The purpose of this work is to provide information on proposals to develop a canal network in south Durham in the 1760s and 1770s, suggested by the eminent engineer James Brindley and the Dixons of Cockfield. It will identify the proposed routes and the collieries which they were intended to serve. These schemes failed to attract financial support and the opportunity was then available for an alternative transport system. Railways met the challenge. South Durham and the coalfield to the north was at the heart of the “railway revolution” which was to take place the following century.

TURNPIKES

From the mid-1700s, the following turnpike roads were operational in south west Durham:

- 1747 Stockton to Barnard Castle

- 1748 Sunderland Bridge to Bowes

- 1751 Darlington to West Auckland and Red House (High Etherley), known as, “The Coal Road.”

- 1761 Staindrop to Gately Moor (Gilling West)

Sections of these roads were used to transport coal and other goods by pack horse and carts from the local collieries around Bishop Auckland to markets at Darlington, Barnard Castle, Richmond and beyond. Some pits were located off the beaten track. For instance, the Butterknowle Pits were located west of Evenwood Park and north west of Lands Farm and Lynburne and Rowntree pits were further to the north west.[1] Turnpike roads did not reach these areas. These pits were served by ancient cart tracks.

Local coal owners and coal merchants wanted their mines connected to Stockton-on-Tees. By reaching a port their coal would be less expensive due to reduced transport costs and more competitive. New markets for their coal would be opened up and their enterprises would thrive and expand. In October 1767, local industrialists recognised the need for better communications between the largely undeveloped coalfield of south west Durham and Stockton-on-Tees. This period was the heyday of canals and this may have seemed to be the obvious solution.

1768: STOCKTON TO DARLINGTON TO WINSTON CANAL

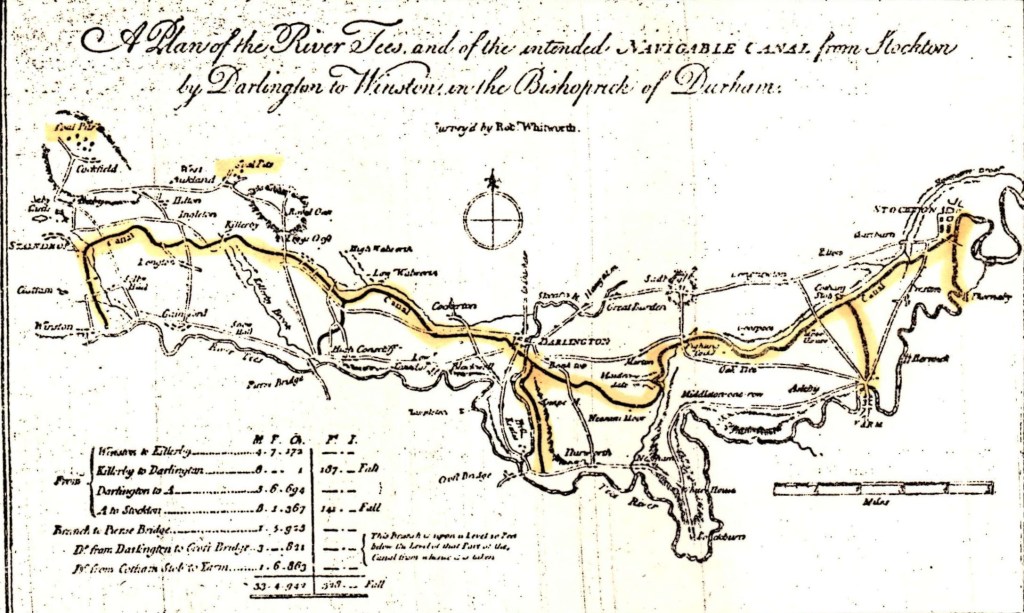

The River Tees was tidal and navigable from Seal Sands up to Stockton and Yarm. In 1768, James Brindley, the eminent engineer of the day, was engaged to design a canal from Stockton to Darlington to Winston, Robert Whitworth surveyed the route.

Above:

1768: A Plan to show the proposed route of the Winston to Darlington to Stockton Canal.

A detail of the 1768 Stockton to Darlington to Winston map shows the western route of the proposed canal. It was proposed to run from Winston north to Staindrop, then north of Langton and onto Killerby, north of Summerhouse and onto Denton to Low Walworth, Archdeacon Newton, Cockerton and Darlington. [2]

Above: A Detail of the Title Block

Above: A Detail to show the Western Section of the Proposed Canal with extensions to Piercebridge and Croft.

Five coal mining areas shown on the map:

- North of St. Helen’s Auckland probably owned by the Musgrave family.

- North of West Auckland at Greenfields, probably owned by the Eden family.

- North of Toft Hill and Etherley – the Railey Fell, Etherley and Witton Park Collieries, probably owned by Richard Pierse.

- North of Evenwood – the Norwood Colliery on land owned by Lord Strathmore and worked by Dixon and Flintoff.

- North of Cockfield probably Copley Lane, probably owned by the Earl of Darlington.

Above: A Detail to show the Coal Mines West of Bishop Auckland

Above: A small coal pit worked by two men with a windlass.[3]

The Dixons were a notable local family. George Dixon (about 1553-1631) of Ramshaw Hall was in the employment of the Bishop of Durham and collected taxes in the Barony of Evenwood. George Dixon (1635-1707) was a Quaker and an early follower of George Fox. George Dixon (1671-1752) held a senior position for Gilbert Vane, 2nd Baron Barnard at Raby Castle. Sir George Fenwick Dixon (1701-1755) was a coal mining magnate in Bishop Auckland and Cockfield. His son George Robertus Dixon (1713-1785) continued the family tradition of coal mining interests. His younger brother Jeremiah (1733-1779) was the celebrated surveyor and astrologer. During the late 1760s into the 1770s, it is understood that the Dixons worked collieries at:

- Norwood Colliery on land owned by the 9th Earl of Strathmore (John Bowes 1737-1776).

- Cockfield Fell on land owned by the 2nd Earl of Darlington (Henry Vane 1726-1792).

Above: John Bowes (1737-1776) 9th Earl of Strathmore

Above: Henry Vane (1726-1792) 2nd Earl of Darlington[4]

Believed to be George Dixon (1713-1785)

It is understood that Jeremiah Dixon was responsible for surveying the routes of two proposed canals from the collieries in the Gaunless Valley at Cockfield, Norwood, Butterknowle and Lunton Hill and another from Witton Park, Railey Fell, West Auckland and Norwood Colliery to join the proposed Winston to Darlington to Stockton canal.

Above: Believed to be Jeremiah Dixon (1733-1779)

Above: An illustration of Charles Mason & Jeremiah Dixon surveying the boundary between Pennsylvania and Maryland (The Mason-Dixon Line) 1763-1768

1769-70: THE PROPOSED BRANCH CANAL FROM THE MAIN CANAL NEAR KILLERBY TO THE COLLIERIES [5]

The plan shows two canals and associated waggon ways which connected the collieries of the western part of the Auckland Coalfield to the proposed Stockton to Darlington to Winston canal. These two canals were:

- An eastern route from Railey Fell, Witton Park, West Auckland and Norwood collieries which followed the 150m (about 500 feet) contour for most of its approx. 20km route. (about 12½ miles). The route travelled eastwards from Sloshes Lane to Etherley Grange and swung south westwards to Deborah Wood then westwards along the north side of the River Gaunless, south of Ramshaw Hall, around Gordon Gill towards Lands Farm. Turning eastwards along the south side of the Gaunless Valley, locks would be needed to gain height from west of Lands Farm to the higher land to avoid Cragg Wood. Alternatively, it may have been decided to fell a way through Cragg Wood to reduce the climb and reduce the number of locks. The plan is not clear at this point. Continuing eastwards, over Oaks Bank and around Copeland House, the route meandered through the gently rolling countryside, southwards towards New Moors, Bolton Garths and east of Hilton. The canal terminated between Quarry House and Morton Tinmouth. From there a waggon way was proposed, approx. 1.5km (about 1 mile) down the hillside, a fall of approx. 60m (about 200 feet) south eastwards towards Kiln Lane, near New House Farm at Killerby. From there, the waggon way joined the proposed Winston to Darlington canal.

- A western route from Norwood, Butterknowle, Cockfield Fell, Copley and Lunton Hill collieries followed the 190m (about 625 feet) contour for most of its approx. 12km route (about 7½ miles). The route set off westwards along the north side of the River Gaunless, passing by Haggerleases Lane, sweeping around Salterburn and Grewburn then heading south over Copley Bent and the River Gaunless, south to Peathrow and Wigglesworth. Locks would have been required to climb over Cockfield Fell where there is an increase in height of about 35m (115 feet). A gentle meander around Cockfield and descent south eastwards followed to land west of Esperley Lane before meeting the 190m contour again, east of Keverstone Grange where this canal terminated. From there a waggon way, approx. 2.5 km, (about 1½ miles) travelled southwards down the hillside, a fall of approx. 90 m (about 300 feet) to an area east of Carr House, 1.4 km (0.9 mile) east of Staindrop. From there, the waggon way joined the Winston to Darlington canal.

Above: The Dixon Plan superimposed on a modern OS map (Note: Lunton Hill Colliery was further to the west)

The Eastern Waggon Way

Above: View from the Ingleton to Killerby road looking northwards up to the Bolam ridgeline. The proposed waggon way would have run between the white buildings down the hillside and across the fields.

Above: View from the Hilton to Morton Tinmouth road looking south eastwards over the Tees Valley. The proposed waggon way would have run down and across the field between the trees.

The Western Waggon Way

Above: 2025: The view northwards from Alwent Hall looking up to the Keverstone ridgeline. The proposed waggon way would have run down the hill side to the east of Low Keverstone Farm, to the right of the white farm building to the mid-left of the photo.

Above: 2025: The view southwards over Low Keverstone Farm down to Carr House, east of Staindrop. The proposed waggon way would have run down the hillside to the left of the farm.

It is believed that a stretch of canal was dug out on Cockfield Fell but the 2nd Earl of Darlington was not impressed with the venture. The 2nd Earl was an agriculturalist and planted many of the woods around Raby.[6] This background may have influenced his decision.

Above: c.2024: Cockfield Fell, believed to be the site of Dixon’s trial canal.

A report was published by Brindley and Whitworth, 19th July 1769 [7] and estimated the cost at £63,722 which was:

“more than could be raised from a public which was not accustomed to large investments and the scheme was taken no further.” [8]

The prime subscribers included: [9]

- The Earl of Darlington, The Hon. Fred. Vane of Raby Castle

- Sir John Eden, Windlestone

- Sir Ralph Milbanke, Halnaby

- Sir Laurence Dundas, Aske

- Sir Edward Blackett, Maften

- Thomas Dundas Esk., Marske

- Charles Turner Esk., Kirkleatham

- Jenisson Shaftoe Esq.,

- George Hartley Esq., Richmond

The scheme did not progress. Regardless of this setback, coal mining continued in this isolated part of south west Durham.

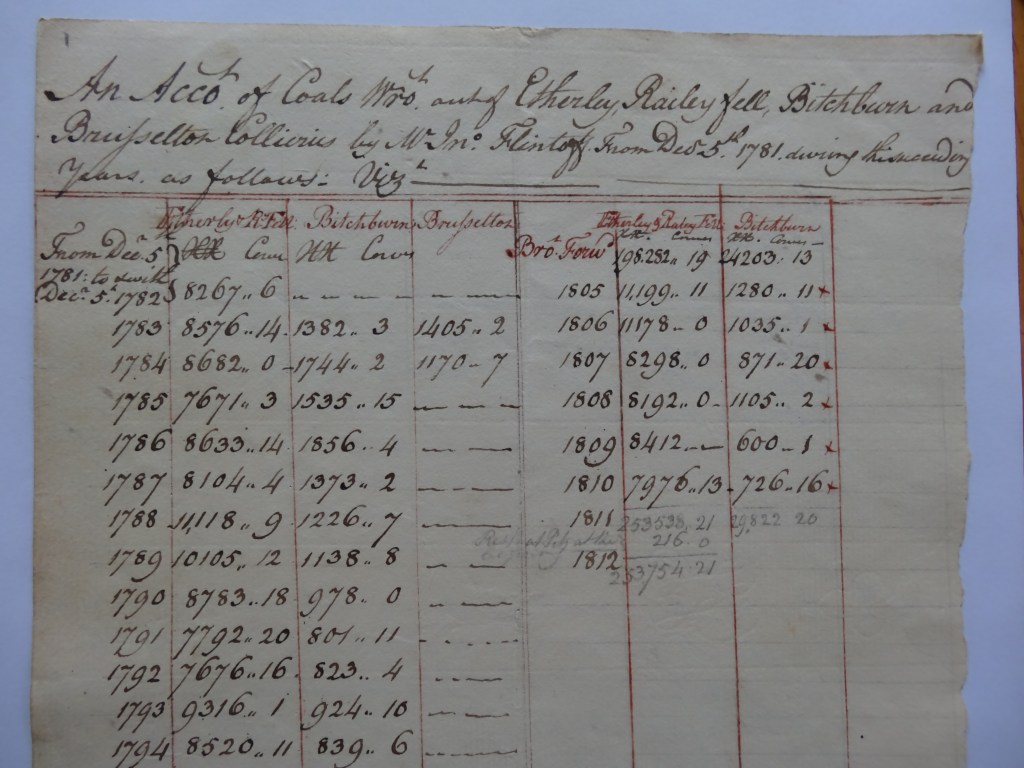

1781-1811: There are a series of legal agreements made over a 30-year period between 1781 and 1811 relating to Etherley, Railey Fell, North Bitchburn and Brusselton Collieries involving Richard Peirse, his son and heir Richard William Christopher Peirse and John Flintoff. Other names mentioned are William Stobart and John Smith (both viewers) and George Dixon from Cockfield.

Above: Details of Accounts 1782-1810 from the legal agreements for Etherley, Railey Fell, Bitchburn & Brusselton Collieries[10]

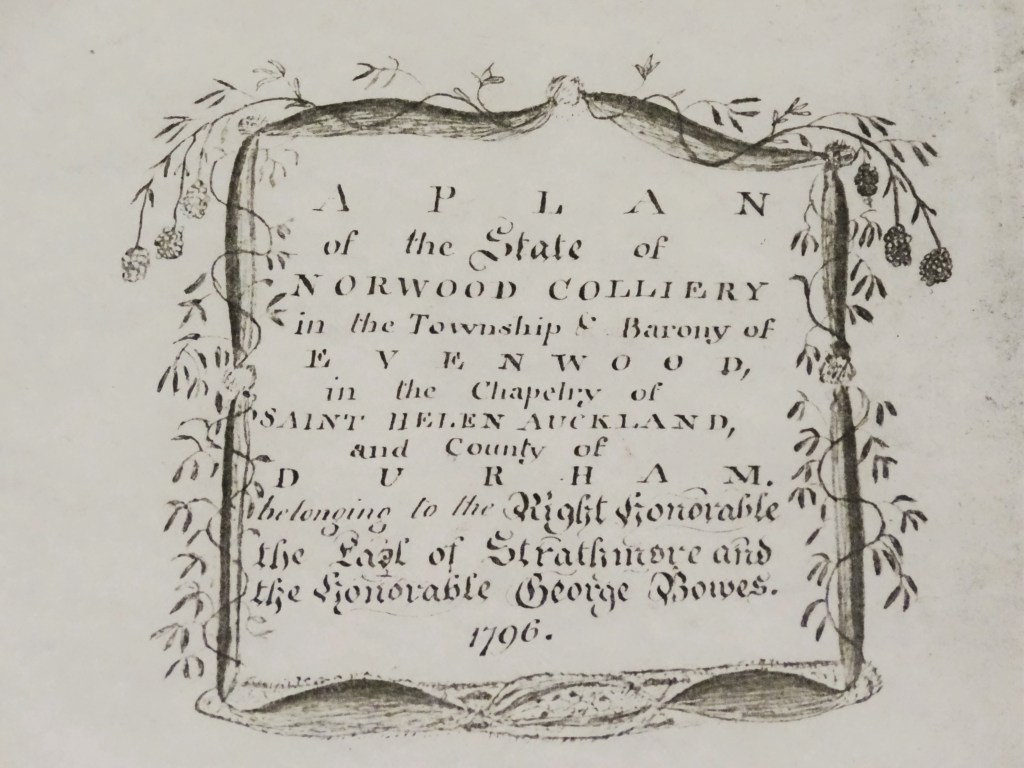

1796: Norwood Colliery was worked by Messrs George and John Dixon and John Flintoff on land owned by the Earl of Strathmore. There were a number of pits and drift mines including Lane Side Pit, East Field Pit, Quick Hedge Pit, Dyke Pit. There were two roads leading to the colliery, one from Butterknowle Lane and one from Evenwood Bridge known as Norwood Lane. There must have been plenty of coal traffic to warrant the construction of the substantial stone bridge which crosses the River Gaunless between well-established village of Evenwood to the south and the farming area to the north, dominated by the imposing Ramshaw Hall.

Above: 1796: Title Block for the Plan showing Norwood Colliery[11]

WHAT COULD HAVE BEEN

Canals were developed in almost in every other region of England but the North East. Waggon ways were the preferred mode of transport in Durham and Northumberland to carry coal from the collieries and pits to the staithes on the rivers Tyne and Wear thenceforth via keels, (barges) and colliers to London, the Low Countries and beyond.

If this canal scheme had been implemented, the landscape of south west Durham would have been totally different from today. The major transport elements would have been:

- The main canal with associated locks and dock basins from Stockton to Darlington to Killerby to Staindrop to Winston, along land to the north of the River Tees.

- The two feeder canals with associated locks from the collieries to the ridgeline from Brusselton to Bolam to Keverstone to Shotton, to sites at Keverstone Grange at the top of Keverstone Bank and Quarry House, east of Morton Tinmouth.

- The terminus of the two feeder canals at Keverstone Grange and Quarry House, Morton Tinmouth would have become major coal depots. Narrowboats or barges, pulled by horses along the tow paths, would have been emptied into coal yards. Coal and possibly coke waggons would have been loaded up for the decent down the waggon way inclines to depots near Carr House, east of Staindrop and Kiln Lane, north west of Killerby.

- Alternatively, at the Staindrop and Killerby, it is possible that there would have been timber staithes by the canal, along which the loaded coal waggons would run and then be emptied into vessels below.

Canal dock basins with extensive wharfs are found throughout England, particularly in central London and the West Midlands and perhaps the Staindrop and Killerby facilities would have developed on a similar scale.

Above: c.1830, a coal staith to the west of the Ouseburn which served a pit at Shieldfield, Newcastle-upon-Tyne (engraving by Carmichael)

The Chesterfield Canal opened in 1777 [12]

The proposed south west Durham canal system could have been similar to the Chesterfield Canal. It was built between 1771 and 1777 and ran for 46 miles from the River Trent at West Stockwith, Nottinghamshire to Chesterfield, Derbyshire. It was designed by James Brindley and built primarily for transporting coal from local collieries to markets around the River Trent and lead from mines in Derbyshire for export. Railways, including one of the earliest in Derbyshire, opened in 1789, and tramways brought coal and lead to the canal wharfs for loading into the narrowboats.

A unique type of narrow-keeled, wooden boat, locally called, “cuckoos” was developed for use on the Chesterfield Canal. The cabin was below deck and the barge could support a mast and sail. Barges on the main canal were around 70 feet long by 7 feet wide and held approx. 20 tons. Smaller boats, 21 feet long by 3½ feet wide were used on feeder canals. Coal was transhipped from the smaller to larger barges using cranes at the canal wharfs.

Stourbridge Canal Basin, Worcestershire

Bugsworth Canal Basin, Derbyshire

Above: Foxton Locks, Leicestershire

WAGGON WAYS

Two waggon ways were proposed, one commencing at Keverstone Grange and the second from near Quarry House, west of Morton Tinmouth. Both were located on the higher ground along the ridgeline from Bildershaw – Bolam – Keverstone – Shotton which separates the rolling countryside of the Great Northern Coalfield to the north from the fertile agricultural River Tees valley and plain to the south. The Keverstone waggon way terminated near Carr House, east of Staindrop and the Quarry House waggon way terminated at Kiln Lane, near Killerby.

Keverstone Grange and Quarry House would have been the two sites for the main coal collection points from the collieries. Horse drawn narrowboats or barges would have been emptied and the coal loaded into chauldrons which would have been sent down the waggon way to the canal wharfs or staithes at Staindrop and Killerby.

It is possible that these two sites may have developed into major dock basins and canal wharfs similar to those elsewhere in England.

Above: A chauldron, surviving at the Bowes Railway

The two waggon ways [13] may have followed the principle of the stationary hauling engines used on the Brusselton and Etherley inclines on the Stockton and Darlington Railway or another of George Stephenson’s schemes, the Bowes Railway at Springwell, to the north of County Durham. A local example of a colliery incline was that used at Randolph Colliery, Evenwood.

The Bowes Railway

Built about 1826 by George Stephenson at Springwell – photographs below show some of the features. This railway provided the waggon way link between Monk Moor pit at Black Fell and other coal mines in north west Durham across the Team Valley to the coal staith at Jarrow on the south bank of the River Tyne, where the coal was loaded into sea-going ships, colliers. After several extensions, its total length in 1855 was 24km (about 15 miles). Its central section, about 8 km (about 6 miles) in length consisted on two rope-worked incline planes crossing the valley of the River Team. Over the years, the railway was extended westwards to other collieries and as new pits opened up, they were connected to the system. In full, the line ran from collieries at Dipton, Burnopfield, Byermoor, Wardley, Andrews House then joined up to Marley Hill, Kibblesworth and up to Mount Moor, Vale Pit via the Blackfell incline and onto Springwell Colliery using the Blackham’s Hill Engine then down to Wardley Colliery No.2, Follonsby Colliery and Monkton Coke Works via the Springwell Incline to coal staithes at Jarrow on the River Tyne. [14]

The central features were the Blackfell Incline, Blackham’s Hill West and East inclines, which are operated by a stationary engine[15] and the Springwell Incline. Two hilly sections of the Bowes Railway used gravity to move wagons along the track. Wagons full of coal at the top of the slope were connected to empty wagons at the bottom by a rope, which then ran around a return wheel. As the loaded wagons rolled down the hill they pulled the empty wagons to the top. Where the gravity haul method was unsuitable, some sections of the line were operated by a stationary steam engine.[16]

Above: 2021 A Bowes Railway wagon

Above: The return wheel

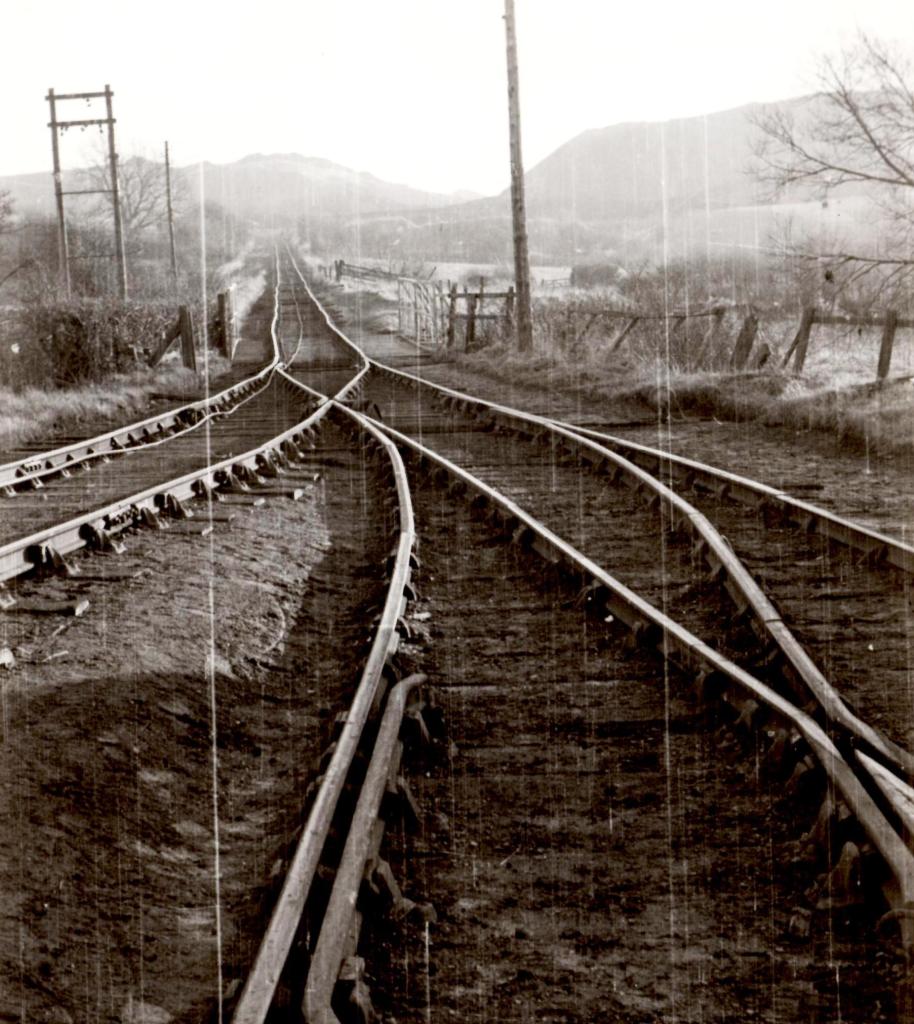

Above: The Springwell Incline looking eastwards towards Jarrow.

Above: 2021: A similar view

At its peak, it handled over 1M tons of coal per year. It remained virtually intact until 1968. It is now preserved and it is the world’s only working standard gauge rope hauled railway.

Randolph Colliery Incline, Evenwood

It operated between about 1894 and 1968 and connected the colliery with the Haggerleases Branch railway below in the valley of the River Gaunless. It was a self-acting incline 120 yards in length, worked by a stationary engine, taking coal and coke wagons down to the railway.[17]

Above: The Engine House at the top of the bank.

Above: Looking north, down to the Haggerleases Branch railway, as the incline crossed the bridge over Copeland Road.

Above: Looking south and up the bankside to Randolph Colliery.

TRAM ROAD OR RAILWAYS

In 1825, the world famous Stockton and Darlington Railway designed by George Stephenson, was the scheme which successfully connected the Auckland Coalfield to the port at Stockton-on-Tees. Witton Park Colliery was linked via the Etherley and Brusselton Inclines to the railway at Shildon then onto Darlington and Stockton. The Black Boy Pit at Auckland Park was connected by another branch line and in 1830, the Haggerleases Branch was opened which meant coal from Norwood Colliery and pits at Butterknowle and Copley could be exported more widely.

Prior to this, the following schemes were proposed:[18]

- 1810: Prompted by Tees Navigation Company’s improvement scheme which eliminated a large meandering loop in the River Tees, known as the, “New Cut” making Stockton a deep sea port, local businessmen proposed that a committee be set up to examine the practicability of building a railway or canal from Stockton to the coalfields.

- 1812: Darlington industrialists decided to engage John Rennie, an eminent engineer, to examine the merits of a canal or railway. Published in 1813, the report recommended a canal, similar to that proposed by Brindley 42 years earlier. The estimated cost was £95,000 for the Stockton to Darlington section and together with the branches, the total cost was £205,618. It failed to gain support.

- 1818: Business interests from Darlington and Stockton commissioned another report. The Stockton men favoured a canal from Portrack via Bradbury to Evenwood Bridge. John Rennie was engaged again and with the services of George Overton, a Welsh engineer, published their findings 20 October 1818. A railway was recommended at an estimated cost of £124,000 but this proved too expensive.

- 1818: The Stockton men had a scheme drawn up by Christopher Tennant and his surveyor George Leather for a canal between Portrack and Evenwood Bridge with an estimated cost of £205,283 but it gained little support.

- 1819: Following the formation of a Railway Company, Robert Stevenson was instructed to conduct another survey and draw up a Bill for Parliamentary approval. The proposed route attracted opposition including the 3rd Earl of Darlington (William Harry Vane 1766-1842, created the 1st Duke of Cleveland in 1833). [19] Apparently, the preferred line was close to one of the Earl’s fox coverts.

- 1820: Edward Pease looked again at the Overton plan and revised the route to include branches to Evenwood Lane, Coundon Grange and Yarm. The proposed plan for an, “Intended Tram Road from Stockton by Darlington” [20] was thwarted by the death of King George III which resulted in Parliament being dissolved.

1821: A third Bill was drawn up and this included further revisions to Overton’s plan with extensions to Coundon and along the wharf at Stockton. The proposal for, “The making of a railway or tramroad from the River Tees at Stockton to Railey Fell, with three branches therefrom terminating at or near Yarm Bridge, Piercebridge and Howlish Lane, all in the County of Durham” was successful. It received Royal Assent 19th April 1821.

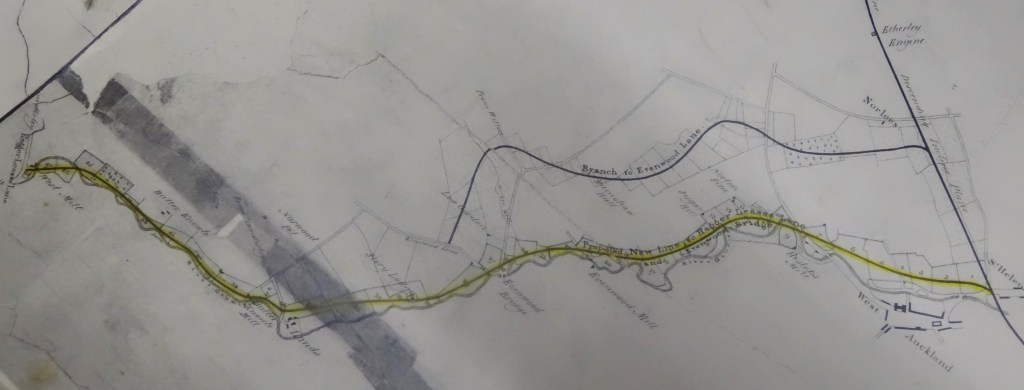

1823: With specific reference to the Haggerleases Branch, a plan deposited to John Dunn, the Deputy Clerk of the Peace for the County of Durham on the 7th September 1823 was surveyed by John Dixon. He was the grandson of George Dixon (1713-1785) who was associated with Brindley’s canal.[21] Robert Stephenson, son of George, was the Engineer.[22] This plan shows the old branch line from Norlees to Evenwood Lane (the Overton line) and the proposed new route to Haggerleases Lane which followed the River Gaunless, along the valley.

Above: 1823: The Route of the Haggerleases Branch

This plan enjoyed the title:

“A plan of the railway or tramroad from the River Tees at Stockton to Witton Park Colliery and the several branches therefrom all in the County of Durham respectively authorised to be made by two several Acts of Parliament passed in the 2nd and 4th years of the reign of his present Majesty King Geo. IVth and also a plan and sections of several new or additional branch railways or tramroads proposed to be made from the said main railway.”

On 17th May 1824, an Act of Parliament was obtained to permit this route and relinquished the Evenwood Lane line.[23] It was constructed and was known as the Haggerleases Branch between 1830 and 1899. John Dixon was George Stephenson’s principle assistant and was responsible for much of the detailed work.[24] After 1899, the Branch was renamed the Butterknowle Branch. Most of the railway was closed in 1963. Part survived until 1968, when the Tunnel Junction to Evenwood section was closed due to the closure of Randolph Coke Works and the abandonment of the Randolph Incline.

POSSIBLE URBAN DEVELOPMENT: THIS IS SHEER SPECULATON

It is not beyond the realms of possibility that a town could have been established somewhere to the north of the River Tees between Killerby, Ingleton and Morton Tinmouth. A second community could have developed on land east of Staindrop. Perhaps Bishop Auckland and Shildon might not have developed as they did, had these canal schemes taken place.

Around the transport hubs associated with the proposed canal system at Carr House, Staindrop and Kiln Lane, Killerby commercial development would have flourished – waggon way coal yards, staithes, canal wharfs and dock basins, plus other commercial enterprises such as repair shops for waggons and barges, stables and livery for horses, blacksmiths, merchants for the delivery and sale of hay and fodder, depots for land sale of coal and coke, boarding houses and houses for workers, social infrastructure such as public houses, shops, possibly chapels and so on.

Much of the land belonged to the 2nd Earl of Darlington and back in 1770, he was not convinced by Dixon’s plans. The scheme did not progress. Other proposals were submitted and eventually, 55 years later, George Stephenson provided the plan which persuaded others to invest. And the rest, as they say, is history.

REFERENCES

[1] A plan dated 1753 shows the Railey Fell boundary (surveyed by Richard Richardson) and grounds adjoining at West Auckland dated 1754 (surveyed by John Dixon). Halmote Collection.

[2] “History of Britain in Maps” 2017 Philip Parker includes a map with an excellent detail of the 1768 Stockton – Darlington – Winston proposed canal.

[3] 1768: A Detail from Armstrong’s Map of County Durham

[4] “Raby Castle official guide book” 2025 R.I. Smith p.70

[5] Raby Estates Archive Plan Ref: SR733/5 A Plan of the Intended Branch Canal from the Main Canal near Killerby to the Collieries. Undated but thought to be 1769-1770. Attributed to Jeremiah Dixon.

[6] “Raby Castle: official guidebook” 2025 R.I. Smith p.71

[7] Information taken from “The Report of Messrs. Brindley and Whitworth, Engineers concerning the practibility and expence of making a navigable canal from Stockton by Darlington to Winston in the County of Durham with a plan of the country, River Tees and of the intended canal Surveyed and made by Order of the Committee of Subscribers 19 July 1769. Newcastle, Printed by T. Slack 1770. Courtesy of Raby Estates Archives

[8] “Stockton and Darlington Railway 1825-1975” 1975 P.J. Holmes p.1

[9] See ref. 5 above

[10] Courtesy of John Stubbs

[11] Strathmore Papers ref:

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chesterfield_Canal#:~:text=The%20Chesterfield%20Canal%20is%20a,Date%20closed

[13] The old spelling had double G – waggon rather than wagon as spelt today.

[14] https://www.erih.net/i-want-to-go-there/site/the-bowes-railway

[15] https://www.nationaltransporttrust.org.uk/heritage-sites/heritage-detail/bowes-railway

[16] The Bowes Railway information panel

[17] https://evenwoodramshawdistricthistorysociety.uk/randolph-incline/

[18] Stockton and Darlington Railway 1825-1975” 1975 P.J. Holmes p.1-4

[19] “Raby Castle: official guidebook” 2025 R.I. Smith p.69

[20] Raby Estates Archives SR 142

[21] Holmes p.7

[22] Durham Record Office Ref QDP.9

[23] Holmes p.10

[24] Holmes p.9