from exhaustion and malnutrition would be bothered by such tactics. Another contemporary account describes Thorn as follows:

“My view was dominated by 2 massive gates made of wood, laced with barbed wire. These gates I then noticed were the entrance to a vast flat piece of ground which was surrounded by a double fence of barbed wire. I noticed that each corner of this compound held a raised machine gun post manned by German guards. The 2 gates were also manned by 2 guards, one of whom opened the gates on our arrival. We were told to enter whilst the other guard counted us in. It was all so bewildering, especially as I was aware of a commotion inside the compound where there were already many, many POWs settled in.”

There were 3 categories of prisoner

- Officers who lived in separate quarters to the men they had led in battle. They lived in segregated camps or in enclosures away from the men. The officers did not live in better conditions.

- the NCOs above the rank of corporal who were excused from work by the conditions of the Geneva Convention

- the vast majority of POWs were employed at the work camps. There were advantages in going out to work – trade with the local workforce, parole! Walks in the countryside! But men were pitted one against another, the atmosphere was terrible, there were arguments, some stole from each other. Those who gave the Nazi salute were beaten by their fellow POWs. Sometimes gangs formed and took over life in compounds – cosh boys and razor gangs from the pre-war city slums. Usually discipline was controlled by senior NCOs. There were some “rotten NCOs” who looked after themselves and their ilk but generally the senior men looked after and organised the POWs. At Thorn, apparently a Scottish sergeant-major was responsible for making many of the POWs into soldiers again.

Above: A party of POWs, Russell Bell is second row, 5 from the left.

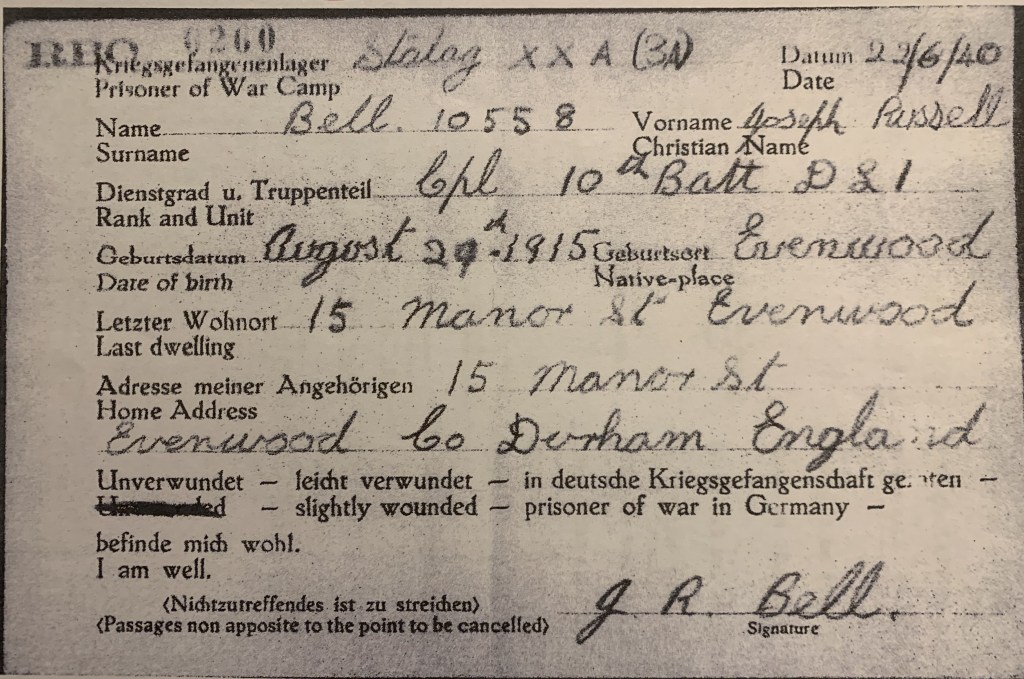

Above: Corporal Russell Bell’s POW Registration Card

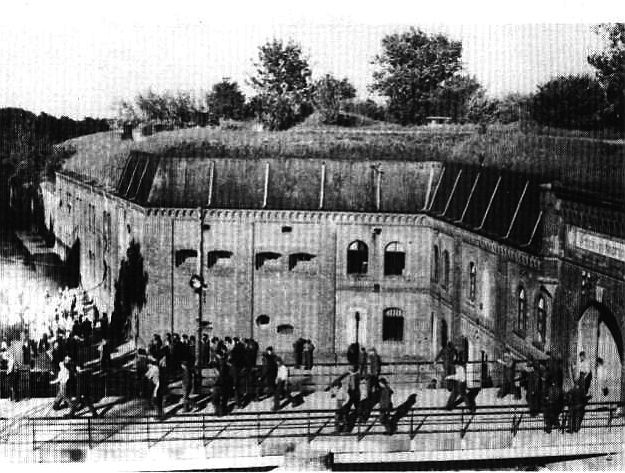

The prisoners arriving at Thorn were sent into tented camps for registration but first their heads needed to be shaved then delousing took place in a steaming shower room. The de-louser didn’t kill the lice! They were photographed holding their POW number, issued with a rectangular tag or disc stamped with their identification number which they would wear every day for the next 5 years. They were then searched. All spare clothing was taken away. They filled in Red Cross Forms which were used to notify British authorities that they were POWs. Then they were washed down with high pressure hoses. The spray knocked them down. A small rough towel and some soap were made available for use and new uniforms (which smelt like a damp bog) and wooden clogs were issued. They slept on the straw covered floor in a subterranean storeroom. The POWs were then sent to Fort 17 which was a series of wooden huts, sheds which housed about 1000 prisoners. They spent hours cracking lice! The latrines stunk.

Graham King describes the accommodation:

“the rooms contained beds, the same design as those seen in pictures of concentration camps. Three shelves were against the wall, about 6 ½ ft. wide with a gap of 1 m between the bottom shelf and the middle and between the middle and the top. The best position was the top because there was more light there and there was no-one tossing and turning above you, vomiting or suffering loss of bladder control. In each room there were about 30 men living.” The rooms “were like semi tunnels; all the ceilings were arched to give strength. The perpendicular walls were about 3m high and the height to the arched roof was about 5m. The width of the room was about 5m and the length about 15. Three tiered wooden bunks provided sleeping spaces and 32 men would sleep, eat, argue, smoke, fart, cough, snore, groan, moan, play cards, have nightmares and read in each of those rooms…each had 2 small windows over which blackout blinds had to be fitted every night. Theses allowed no ventilation. By the end of the night the air was solid and everyone would have a headache due to oxygen starvation.”

The forts were mainly underground with prisoners living in 2 storeys, in 50 dark rooms, each holding around 30 men that ran along the rear. At the front of the fort were open courtyards below ground level. A POW, Graham King later discovered that the moat contained a surprise:

“It was a dry moat, rather overgrown but surprisingly teeming with rabbits. In our early days in this fort we had tried to trap some using snares but were told by the Germans that snares were banned in Germany and the punishment was quite severe.”

Most men lost weight quickly. There was a shortage of food. Life revolved around food and water. The first task was to find something to hold food – no container, no food! Graham King recorded his daily rations in the early weeks:

“The day began at 6am with coffee made from roasted acorns. For lunch they received a litre of vegetable soup with no meat or fat. At 4pm they received 1,500 gram loaf of black bread, one between 5 men. With this they received a little margarine, honey, jam or very occasionally liver sausage. He recalled that after the deprivation of the journey from France, so much food seemed like a feast. That said it was still not enough to help them recover.”

The rations were supplemented by the Red Cross parcels. When these arrived at Thorn is unknown but elsewhere, some arrived in August 1940. Others had to wait until March 1941 – a cardboard box no bigger than a shoebox, brought joy to the lives of the POWs. Gold Flake cigarettes were currency – a loaf of bread could be bartered for! Tins of condensed milk and a tin of kippers had to be shared out. The reality was that there were too many prisoners and not enough food:

“The vast numbers of prisoners absorbed into the stalag system meant that resources were stretched beyond even Hitler’s expectations.”

Sickness was rife within all POW camps and some of the weakest men gave up and died, hundreds found themselves so weak they could barely move. Life continued to revolve around dreaming of food and then rushing to the stinking latrines as the men were gripped by stomach cramps and diarrhoea. The situation was succinctly summed up as follows:

“I don’t think anyone did a solid crap the whole time they were prisoners.”

Other illnesses such as TB struck the men. At Stalags XXA and XXB there were deaths among the TB patients, resulting in some being transferred to Stalag IIIA. Some went mad. One POW jumped off a roof. They suffered from skin sores, loss of teeth, hair loss, stomach cramps and diarrhoea.

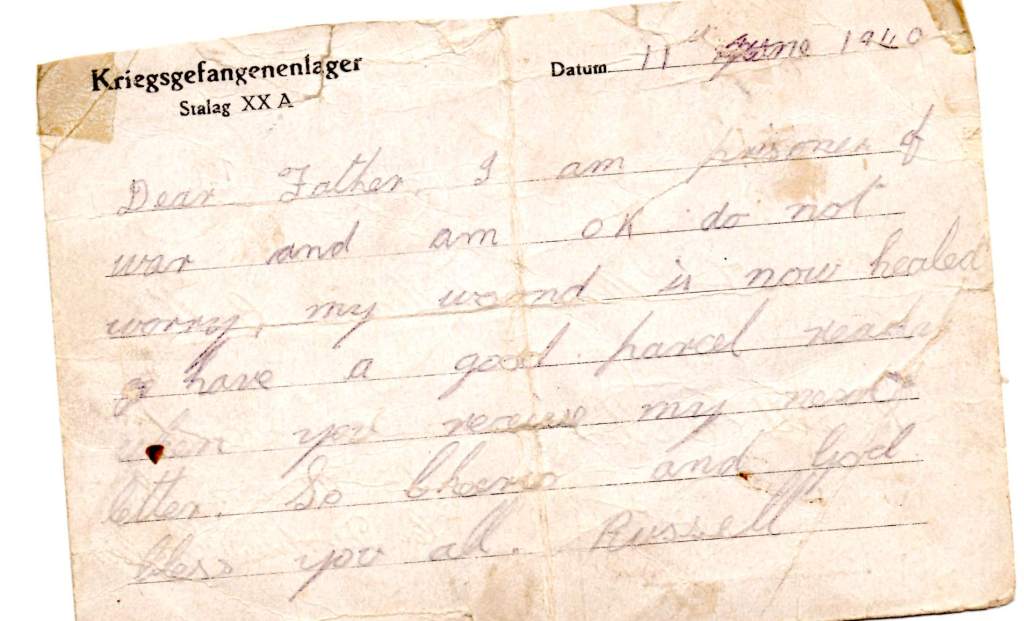

POWs were allowed letters home – 4 postcards and 2 specially designed lettercards each month. No news of conditions within the camps or military details was allowed.

There are 6 letters from Corporal Bell:

11.06.1940 Stalag XXA

“Dear Father – I am a prisoner of war and am OK, do not worry, my wound is now healed, have a good parcel ready when you receive my next letter. So cheers and God bless you all. Russell”

25.06.1940 Stalag XXA Camp 3A

“Dear Father and family, I am keeping OK send me parcels regular with food such as meat pastes and spice cakes also OXOs and a bar of soap sometimes. Tell Ena and write to Connie address is 41A Bondgate. Let me have all the news and where is Fred, send you a photo. Russell”

Ena was Ena Birney (nee Bell), a cousin from Ireland who named her youngest son after Russell, Connie was his girlfriend and Fred Monk was the future husband of his sister, Doreen.

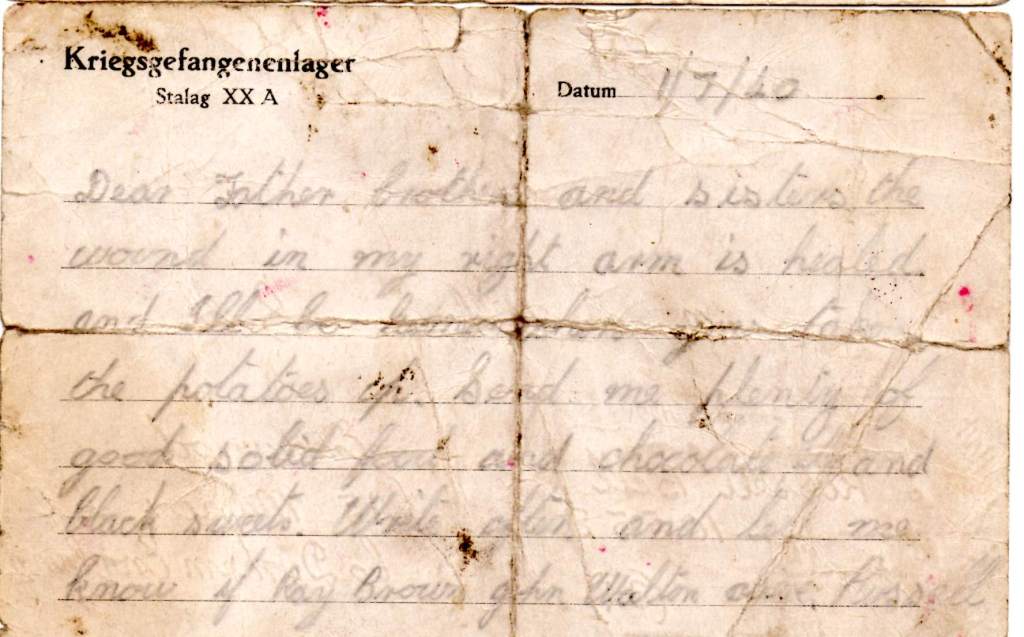

01.07.1940 Stalag XXA Camp 3A

“Dear Father, brother and sisters. The wound in my right arm is now healed and I’ll be home when you take the potatoes up. Send me plenty of good solid food and chocolate and black sweets. Write often and let me know if Ray Brown, John Walton alive. Russell”

Ray Brown was killed and John Walton was a POW and worked in coal mines in Poland. He survived the war.

03.11.1940 Stalag XXA Camp 3A

“Dear Father and Family, I hope you are all OK the same as me and I wish you many happy returns of your birthday Nov.5. You may use that money of mine for anything you like and I hope you have a happy Christmas. So cheerio, Russell”

- Stalag XXA Camp 17

“Dear Father, hope you are all OK at home the same as I am. I would like you to send me a pair of boots because mine are done and also send me some chocolate. Well the weather here is much warmer now and I can picture what it is like in England. So cheerio, Russell”

28.02.1943 Stalag XXA Camp 5

“Dear Doreen, I hope you have heard from Madge about the ring, give her all the money she wants for a good one. They are very dear these days. Oh I had a lovely letter from Aunt Sadie. She asks about you all, you have got to write. I received a 100 cigs. Do you know who sent them. Russell”

Aunt Sadie was Russell’s father’s sister who lived in America. Madge was possibly Marjorie Peart.

There is also an undated note which states, “Also tell Mrs. Brown that I’m sure Ray will turn up.”

Corporal Bell was captured at Villiers, France 20 May 1940 on the same day that 19 years old Private Ray Brown, 10/DLI from Copeland Row, Evenwood was killed in action. He is buried at Bucquoy Road Cemetery, Ficheux, France.

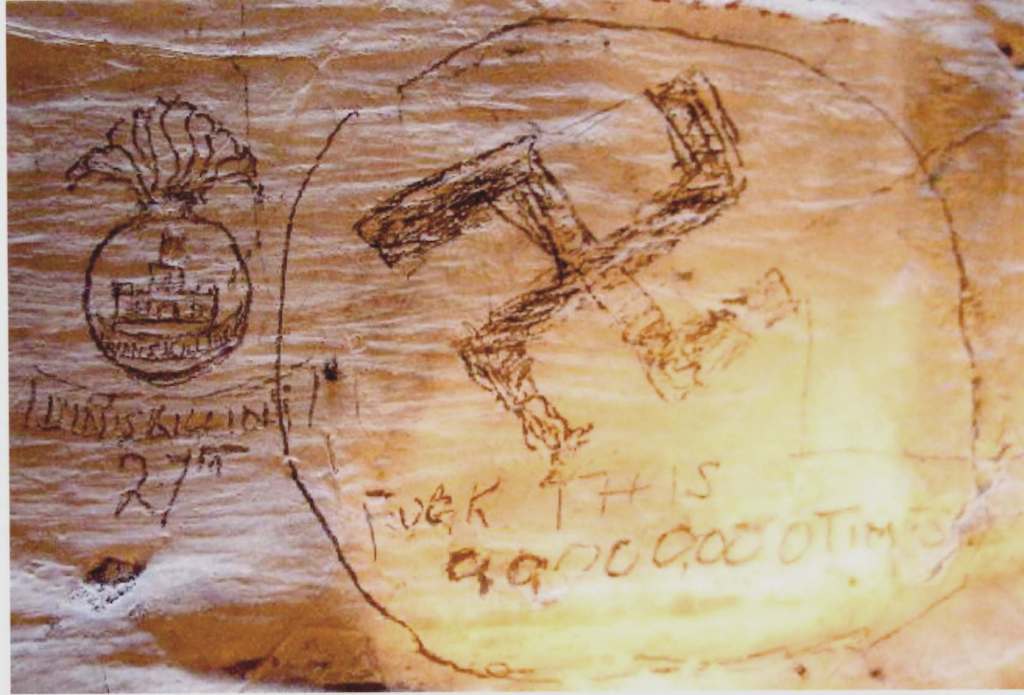

Above: Examples of graffiti written by British POWs.

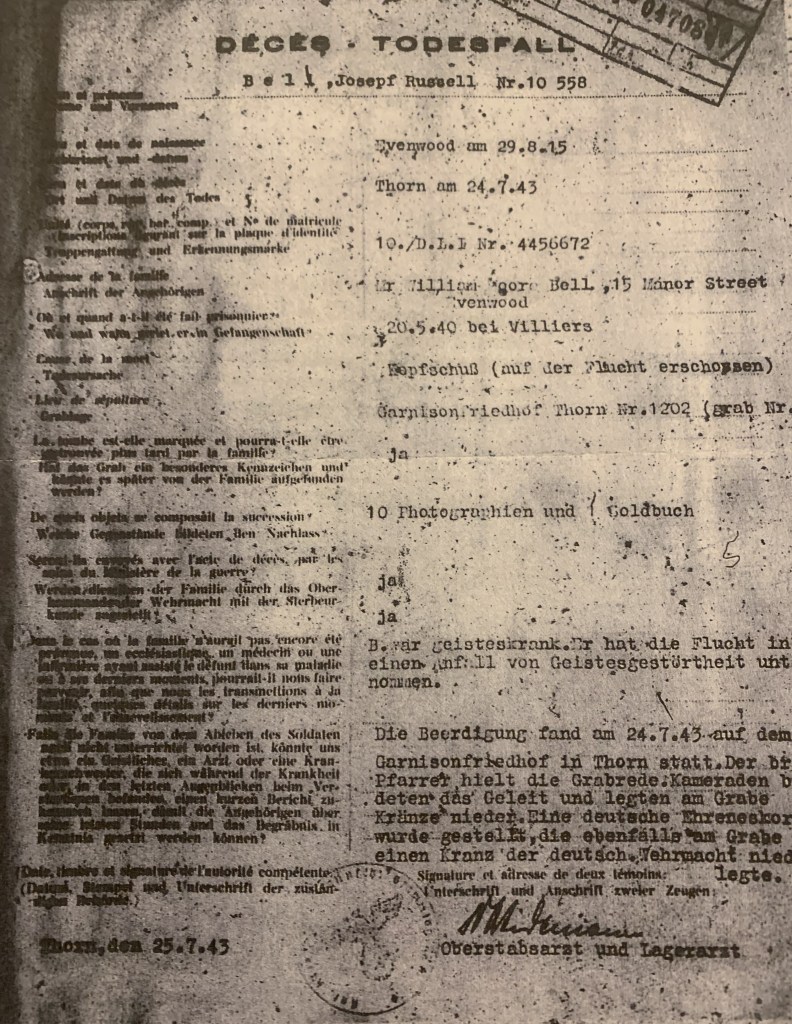

Corporal Russell Bell was shot whilst attempting to escape 24 July 1943.[3]

Above: The Report relating to his death: translation below:

“Kopfschuss auf der Flucht erschossen” translation – shot in the head while trying to escape.

“B. war geisteskrank Br. hat die Flucht in einen Anfall von Geistesgesturheit unternonwen.” – B. was mentally ill. Br. fled in a fit of mental stubbornness.

“Die Beerdigung fand am 24.7.43 auf dem Garnisonfriedhof in Thorn statt. Der brit Pfarrer hielt die Grabrede Kameraden bildeten das Geleit und legten am Grabe Kranze gestellt die ebenfalls am Grabe einen Kranz der deutsch wehrmacht niederlegte” – The funeral took place on July 24, 1943 in the garrison cemetery in Thorn. The British priest gave the eulogy. Comrades formed the escort and laid wreaths at the grave, and the German Wehrmacht also laid a wreath at the grave.

Above: A funeral at Stalag XXA, Thorn.

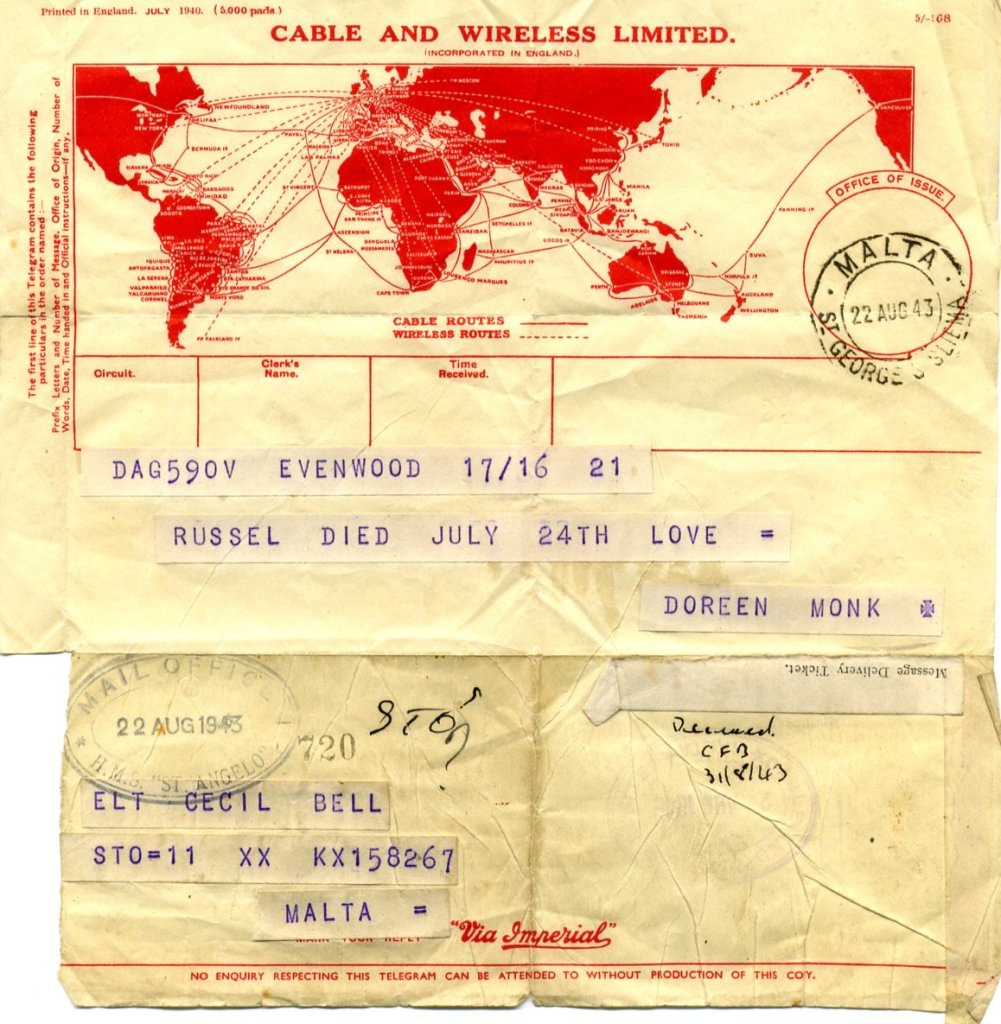

Above: Telegram from Russell’s sister Doreen to his brother Cecil, who served in the Royal Navy stationed in Malta.

Above: A Memorial to the memory of the POWs at Stalag XXA, Thorn.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Bell family and in Poland – Pawel Bukowski, Grzegorz Borkowski & Hanna Gadziomska.

Muzeum Historyczno-Wojskowe, Fort IV, Torun, Poland

REFERENCES

[1] International Committee of the Red Cross letter dated 21 October 2011

[2] “Dunkirk – The man they left behind.” Sean Longden 2008.

[3] International Committee of the Red Cross letter date 21 October 2011